View Winners →

View Winners → Bruce’s Beach bill passes state senate, advances to governor’s desk

|Photo courtesy of City of Manhattan Beach

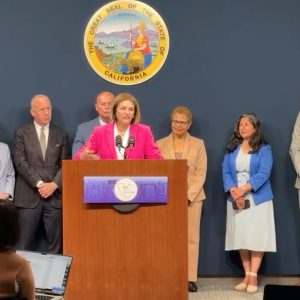

Proposed legislation that would help clear the way for the county to return a piece of Manhattan Beach coastline to the descendants of a Black family who had the land stripped away by the city nearly a century ago was awaiting the governor’s signature Friday.

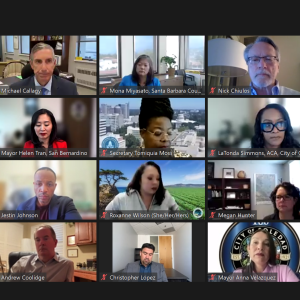

The state Senate on Thursday approved Senate Bill 796, which would authorize the county to return property known as Bruce’s Beach to the Bruce family.

“We are one step away from correcting a century’s old injustice,” the bill’s author, Sen. Steven Bradford, D-Gardena, said in a statement. “The vote we took today (Thursday) is proof that it is never too late to do the right thing. SB 796 is the embodiment of the truth that if you can inherit generational wealth in this country, then you can inherit generational debt too. The Bruces’ endured harassment, hostility and violence by the Ku Klux Klan before the city seized their land.”

County Supervisor Janice Hahn, who has spearheaded efforts locally to return the land to the Bruce family, hailed the passage of the bill.

“I have been so moved by the overwhelming support that we have gotten for this effort in Sacramento,” Hahn said in a statement. “At long last, this bill is heading to Governor (Gavin) Newsom’s desk. I not only urge him to sign it, but I also think it would mean so much if he signed it at Bruce’s Beach.”

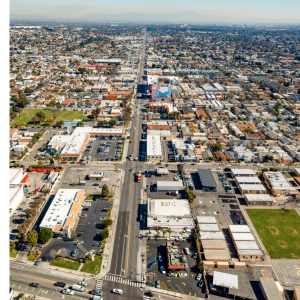

The public seizure of the Bruce’s Beach property has long stained the history of Manhattan Beach, particularly in the past year amid a nationwide reckoning on racial injustice.

Willa and Charles Bruce purchased land in 1912 for $1,225. They eventually added some other parcels and created a beach resort catering to Black residents, who had few options at the time for enjoying the California coast.

Complete with a bath house, dance hall and cafe, the resort attracted other Black families who purchased adjacent land and created what they hoped would be a ocean-view retreat.

But the resort quickly became a target of the area’s white populace, leading to acts of vandalism, attacks on vehicles of Black visitors and even a 1920 attack by the Ku Klux Klan.

The Bruces were undeterred and continued operating their small enclave, but under increasing pressure, the city moved to condemn their property and other surrounding parcels in 1924, seizing it through eminent domain under the pretense of planning to build a city park.

The resort was forced out of business, and the Bruces and other Black families ultimately lost their land in 1929.

The families sued, claiming they were the victims of a racially motivated removal campaign. The Bruces were eventually awarded some damages, as were other displaced families. But the Bruces were unable to reopen their resort anywhere else in town.

Despite the city claiming the land was needed for a city park, the property sat vacant for decades. It was not until 1960 that a park was built on a portion of the seized land, with city officials fearing the evicted families could take new legal action if the property wasn’t used for the purpose for which it was seized.

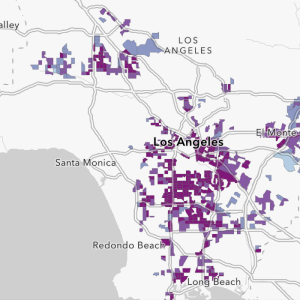

The exact parcel of land the Bruces owned was transferred to the state, and then to the county in 1995.

The city park that now sits on a portion of the land seized by the city has borne a variety of names over the years. But it was not until 2006 that the city agreed to rename the park “Bruce’s Beach” in honor of the evicted family. That honor, however, has been derided by critics as a hollow gesture toward the family.

While the state legislation is required to make the transfer to the family, more action on a local level will still be required. The county in July approved a roadmap for carrying out the move. In part, it calls for the county Treasurer and Tax Collector Department to work with the County Public Administrator’s Office to determine the Bruces’ legal heirs.

The county will also have to negotiate an agreement for the land transfer, one that eases the property tax burden on the descendants when they take possession. The county will also have to find land to relocate a lifeguard facility at the site.

The county’s CEO’s Office and Anti-Racism, Diversity and Inclusion Initiative is expected to report back to the Board of Supervisors this fall with further details, after evaluating the impacts of the property transfer. The plan did not provide a date by which the land would need to formally be transferred.