View Winners →

View Winners →

USC Pacific Asia Museum (USC PAM) continues its mission and vision to further intercultural understanding through the arts of Asia and the Pacific Islands with “Imprinting in Time: Chinese Printmaking at the Beginning of a New Era.”

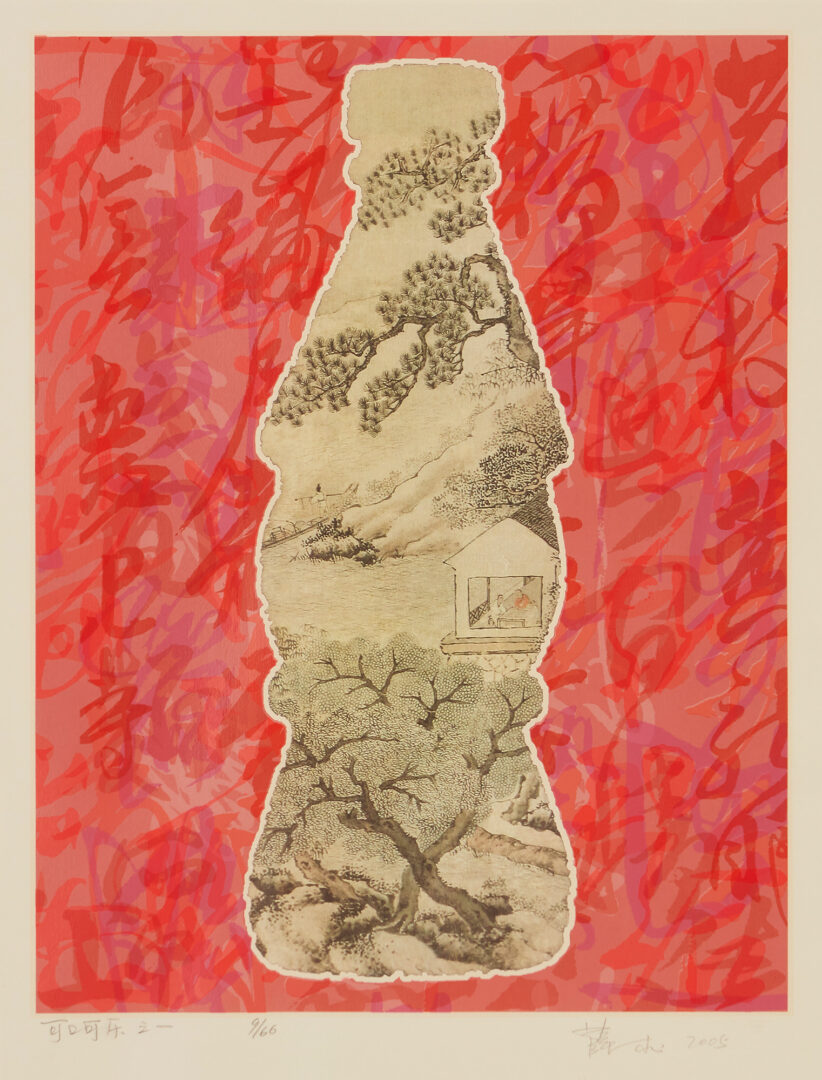

On view from Aug. 11 through Nov. 12, the exhibition looks at printmaking by Chinese artists from the 1980s to the present and analyzes the unique narrative of the medium within the contexts of cultural, academic, sociopolitical, and economic changes in recent Chinese history.

Imprinting in Time is curated by Danielle Shang, a Los Angeles-based art historian and exhibition organizer. Her research focuses on the impact of globalization, urban renewal, social change, and class restructuring on art-making and the narrative of art history.

Woodcut originated in China, dating as far back as the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to 220 A.D). The first woodblock fragments were of silk printed with flowers in three colors. Much later – in the early 20th century – it became a popular art form used by Chinese progressives to advocate for social change. The New Woodcut Movement hit its stride in China from 1912 through 1949.

In an article about the history of the movement (From New Woodcut to the No Name Group: Resistance, Medium and Message in 20th Century China) New York-based artist Chang Yuchen wrote that Lu Xun was probably the most significant among these activists. He established the Morning Flower Society in 1929, which published journals that introduced foreign literature and art to Chinese audiences. Two of the volumes were dedicated to modern woodcuts – considered by Lu Xun as the most accessible and efficient means for disseminating revolutionary ideas among the masses.

