View Winners →

View Winners →

A 320-year-old Japanese Heritage Shōya House from Marugame, Japan, has been carefully and meticulously disassembled and restored then shipped to The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. Sited on a two-acre lot at the storied Japanese Garden, this remarkable architectural and cultural gem will open to the public on Oct. 21, 2023.

During the Edo or Tokugawa period in Japan – between 1603 and 1867 – a single government ruled under a feudal system. It was marked by a flourishing economy and peaceful times. Samurai warriors, who were no longer necessary to protect their villages, moved to the cities to become artists, teachers, or shōya.

Successive generations of the Yokoi family served as the shōya of a small farming community near Marugame, a city in Japan’s Kagawa prefecture. Acting as an intermediary between the government and the farmers, shōya’s duties included storing the village’s rice yield, collecting taxes, maintaining census records, and documenting town life, as well as settling disputes and enforcing the law. He also ensured that the lands remained productive by preserving seeds and organizing the planting and harvesting. The residence functioned as the local town hall and village square.

In 2016, Los Angeles residents Yohko and Akira Yokoi offered their historic family home to The Huntington. Representatives of the institution made numerous visits to the structure in Marugame and participated in study sessions with architects in Japan before developing a strategy for moving the house and reconstructing it at The Huntington.

The Huntington raised over $10 million through private donations to accomplish the project. Since 2019, artisans from Japan have been working alongside local architects, engineers, and construction workers to assemble the structures and re-create the traditional wood and stonework features, as well as the roof tiles and plaster work, prioritizing the traditions of Japanese carpentry, artisanship, and sensitivity to materials.

