View Winners →

View Winners → The value of literacy was the legacy of Col. Allensworth

– Courtesy photo

By Susan Motander

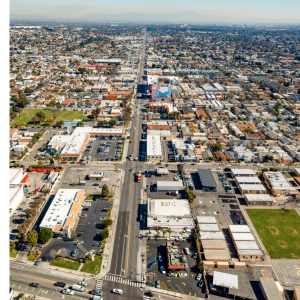

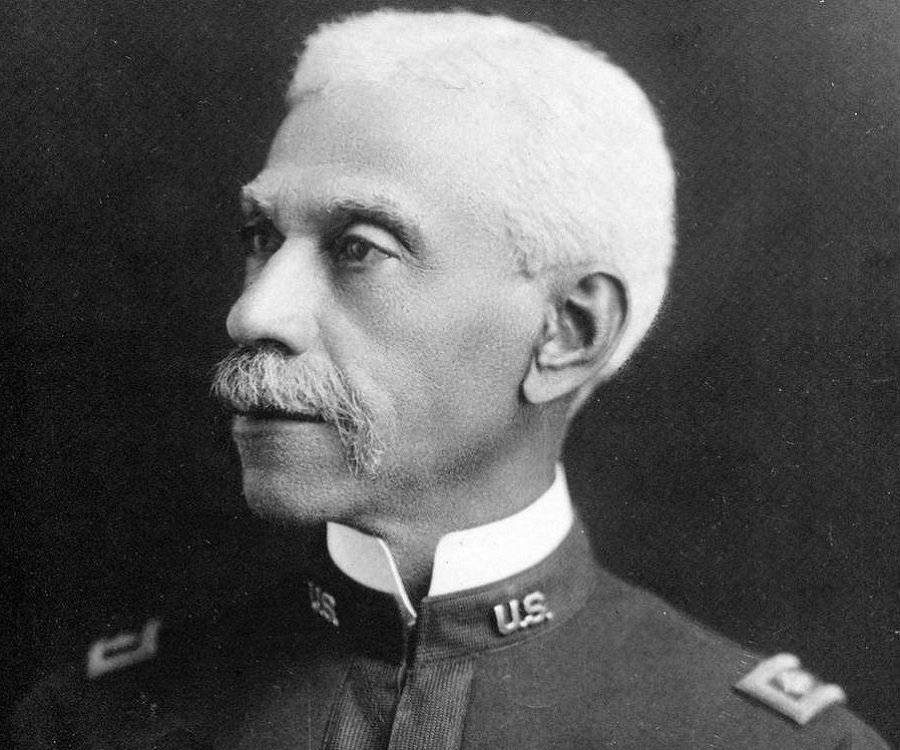

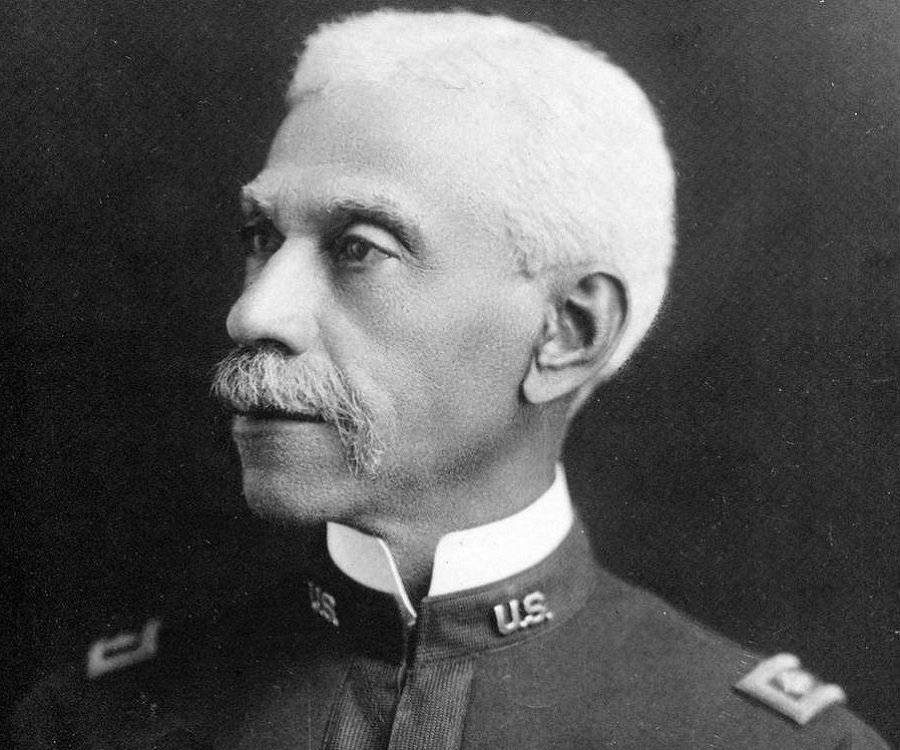

Allen Allensworth is being honored this Saturday with the unveiling of the first Neighborhood Treasure plaque at a Monrovia Area Partnership Block Party at the Second Baptist Church in Monrovia, a church he founded in 1904. Allensworth ultimately went on to fame as the founder of the central valley community that carries his name. It was the first town established, funded and governed by African Americans. Monrovia was also the site of Allensworth’s death in 1914 when he was struck by a motorcycle.