The Communist Party became a powerful force during the Sino-Japanese War and Mao Zedong exerted his authority. He delivered a famous speech at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Arts in May 1942, where he declared “Literature and art are subordinate to politics, but in their turn exert a great influence on politics” and quoted a poem by Lu Xun to support that view. Following his speech, progressive artists and writers moved to Yan’an to produce art that responded to Mao’s call. What began as a pursuit of communication, however, was reduced to serving as the Communist Party’s marketing tool.

In 1979, the Ministry of Culture restored the party memberships of artists who had been sent to labor camps and persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. One of these was Jiang Feng, who played a crucial role in the New Woodcut Movement. He was appointed director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and later as chairman of the reconstituted Chinese Artists Association.

Another suspected ‘rightist’ – Liu Xun – was released from incarceration and named head of the Beijing Municipal Artists Association. When he learned about the group of plein air painters – who later became known as the No Name Group – who managed to work under such impossible conditions, Liu Xun organized an official exhibition of their work. More than 2,700 people came to the show on the first day.

However, without the hostile conditions that kept them united in their art, the No Name Group slowly drifted apart. Some of them immigrated to other countries and some stopped painting altogether. Those who continued painting – and remained nameless – were resistant to the booming market for Chinese contemporary art just as they refused to go along with politics.

The emergence of etching, lithograph, silkscreen, and digital devices in the 1980s added new energy to the medium. Most artists included in USC PAM’s exhibition were academically trained printmakers; however, a few have established their reputations in other media and explored printmaking as an additional aesthetic in their practices.

Museum curator Rebecca Hall states, “Imprinting in Time is an exciting exhibition for USC Pacific Asia Museum to share with the public because all but a few of the artworks in the exhibition come from the museum’s permanent collection. Formed around the recently donated Charles T. Townley collection of contemporary Chinese art, Danielle Shang did an outstanding job of teasing out the strengths of the Townley collection and finding further artworks to supplement her thesis in PAM’s permanent collection, some of which have not been exhibited in many years.”

“Printmaking, particularly woodcut, is uniquely important in modern Chinese history because it was instrumental for disseminating ideologies of the nation-state to the masses from the 1930s to the 1980s,” says Shang. “It is a perfect example of hybridizing a traditional Chinese medium that has been around for centuries with modernist techniques from the West.”

The exhibition will show 60 works organized into three sections: the Modern Woodcut Movement; the Post Mao Era; and Crisis and Hope Since the 1990s.

Modern Woodcut Movement

Among all the printmaking techniques, the woodblock is most significant in modern Chinese history for articulating social commentary and nationalistic sentiments. The monumental figure who initiated the movement was not a visual artist but the writer, collector, and activist Lu Xun (1881-1936). In the early 1930s, Lu introduced Käthe Kollwitz’s woodcut to Chinese artists, who immediately embraced the medium for its effectiveness in engaging a broad public. These artists began to produce prints with simplified but highly suggestive forms and figures to depict the violence, injustice, and angst that plagued Chinese society.

After Mao Zedong’s speech at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art (1942), woodcut was given singular priority, and its subjects shifted from social critiques to celebrating the bright new life under Communist control. Subsequently, the woodcut printmaking that hybridized German Expressionism, Soviet Social Realism, Chinese traditional water-based printing techniques, and folk arts’ vernacular styles was established as a major discipline in all art schools and employed largely for propaganda purposes to serve the state after the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Post Mao Era

