View Winners →

View Winners →

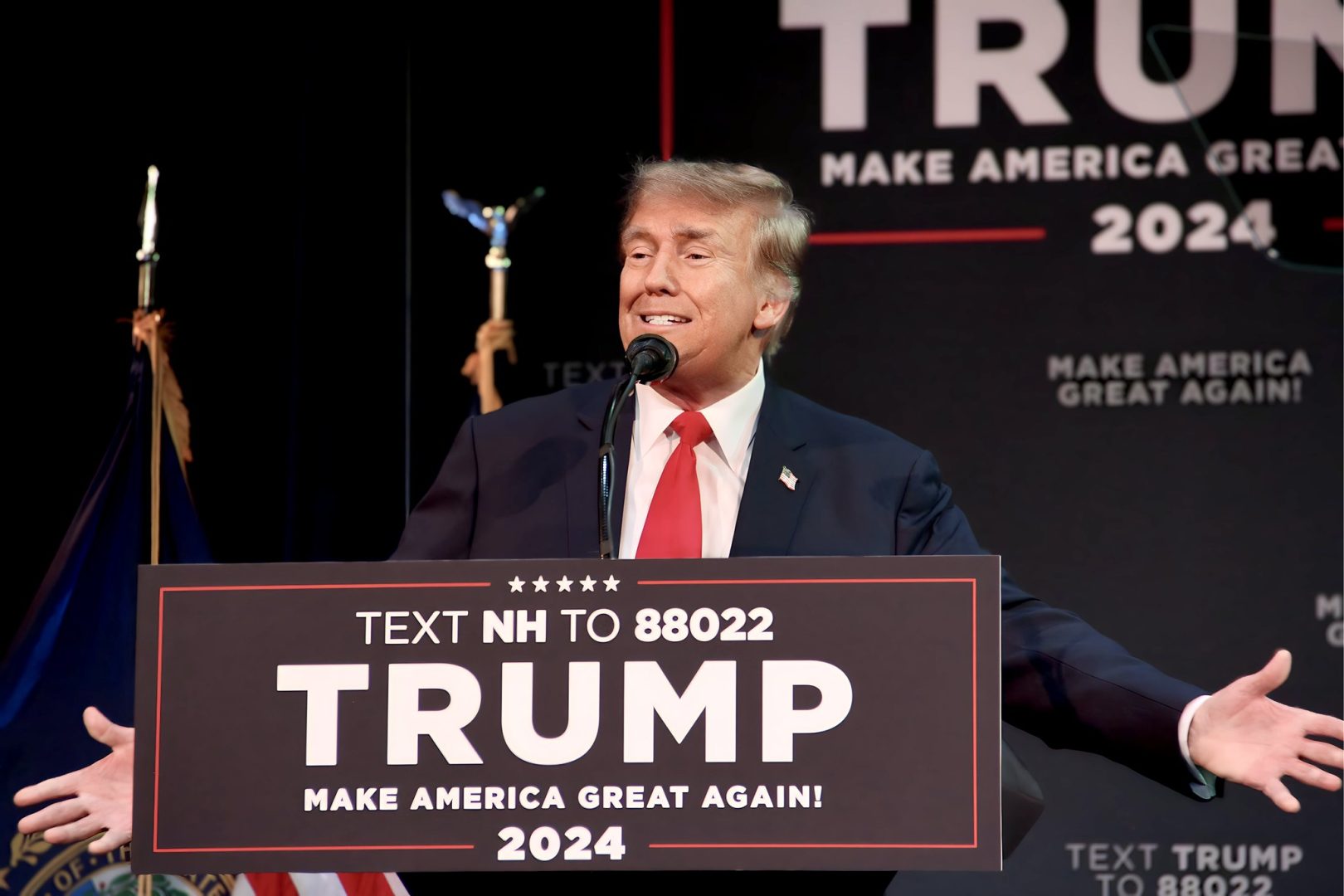

Former President Donald Trump holds campaign rally at the Rochester Opera House in Rochester, New Hampshire, on Sunday, Jan. 21, 2024. | Photo by Liam Enea CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

By Robert Faturechi, Justin Elliott and Alex Mierjeski

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Former President Donald Trump scored a victory last month when a New York court slashed the amount he had to put up while appealing his civil fraud case to $175 million.

His lawyers had told the appellate court it was a “practical impossibility” to get a bond for the full amount of the lower court’s judgment, $464 million. All of the 30 or so firms Trump had approached balked, either refusing to take the risk or not wanting to accept real estate as collateral, they said. That made raising the full amount “an impossible bond requirement.”