It was the journey that led Allensworth first to Monrovia and then to the founding of that community that is fascinating. Born a slave in Kentucky in 1842, he ultimately became the highest-ranking African American in the American Army at the time of his retirement after 20 years as a Chaplin. The first step on that journey was learning to read: it was his literacy that led to every opportunity that came to him.

Before the civil war, it was illegal in the South to teach a slave to read or write. The young Allen was assigned by his owner to be a companion to the owner’s son. When the son went to school, he taught Allen to read as he learned. After being sold a few times, and an attempt to escape to freedom for which he was whipped, he was literally sold down the river to a man in New Orleans who owned racehorses.

When this new owner discovered his literacy, rather than punishing the young man, he assigned him to race his best horse. In 1861 this owner took his horses to a meet in Louisville, Kentucky and took his literate slave with him. There the young Allensworth met members of the 44th Illinois Volunteer Infantry regiment. They helped to disguise him and he marched out of town and into freedom.

For a while his ability to read led him to work as a civilian nursing aid and then to assisting a doctor in Ohio. In 1863 he enlisted in the U.S. Navy where his ability to read led to his being promoted to Captain’s steward and clerk.

After the war, he worked for a while in Kentucky and then St. Louis. Allensworth put himself through formal schooling at the Ely Normal School while at the same time teaching at schools for freedmen under the Freemen’s Bureau. Ultimately, while he did not finish his schooling he received an honorary Master of Arts degree from Roger Williams University. In Louisville he began attending the Fifth Street Baptist Church where he was ordained in 1871. He continued his studies, this time in theology in Tennessee.

By 1875 he was back in his native Kentucky, now teaching in Georgetown and serving as the financial agent of the General Association of Colored Baptists. He also helped to found a college to educate black teachers and preachers, the State University that later became Simmons College of Kentucky. Allensworth also served on the school’s Board of Trustees. In 1877 he married Josphine Leavell whom he had met when both were studying at Roger Williams University in Tennessee. She was a musician playing the piano and organ and teaching music, a great aid to a young preacher. Together they had two daughters: Eva and Nella.

During this time, the young preacher became the pastor at State Street Church in Bowling Green, Ky., but continued his studies as well, studying public speaking in Philadelphia and giving lectures in Boston. The American Baptist Publication Society appointed Allensworth the Sunday School Missionary for the state of Kentucky; this enabled him to continue his work with education. All this led to his being appointed the State Sunday School Superintendent by the Colored Baptist State Convention.

With these leadership positions and with his public speaking throughout the state, it is no surprise he was selected as Kentucky’s only black delegate to the Republican National Conventions in both 1880 and 1884.

In 1886, when he was 44 years old, and with the support of both southern and northern politicians, he was appointed a Chaplain in the U.S. Army (at that time such appointments needed to be confirmed by the Senate and the President). He was one of the few black Chaplains and was assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment, better known as the Buffalo Soldiers. His family went with him on his deployments in the West, with his wife playing the organ for services.

By the time of his retirement in 1906, he had been promoted to the rank of Lt. Colonel; he was the first African American to achieve that rank. After leaving the military, Allensworth moved to Southern California and he helped to found the Second Baptist Church here in Monrovia in that year. He served as its first pastor.

In a recent history he wrote of the First Baptist Church, Monrovia’s City Historian made the following observation: In the early days of Monrovia, the First Baptist Church was instrumental in helping to establish the Second Baptist Church, a Black congregation, making a substantial monetary contribution to Second Baptist for the construction of their first church home. The Rev. Russell H. Greaves led his congregation in this act of religious unity that bridged the racial divide of those times.

Col. Allensworth only stayed with Second Baptist Church for a few years. In the same year the church was established, he met Professor William Payne, an educator in Pasadena. Together they established the California Colony and Home Promotion Association and in 1908 the purchase of 800 acres 30 miles north of Bakersfield was made. It was their dream to create an “environment where African Americans could live free from discrimination,” according to the website of the Allensworth State Historic Park,

The community they created was originally called Solita, but has become known as Allensworth. In 1909 the colony began to become a reality. People came from all over the country, drawn by the name and reputation of Col. Allensworth. Local newspaper headlines recognized the early success of the community: Tulare County Times “Negro Colony at Solita Prosperous,” Los Angeles Times “An Ideal Negro Settlement,” and Visalia Delta “Allensworth Folks Great Readers” (this latter no should be no surprise considering Allensworth’s own background.

By 1910 a school was built and by 1912 Allensworth, the community had become the state’s first African American School District. When the growth of the community required a larger school, the old one was turned into a Library and Colonel Allensworth donated his own collection of books to that Library. In 1914 the town also became a judicial district.

Unfortunately water had always been a major problem for the community. By 1914 the town had a seriously low water table. That same year saw two other major blows to the small town, First ,the railroad moved its rail stop from the town to Alpaugh in July. On September 15th Colonel Allen Allensworth died in Monrovia when he was struck and killed by two men on a motorcycle as the Reverend was crossing the street. He was in town to speak at the church he had helped to establish.

His legacy will be celebrated at the MAP Black Party Saturday. It begins at 11 am and will continue to 2 pm at the Second Baptist Church, 925 South Shamrock. A large part of that legacy was the importance of learning to read. One small white child, breaking the law and teaching one small black child to read made a huge difference, not only in that life of that child, but also impacted generations to follow because of the importance of the man that black child became.

Fitting, Monrovia Reads, the local literacy foundation will be distributing free books to the children attending the celebration of Allensworth’s life.