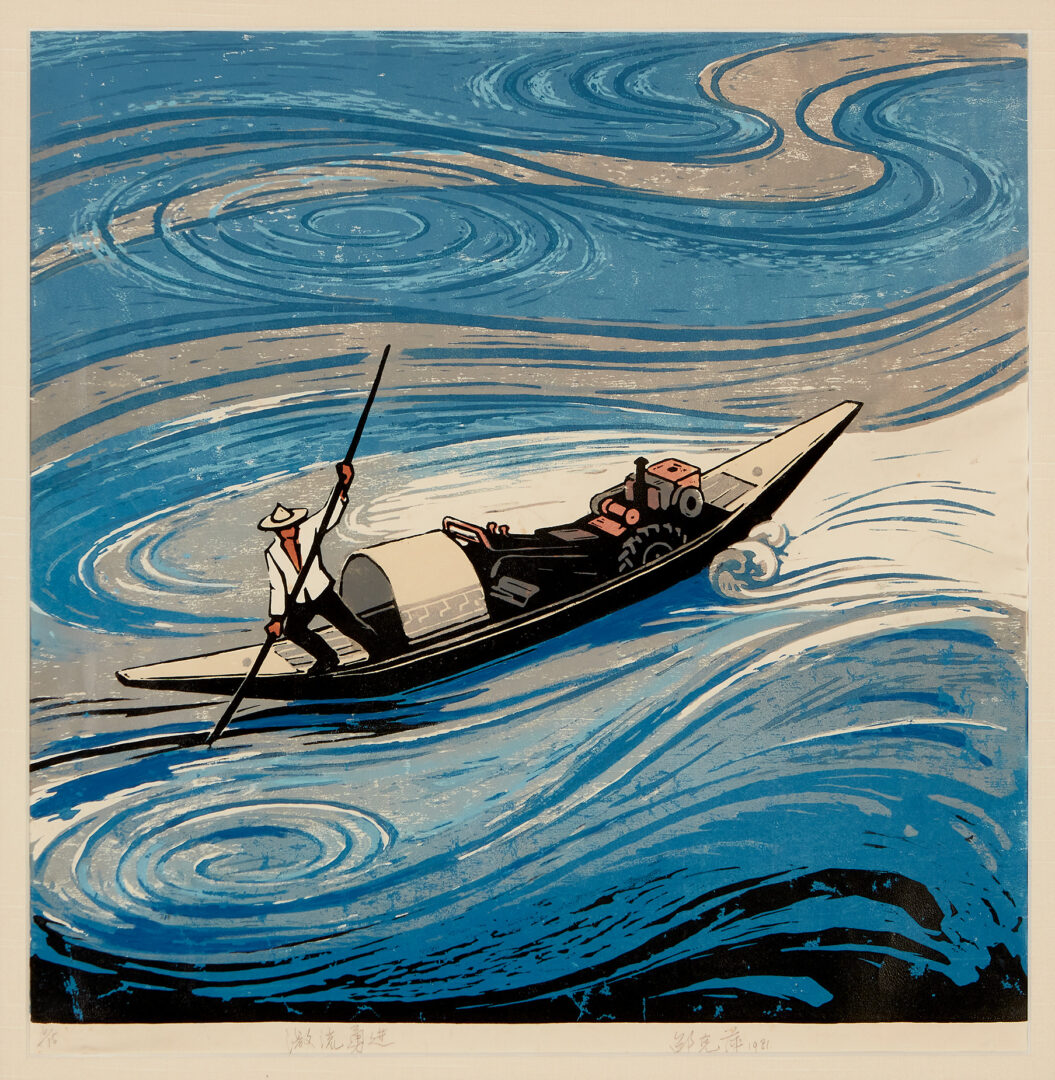

After 1976, while many artists continued to produce works that celebrated the socialist vision of modernity, others began to explore the notion of individuality and new graphic effects. The rise of etching, lithograph, silkscreen, and digital devices added new energy to the medium. Meanwhile, distinct regional schools emerged, notably the Great Northern Wilderness and the Yunnan School.

Contrary to earlier times when human figures and narrative themes dominated printed pictures, landscapes, and abstract compositions became popular. Some artists intentionally evoked the traditional Chinese ideal of integrating calligraphy, painting, and poetry when combining images with texts.

Shang expounds on the regional schools, the art style, and the artists who emerged during this period.