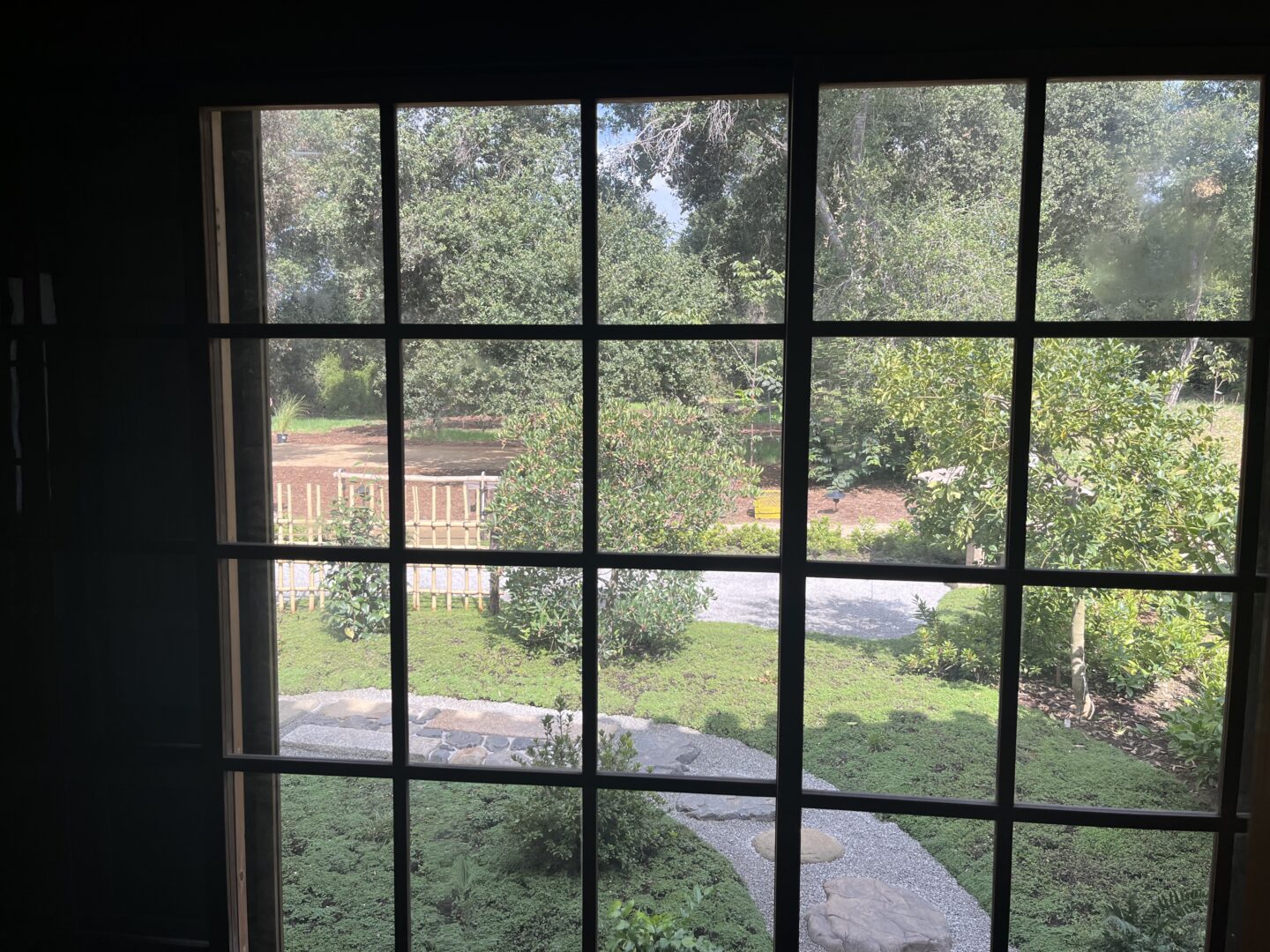

Visitors to The Huntington will get to see the Japanese Heritage Shōya House, a 3,000-square-foot residence built around 1700. A remarkable example of sustainable living, the compound consists of a small garden with a pond, an irrigation canal, agricultural plots, and other elements that closely resemble the compound’s original setting.

Robert Hori, the gardens cultural director and programs director at The Huntington, generously gives me a tour of the shōya house while he talks about the project. He begins, “Visitors will first view the agricultural fields and the gatehouse. In much of Asia, rice was a staple food and farmers played a very important role. Here we have terraced rice fields on one side and a field growing a variety of crops on the other side. This will give the public a sense of the seasons, the lifestyle of the Edo period in Japan and what the pre-modern way of life was like.”

As we reach the gatehouse, Hori says, “This compound was open during the day for business and at night the gates were shut. The gate was built for events and also to protect the house from weather because Japan and much of Asia are susceptible to typhoons. The gatehouse was damaged in a typhoon in 1970 so this structure was not original to the house; it’s a replica based on existing models from the same period in Japan and photographs.

“Inside the gatehouse is a dirt courtyard used for several purposes including drying the crops and where community gatherings – like harvest festivals – might have taken place. The house has two entryways. The formal entrance on the left has sliding panels, and was originally for samurai, dignitaries, and government representatives. Inside the main house, visitors will first see the front rooms, which were used for official functions. The doorway on the right, which Huntington visitors will use, was the everyday entrance for farmers and craftspeople. It has stamped earth floor. The front area consists of public rooms where business was conducted, and the back are the private quarters.”

Visitors entering the public rooms can watch a video that shows the disassembly and relocation of the house and its integration with the surroundings at The Huntington. Additionally, visitors will be able to learn about the traditional skills and tools of Japanese carpentry, such as the wood joinery that was used in constructing the house.

Hori continues, “I was part of the team that went to Japan in 2016 to look at the house to see if we could move it, how we were going to do it, and what changes had to be made to it so it could be approved. I was there again for part of the process of taking down the house but not for the entire nine months it took to disassemble it. The crew that took it apart inspected each part for any damage, cleaned, and repaired them. The house arrived at The Huntington in January of 2020.

“Everything in the house uses traditional joinery techniques. We had several crews of carpenters, plasterers, roofers, and tilers who came from Japan to work on it. It was a two-year process which was hampered by the pandemic in March of that year. It was difficult to get people to travel so there were periods when people went back and they had to quarantine and that really slowed things down. Additionally, there weren’t that many flights.”

A large clay wood fire cooking stove is the first thing visitors will see. Hori speculates that it used to cook perhaps as much as 60 cups of rice to feed the people working in the house and also during planting and harvest. These community efforts were spread out over several weeks.

In the kitchen area is a brick stove. Hori says, “We couldn’t move the one original to the house but this is the type of stove they had. The source of water for the kitchen is a well located just outside and there’s a sliding door you can open to access it.”

We then move to the private rooms and we take off our shoes. Hori describes, “This lower level was part of the kitchen which was the center of activity. It was probably where they dried and salted vegetables that would last the whole year. The upper level has a floor covering called tatami, mats that measure three-by-six feet. This was the family’s day room where they conducted their activities – they would eat their meals here, then they would use it as a work space after they put away their dishes. Japanese houses like this didn’t have central heating so everyone stayed close together near the fire.”

As we reach another area, Hori describes, “This was probably where they slept. It would have cabinets with futons or bedrolls, and sliding doors could close off the area at night.”

