View Winners →

View Winners → Julius Parker – Monrovia’s Unsung Hero

Julius Parker (pictured second from the left) was awarded his high school diploma at the age of 91. –Courtesy photo

By Ralph Walker and Susie Ling

Julius Parker came to live in Monrovia in 1933. Perhaps you did not know him. But at this “Home Going Celebration” at the Monrovia United Methodist Church on April 28, 2018, so many stories came out from the hundreds gathered. There was a long line of people who wanted to share a memory. Julius was one of those guys with a genuine heart that touched so, so many. Often, the history of such individuals of color goes unrecorded in print and is then lost.

The memorial service included two beautiful renditions: “His Eye is on the Sparrow” sung by Joyce Chavis, and “Jesus Is the Best Thing” sung by Vincent Gaston. Mayor Lois Gaston told a story, “When my son, Vincent, was small, he was perturbed by the multiple sounds at Second Baptist Church services. But one day, Julius’ wife, Hazel, sang a song and Vincent never complained again.”

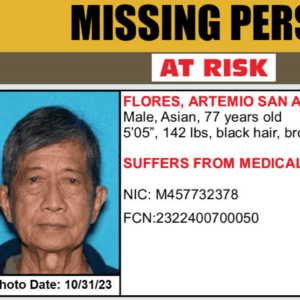

Monrovia School Board President Terrence Williams spoke on how proud he was to be present when Mr. Parker was awarded his high school diploma 74 years late. It is not often that City and School Board dignitaries gather at someone’s house to graduate them when they are 91. Steve Baker, representing the City, expressed his condolences as did Pam Barkas, representing Monrovia Historical Museum.

The church was crowded. Darrell “Rooney” Carr shared a story about how Mr. Parker helped him build a soap box car. Darrell won the race that ended at the Charles’ Store parking lot on Myrtle and Cherry. Marvin “Oka” Inouye, a Japanese American, tells of how he felt so comfortable at the Parkers’ home that they would often find him sleeping under the blankets. Marvin said, “I’m Julius’ other son, although I may not look like it.” Even Emcee Keisha Carter-Brown had to share a story of her neighbor, “At that time, I was worried about how to pay for my recently purchased home, but Mr. Parker gave me such encouragement. He said, “one day at a time.’” These stories all tell of Mr. Parker’s love for others.

Julius was born in Guthrie, Oklahoma to Ollie Wigley and Julius Parker, Sr. in 1924. His mother then married a Pullman porter, Elmer Barmore, who brought Julius and his younger sister, Dorinda, to this stop on the Santa Fe line. Ollie was a graduate of Emporia Teachers’ College in Kansas, but worked as a domestic servant in Monrovia as her teaching license was not recognized in California.

The children were attending the segregated Huntington Elementary during the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. The damage to the old brick building was so bad that many African American parents rebuked the School Board and sued, rather than allow their children back on such dangerous premises. Julius said in an earlier interview, “My mother was a fighter. She was educated and a school teacher. My mother was a Martin Luther King-type. She took no crap (laughs). She was one of the leaders. As we couldn’t go to Huntington, we went to the various homes of Black women, including my mother, and they were doing the best they could to teach us. We never got any school credit for that. Finally, they let us integrate into other schools while Huntington was being rebuilt. My sister and I went to Santa Fe School. That’s when I fell in love with Santa Fe.”

In his senior year, Julius joined World War II after he turned 18 in 1943. He said, “I left for the Army before Leroy Criss. I volunteered because I wanted to go. Leroy went about six months later.” Leroy Criss was a Tuskeegee Airmen. Julius joined the Special Services unit and served in Europe. Julius said, “We were like brothers. We were the same age and we were two of the three Blacks at Monrovia High in our particular class [at Monrovia-Arcadia-Duarte High School]. The other person was Betty Fisher. She married George Gadbury.”

After his military stint, Julius returned to Monrovia and married Hazel Powers. He wanted to build a home for his growing family but he insisted that his four children go to Santa Fe School, rather than the still segregated Huntington Elementary. “I got [my lot] from a Japanese American man. All the other real estate guys were after this lot, but Mr. Kawaguchi wouldn’t sell it to them. He sold it to me for $5,000. It was meant for me. I had to be one house west of Ivy so my kids could go to Santa Fe School. We were one of the first to build on Fig Street and I finished in 1962.” Mr. Kawaguchi had bitter feelings of Monrovia after being interned during World War II, but he must have known the Parkers would take good care of Fig Street.

Mr. Julius Parker said, “In the 1960s, I had three children at Monrovia High School. In 1969, we had massive race riots and they had to close the school. Afterwards, I was one of the parents who would go to school to look over our children. A lot of parents didn’t do what I did. I would rather miss a day from work than miss a child.” He continued, “We always said to our kids, ‘Everybody is the same regardless of race’… The cops stopped me once and all I could think of is, ‘[It is because] I’m Black, I’m Black.’ But I was wrong. I was speeding and I should’ve been pulled over… I’m not saying White people won’t do you wrong, but sometimes Black people do you wrong too. And sometimes it is your fault. Sometimes it isn’t about White or Black.”

Julius treated everyone like they were his child. He said, “When I was a kid, I decided I was going to have a good relationship with my children. I was going to be a good father. My children are fifty and sixty years old now and they say ‘Dad, I love you.’ They give me gifts. They do everything except they don’t kiss me (laughs). I have a good relationship with all of my children. There’s no excuse [not to].” In an interview with Joannie Yuille in Monrovia’s Changemakers Julius is quoted as saying, “Support the education of all children. Do whatever it takes to assure that all students have equal access… Don’t place blame; work on solutions and become a change agent.”

Julius Parker passed away on April 15, 2018 at the age of 93. We join his extended family to say, “Dad, we love you.”