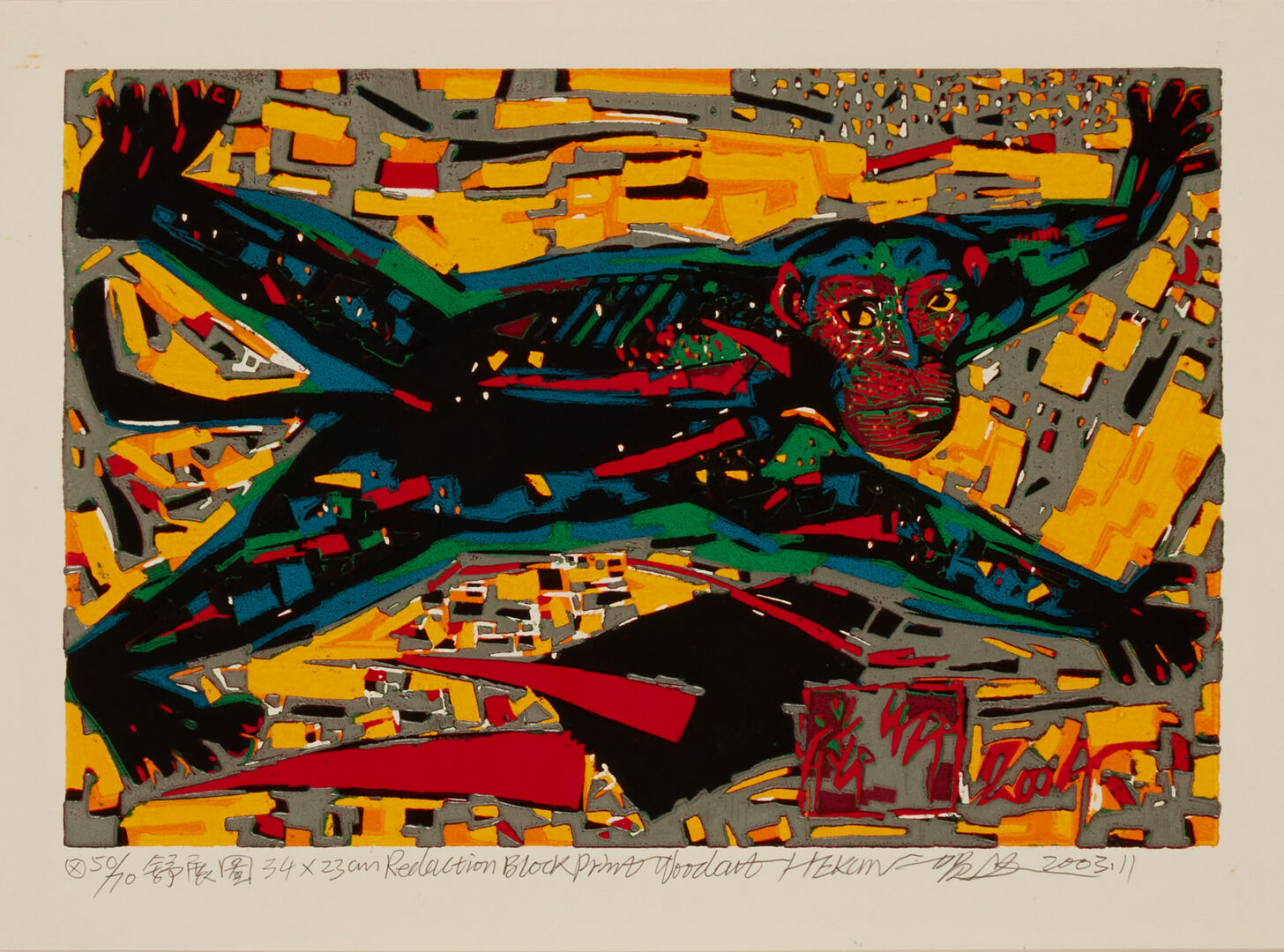

“Since the late 1970s, artists in Yunnan Province, including Zheng Xu and He Kun, turned their attention to local ethnic groups, neighboring Southeast Asian cultures and the ancient Chinese technique known as heavy color painting 工笔重彩画 that emphasizes line drawing and bold colors. Figures depicted by the Yunnan School artists are flat, geometric, semi-abstracted, and energized with bright colors, reminiscent of cubism and fauvism. Motifs incorporated into their works are derived not only from ancient Buddhist cave paintings but also from local traditional garments and decorations.”

“In the 1980s, Zheng and He among other printmakers in Yunnan began to create reduction woodcuts to produce heavy color prints,” Shang adds. “A color reduction woodcut is simply a relief print that is carved, inked, and printed multiple times using only one piece of woodblock. The entire edition must be printed at once since carving destroys the wood incrementally.

“The artists also established several workshops in the region to invite people from rural communities to make art, positioning printmaking at the intersections of arts practice, social engagement, and cultural restoration.”

Men were the dominant figures in this art form. Shang reveals, “Very few female artists were active in the history of Chinese printmaking. One extraordinary exception is Chen Haiyan (b. 1955, China), who, in her cycle of DREAM, developed a distinct style charged with raw, idiosyncratic, and expressive energy. The series narrates 20 of the artist’s dreams in monochrome woodcuts, integrating texts into images. The technique she employs to make the prints is known as touyin 透印 or ‘penetrating print.’ First, ink is rolled onto the wood block where a sheet of paper is smoothed on top. The next step is to burnish the paper with a spoon, rubbing until the ink soaks all the way through. Unlike other printing techniques, which create mirror images, touyin can be viewed from the front and the back – eliminating the need for the artist to make a preliminary, reversed design for carving. Thus, the artist’s ideas and emotions are conveyed directly to the woodblock without an intermediary step, affording her the spontaneity that attracts the viewer’s attention. She currently teaches at the China Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou.”

