View Winners →

View Winners → Lawsuit filed against sheriff’s office that hired homicidal deputy

By Paul J. Young

The surviving daughter of a Riverside couple who were killed, alongside their other daughter, by a mentally disturbed Virginia law enforcement officer out to abduct a girl from their home filed suit Thursday against the agency that hired the deceased lawman, alleging negligence and other factors.

“Our law enforcement agencies and their process for screening new hires must be held to the highest standards,” plaintiffs’ attorney Alison Saros said. “These individuals are meant to protect us, but the Washington County Sheriff’s Office failed to follow the proper processes.”

Saros, who represents Mychelle Blandin, 44, and her niece, identified in court documents only as “R.W.,” filed the civil action on their behalf in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles.

The suit, which seeks unspecified monetary damages for the plaintiffs’ loss and suffering, was filed just about a year since the murders of Mark James Winek, 69, Sharie Anne Winek, 65, and their daughter — R.W.’s mother — Brooke Elizabeth Winek, 38.

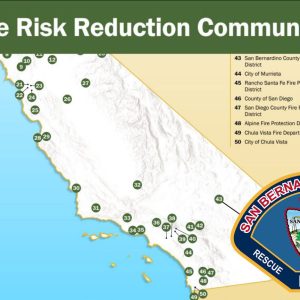

All were slain by 28-year-old Austin Lee Edwards of North Chesterfield, Virginia, on Nov. 25, 2022, according to court documents and the Riverside Police Department. He took his own life hours later during a confrontation with San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department personnel.

“Edwards never should have been hired by the Washington County Sheriff’s Department,” plaintiffs’ co-counsel David Ring said. “He was barred by the courts from owning or possessing a gun because of his mental illness and because he was a danger to the community.”

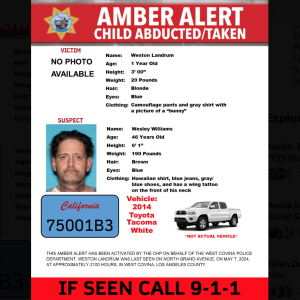

Edwards drove roughly 2,500 miles to rendezvous with Brooke Winek’s 15-year-old daughter at her grandparents’ home at 11261 Price Court. Police said Edwards was involved in a predatory “catfishing” relationship with the girl, convincing her via online chats that he was a 17-year-old boy.

He arrived the morning after Thanksgiving, and according to the civil complaint, he represented himself as a “detective,” flashing his Washington County sheriff’s badge and telling Mark and Sharie Winek that he needed to question them in connection with unspecified online activity involving their granddaughter R.W., who was then running errands with her mother.

“Edwards instructed Sharon to call Brooke,” the complaint stated. “Sharon told Brooke that the detective wanted Brooke and R.W. to come to the home immediately.”

Minutes later, the lawman directed Sharon Winek to call her other daughter, Mychelle Blandin, who was instructed by Edwards via Sharon to tell her younger sister “to leave all cell phones in the car and (for Brooke) to come inside the home first, leaving R.W. in the car,” according to the narrative.

Brooke Winek complied, entering the Price Court residence without her daughter, who remained in the car. However, the girl became restless after a short period and she had received no indication of what was transpiring in her grandparents’ residence.

R.W. went into the house and “discovered Edwards had murdered her mother by slitting her throat,” the complaint said. It included a coroner’s report, though, indicating Brooke Winek’s spinal cord was severed from a stab wound to the neck.

“Edwards had also attempted to murder her grandparents by asphyxiation,” according to court papers. “Her grandparents were both hog-tied with bags over their heads, but at least one of them was still moving when R.W. entered the home.”

Both ultimately died from lack of air, an autopsy showed.

Edwards set fire to the residence and led R.W. out of the house to his Kia Soul. As he was making his getaway with the teen, an alert neighbor called 911, concerned for her safety after sensing there was a problem.

Patrol officers were headed to the location when 911 dispatchers began receiving reports of a fire on the cul-de-sac. Crews quickly knocked down the blaze inside the Winek home and discovered the victims’ bodies.

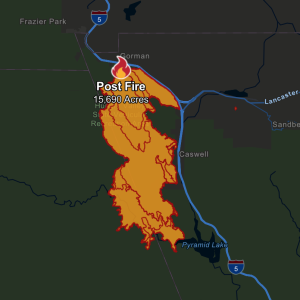

Edwards’ vehicle was quickly identified, and a region-wide search was initiated, culminating in a pursuit by San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies, who spotted the car going northbound on Highway 247 and then 62.

The off-duty lawman lost control of the car and drove off the road. R.W. fled, and Edwards got out and leveled his pistol at a sheriff’s helicopter, prompting deputies to open fire. It was at that point he fatally shot himself, police said.

R.W. was uninjured. She’s now in the care of her aunt Mychelle Blandin.

The complaint alleges the Washington County Sheriff’s Office is “vicariously liable for the wrongful acts of Edwards.” The plaintiffs said the agency failed to appropriately vet him prior to hiring him, providing him with a service firearm when Virginia law prohibited him from being in possession of any type of gun.

“The sheriff’s office should have known about Edwards’ mental health history,” court papers stated. “The agency’s negligence in hiring, supervising and retaining Edwards was a substantial factor in his carrying out the murders.”

He was a Virginia state trooper from January 2022 to October 2022, when he resigned and then applied to work for the sheriff’s office. He had been employed less than a month when he committed the murders.

Evidence later surfaced that Edwards had previously engaged in online harassment of another girl years earlier, obsessing about her to the point of threatening suicide if she did not respond to his messages.

He was briefly committed to a mental hospital in 2016 after an altercation with his father in which he threatened to kill the elder man and also cut himself, according to court documents.

“Edwards was held on a temporary detention order and admitted to a treatment facility, which prevented him … from buying or possessing a firearm until that right was restored by a court,” the complaint said. “Edwards’ right to buy or possess a firearm was never restored by a court.”