But before the judges ruled, the impossible became possible: A billionaire lender approached Trump about providing a bond for the full amount.

The lawyers never filed paperwork alerting the appeals court. That failure may have violated ethics rules, legal experts say.

In an interview with ProPublica, billionaire California financier Don Hankey said he reached out to Trump’s camp several days before the bond was lowered, expressing willingness to offer the full amount and to use real estate as collateral.

“I saw that they were rejected by everyone and I said, ‘Gee, that doesn’t seem like a difficult bond to post,’” Hankey said.

As negotiations between Hankey and Trump’s representatives were underway, the appellate court ruled in Trump’s favor, lowering the bond to $175 million. The court did not give an explanation for its ruling.

Hankey ended up giving Trump a bond for the lowered amount.

It’s unclear if Trump lawyer Alina Habba or the rest of his legal team were made aware that Hankey reached out about a deal for the full amount. Trump’s legal team did not respond to requests for comment.

After ProPublica reached out to Trump’s representatives, Hankey called back and revised his account. He said he had heard “indirectly” about ProPublica’s subsequent inquiries to Trump’s lawyers. In the second conversation, he said that accepting the real estate as collateral would have been complicated and that he wouldn’t have been able to “commit” to providing a bond in the full amount “until I evaluate the assets.”

Legal ethics experts said it would be troubling if Trump’s lawyers knew about Hankey’s approach and failed to notify the court.

New York state’s rules of professional conduct for lawyers forbid attorneys from knowingly making false statements to a court. At the time Trump’s lawyers told the court that meeting the bond would be impossible, Hankey said he had not yet reached out to the Trump team.

But the rules of conduct also dictate that lawyers must “correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made” to the court.

“If that deal was on the table for the taking, the representation from the earlier time would be untrue, and the lawyer would have an obligation to correct,” said Stephen Gillers, a legal ethics professor at New York University Law School.

In the rules of conduct for lawyers, the failure to update an important piece of evidence would fall under what’s referred to as the “duty of candor to a tribunal,” said Ellen Yaroshefsky, a professor of legal ethics at Hofstra Law.

“Any judge is going to be furious that this wasn’t corrected,” she said.

Scott Cummings, a legal ethics professor at UCLA’s law school, agreed that there was a potential ethical failure but said Trump’s lawyers could argue that they were not obligated to alert the court.

“A very narrow reading of this rule would be there is no obligation to report because it wasn’t a false statement at the time,” Cummings said.

The need for the bond arose from a case brought against Trump by the New York attorney general, who accused him of fraudulently inflating his net worth to get favorable loans and other benefits. A judge agreed and ordered Trump and the other defendants to pay $464 million.

Trump had a month to come up with the sum or risked having his properties seized.

When a defendant loses a civil case in New York, the creditor — in this case the attorney general — can immediately go after the defendant’s assets to collect the judgment. The defendant can protect his assets while pursuing an appeal by posting a bond. Typically obtained from an insurance company for a fee, the bond is essentially a promise that the company will guarantee payment of the judgment if the appeal fails.

In his first interview with ProPublica, Hankey said that when he heard Trump was having trouble getting a bond, he reached out to Trump’s camp, several days before the bond was reduced, with an offer to help.

Hankey, who took a break from a game of bocce to speak to ProPublica, is rated by Forbes as one of the 400 wealthiest people in the world with an estimated net worth of more than $7 billion. He made much of his fortune with high-interest car loans to risky borrowers, and he is chairman of a Los Angeles-based network of companies across a range of industries, including real estate, insurance and finance. He has said he supports Trump politically but would have wanted to make the deal no matter his politics.

Hankey told ProPublica that during the talks he came to the conclusion that Trump’s “got the liquidity” and was confused why others would have rejected him, speculating that some may have wanted to avoid political backlash: “If you’re a public company, maybe you don’t want to offend 45% of the population.”

Hankey said he informed Trump’s camp that he was willing to work with them, and “they said they had the collateral.” The two sides went over the assets that had to be pledged, and it was up to Trump “if they wanted to do it.” (In his second call, Hankey said making a deal would have been “difficult.”)

But, he said, the deal for the larger amount was dropped during a large Zoom call between the two sides, when Trump’s camp got a call informing them that the bond was reduced.

“They thanked us for trying to help: ‘Maybe next year, we’ll try to do business again,’” Hankey recalled them saying.

But several days later, Hankey said, they called back, hoping to make a deal for the reduced bond, and Hankey agreed.

The bond saga is not over. In a brief court filing last Thursday, the New York attorney general asked Trump or Hankey’s company to show that the company has the financial means to fulfill the $175 million bond.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox. Republished with Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).