In the back is the master’s room. It has a display alcove called a tokonoma where a painting, a scroll, or a flower arrangement can be hung. There’s also a door that opens out into a small private garden.

We then go into the public spaces for dignitaries and the first room we enter has two shrines – one is Shinto and the other next to it is Buddhist. Explains Hori, “They had two religious systems that co-existed and people were both Shinto and Buddhist. Everything in Shinto is considered having a spirit; they worship mountain or forest gods. Buddhism, on the other hand, goes back over 2,500 years and started in India; it spread to China, and then to Japan. Buddhism also has a cultural and writing component from China that includes language and Chinese characters. The Japanese had their own language; they had a word for mountain, which is ‘yama’ like Fujiyama. The approximation in Chinese for mountain is ‘shan’ or ‘san.’ The same concept applies to religion – they have a cosmic god and a Japanese god.”

The main room where distinguished guests were received has a tokonoma on the side; it’s similar to the one in the master’s accommodations. A shoji opens to reveal a beautiful formal garden planted with carefully shaped pines and camellias, as well as cycads – considered a symbol of luxury in 18th-century Japan. The rocks in the garden came directly from the original property and were placed in the exact same spots in relation to the house, and a koi pond.

I ask what the condition of the house was when they went to Japan to look at it and Hori replies, “The last time it was rebuilt was in the 19th century around 1860 to 1870. It had also been modernized later – they put in electricity and flush toilets. But it hadn’t been lived in for over 30 years; the last person who resided there was the grandmother who passed away in the 1980s. And when a house is unoccupied, several things fall unto disrepair.”

About what challenges they faced after the house arrived here, Hori says, “Our first challenge was how could we construct the house so it passes the building code? We also have earthquakes in California so we had to build it to meet seismic requirements. We’d never done this before so we didn’t know if it was a viable undertaking. And, as far as I know, this is the first house of this size to be built at a public institution. This is the first Japanese house of this age and size in the United States.”

Standard houses in Japan are not this size, clarifies Hori. “Because of their responsibility, the shōya would have bigger dwellings with more amenities. A regular residence wouldn’t have this public area. The typical layout of an ordinary person’s house would have a kitchen, a dayroom/living room/dining room and a sleeping room. If you lived in the city your house might be twelve-by-twelve-square-feet. You ate, worked, and slept in the same room – something we call a studio.”

The house and the area surrounding it are models of sustainable living. Hori declares, “They probably didn’t have the word for sustainability but they had the practice in place. If they didn’t lead sustainable life styles, they wouldn’t be alive – it was a matter of survival. The keys to sustainability are reducing waste, reusing, recycling, and repairing. For example, these glass doors don’t line up exactly because they come from different parts of the house. They have been repaired and reused, thus reducing waste.”

“Growing your own food is an example of a sustainable life style,” adds Hori. “Since we are a botanical garden, we tell everyone that farming is the root of ornamental landscapes because it has to do with being able to move earth and control water. In the other gardens – the Chinese Garden or the Japanese Garden – we have ponds and streams, and they’re all part of an irrigation system.”

As we walk to the back of the house Hori shows me a covered circular ground container and says, “Thinking about how we treat waste, we recreated a pit toilet. There’s a real lavatory inside, but having this type of toilet is one of the keys to sustainability – reducing waste. In Japan, China, and much of Asia, they use human waste for fertilizer.”

Hori also discloses that there were two storehouses on the property – one for household items and the other for rice. They haven’t been built but they have the footprint of one of the storage houses.

“Construction of the irrigation canal is underway,” Hori explains when we walk by it. “Japan gets about 100 inches of water from the rain but even in countries with an abundance of water, you have to save the water, control the water, and use it for agriculture; this is part of the agricultural system. In Japan and other Asian countries, they use gravity – they have terraced paddies and fields to move water from the top to the bottom. Using natural forces instead of electricity or a pump is conserving resources.”

“What we’re recreating here is a village – a community,” Hori pronounces. “It is looking at another culture and how people in the past addressed sustainability. And it’s one of the biggest global problems we face today.”

The Yokois made a well-considered decision to endow their shōya house to The Huntington, an institution renowned for preserving historical artifacts and cultural treasures. Under its stewardship, this remnant of history will be protected for centuries to come.

And The Huntington has taken this responsibility a step further by restoring the shōya house and its surroundings to educate us and demonstrate that it’s possible to live sustainably. It’s a lesson we have to heed and practice to help save our planet and ensure not only our survival but also that of future generations.