View Winners →

View Winners →

By Paul J. Young

The Board of Supervisors on Tuesday approved a funding agreement with the California State Bar for $4.98 million to cover costs incurred by the Riverside County Office of the Public Defender in handling a program that seeks to treat mentally ill individuals who are on the streets, at risk of homelessness, or likely to end up behind bars.

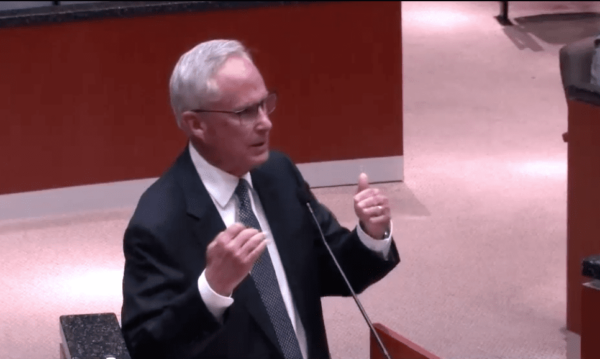

“The people who benefit from this are needy people, sick people in many ways,” Public Defender Steve Harmon told the board. “This is an attempt to help them. It’s new. It may be successful; it may not be successful. We’ll do everything we can to make it successful.”

The Bar funding compact tied to the Community Assistance, Recovery & Empowerment, or CARE, Act is the first direct allotment received in Riverside County since the program went into effect on Oct. 1. The act, signed into law as Senate Bill 1338 in 2022, establishes new protocols for placing those with behavioral health disorders in treatment regimens operated by the county.

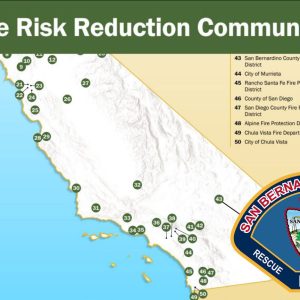

The new CARE Courts are currently designated in Riverside, Glenn, Orange, San Diego, San Francisco, Stanislaus and Tuolumne counties. California’s remaining counties will be required to establish protocols by December 2024.

The $4.98 million provided via the state Bar’s Legal Services Trust Commission will go directly to funding positions in the Office of the Public Defender to render legal aid to CARE Court recipients, responding to “their stated interests” at every stage of proceedings.

Officials said the preference is for nonprofit legal clinics to step in and represent parties, but when those services aren’t available, deputy public defenders will have to be appointed.

Harmon said that in the last two weeks since the program went live, four referrals have been received by the Office of the Public Defender.

“The numbers are very low, but it’s just getting off the ground,” he told the board. “We’re only hiring as necessary. We’ll watch this very carefully and err on the side of bringing less people in than more. If all funding stops, and we have these additional county employees … we will absorb them into our regular operations.”

The office intends to hire a new supervising deputy public defender, two line deputy public defenders, four social services practitioners, four legal support assistants and two paralegals, according to Harmon.

“It’s going to be just the public defenders in court, working to encourage clients to receive these services,” he said. “There won’t be a lot of contesting moments. It’s social worker-intensive. And it’s completely voluntary. There are no repercussions if someone falls out of the program.”

The aim is to prevent mentally ill people from falling through the cracks of the social service system, ending up in a correctional facility or living on the streets without any help toward rehabilitation. The CARE Court is designed for those “in the schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders,” according to documents posted to the board’s agenda.

If they are not in a voluntary treatment plan, patients can be processed by the court. According to the legislation, the prospect must be “unlikely to survive safely in the community without supervision, and the person’s condition is substantially deteriorating; the person is in need of services in order to prevent a relapse or deterioration that would likely result in grave disability or serious harm to the person or others.”

Through civil proceedings, relatives or close friends of mentally ill residents, doctors who have interfaced with them, law enforcement officials and other first responders can initiate CARE Act cases by submitting referrals or petitions seeking to commence proceedings. The idea is to establish customized treatment plans, using all available public resources.

The Riverside University Health System-Department of Behavioral Health will serve as the lead agency responding to cases.

Judges can refer cases to the CARE Court if they determine a criminal defendant is “mentally incompetent.”

A “CARE agreement” will be necessary before any treatment plan could move forward, with progress hearings scheduled to determine whether the party is benefiting from treatment or cannot be helped. A treatment plan will specify psychiatric services, including “stabilization medications,” bridge or transitional housing available for the party, as well as other social safety net options.

Department 12 of the Riverside Historic Courthouse has been designated as the county CARE Court. Hearings will be held Monday to Friday in the afternoons.

The state Bar funding agreement runs to the end of fiscal year 2024-25.

The Legislature allocated $39.5 million in General Fund appropriations to support CARE Act applications in the current fiscal year. Ongoing funds will be generated, in part, by the imposition of fines on counties that don’t comply with provisions of the act. However, Harmon noted that secure long-term funding sources haven’t been identified going forward.

“The program may lose political favor (with the Legislature),” he said.

The county’s CARE line is 800-499-3008. Additional information is also available at ruhealth.org/behavioral-health/care-court.