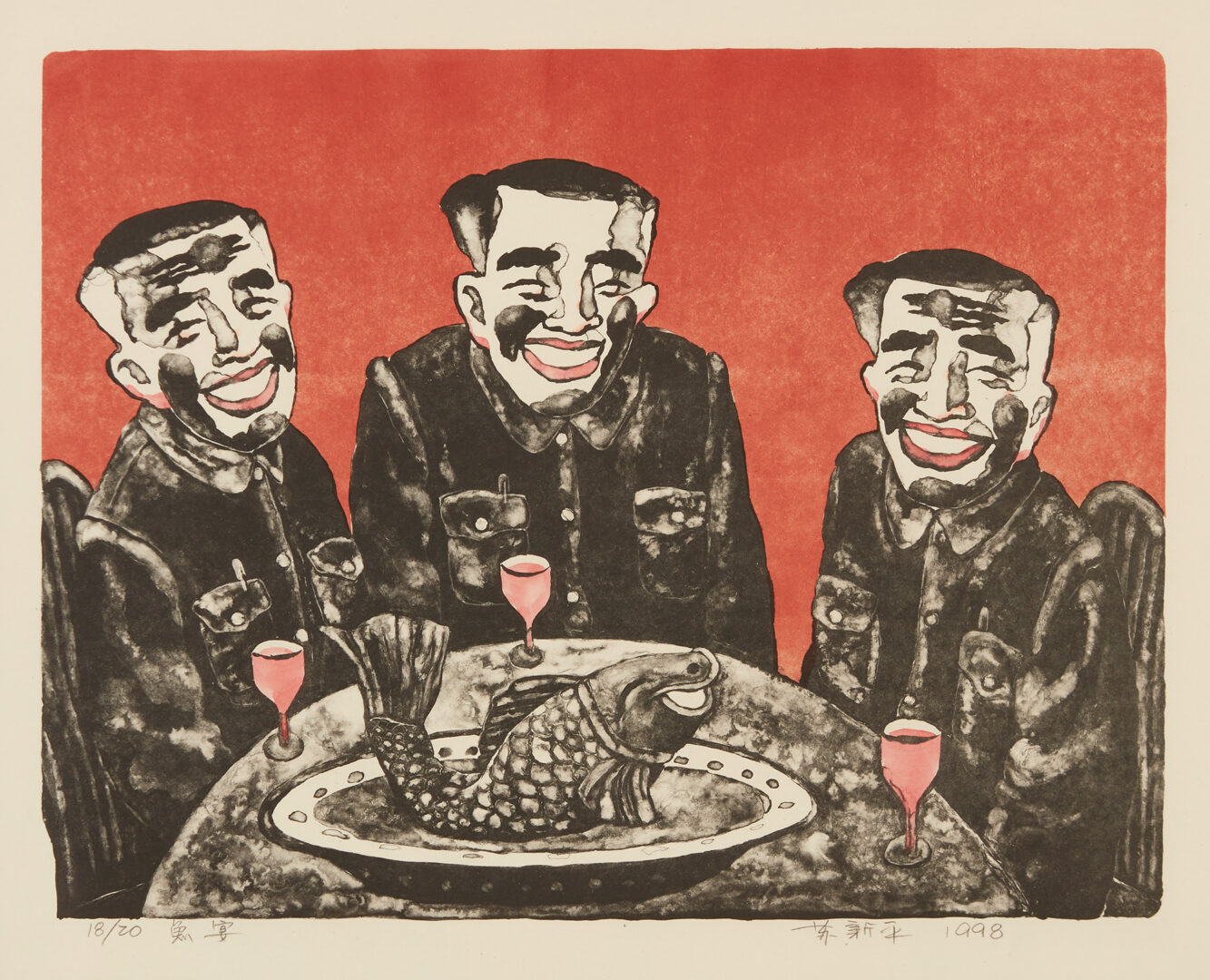

Crisis and Hope Since the 1990s

The 1990s saw China’s rapid transformation into a hyper-consumer society. As works of art entered the market as commodities, prints failed to gain recognition as valuable cultural products. To survive, printmakers had to switch to other media, teach, or hold positions at state-sponsored cultural organizations, whose programs continued instructing conservative subjects and styles. In response to the new conditions, a few artists have moved beyond technical concerns to search for ways to advance the medium and participate in global conversations. Their practices shine a new light on printmaking.

It’s unfortunate that despite its fascinating ancestry and storied past, printmaking in China did not continue to flourish. This exhibition at USC Pacific Asia Museum may yet demonstrate that prints – which have since been relegated to being disposable merchandise – and printmaking can be rejuvenated through a fresh audience. At the very least, it may engender a newfound appreciation for the art form.