By Fred Shuster

As the top federal prosecutor for the Central District of California — which includes Los Angeles, Orange and Riverside counties — U.S. Attorney Martin Estrada says his overriding goal is making an impact in the lives of the most vulnerable.

That includes children, the elderly, immigrants and other groups that seem powerless against criminals of all sorts — from perpetrators of child sexual exploitation to operators of fraud and extortion schemes, Estrada told City News Service.

When his office is litigating on behalf of such victims, Estrada said, it is “doing work that benefits the community as a whole.”

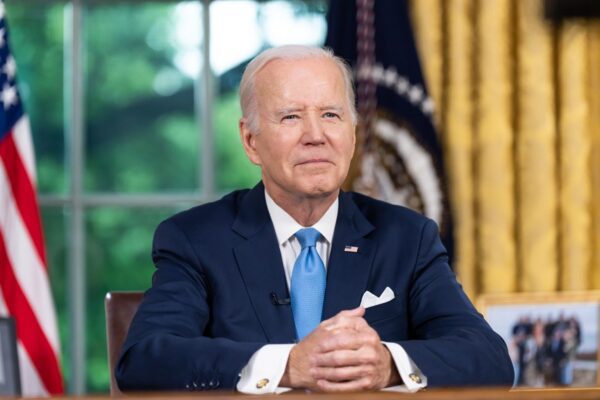

The lawman, whose parents immigrated to the United States from Guatemala, was nominated by President Joe Biden, unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate and sworn in as the U.S. Attorney for the Central District in September. During a previous turn as a federal prosecutor in the office based in downtown Los Angeles, Estrada served as deputy chief of the Violent and Organized Crime Section and as International Organized Crime Coordinator.

In private practice, he maintained a busy pro bono practice in the areas of immigration, education and indigent services. Some of his most notable work included representation of the Bruce family in successfully defeating a lawsuit that sought to prevent Los Angeles County from returning to the family beach-front land known as “Bruce’s Beach” that was wrongfully taken from the family through a discriminatory condemnation action in the 1920s.

As head of federal prosecutions in the Central District of California — the nation’s most populous jurisdiction, covering seven counties and nearly 20 million people — Estrada, 45, oversees all federal government litigation for the Criminal, National Security, Civil, and Tax Divisions, including cases involving public corruption, civil rights violations, corporate fraud, cybercrime, domestic and international terrorism, violent and organized crime and other forms of illegal activity.

Since Estrada took office, the Central District has obtained the convictions of, among others, longtime Los Angeles politician Mark Ridley-Thomas in a public corruption case; senior members of a violent transnational criminal street gang; numerous defendants who caused death by distributing pills laced with fentanyl; men from throughout the region who produced and/or distributed child sexual abuse material; crooked attorneys; defendants who manufactured and sold unregistered “ghost guns”; and people who perpetrated hate crimes based on race or religion.

The U.S. attorney sat down with City News Service for a discussion of his job and issues of importance to him. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Q: What are your goals as chief federal prosecutor in the district?

A: There are three priorities: community outreach, reaching groups that traditionally have not had a lot of connection to our office, including Latino and Spanish-speaking communities and Native American groups; increasing the diversity of attorneys in the office; and doing impact work — work that is meaningful to the community, which is why we’ve done so much work in the civil rights context.

Q: In terms of the Ridley-Thomas case, is public corruption another priority?

A: We’ve put a lot of resources there, and have been aggressive in appropriately and ethically bringing the cases. When someone breaches their trust to the community as a politician or breaches their duty to protect and serve as a law enforcement officer, it’s more than just that particular case. It has repercussions that reverberate throughout the community. The bottom line is politicians are obligated to do things in an ethical manner, to do things only in the interests of their constituents, and not operate for their own personal benefit or for the benefit of family members.

Q: People sometimes call for leniency in cases involving public officials who may have done some good for their community prior to the charged conduct. Should that count?

A: I can’t talk about sentencing. That’s for judges to determine and they take it all into consideration. But while some defendants may have done some good in their lives, that doesn’t mean they can get away with criminal conduct. Many defendants in the fraud context have done good things and bad things — that’s for the judge to decide. It doesn’t mean we turn a blind eye to criminal activity.

Q: Are ghost guns an increasing concern?

A: The fact that someone would want to obtain a ghost gun is concerning. It suggests already that there’s some nefarious purpose in having the gun. The reality is those guns are likely going to be used in some sort of violent incident. By seizing those guns, in our view, we’re preventing a violent act from taking place. We’ve seen more of these guns out in the community, and we’re seizing more. My office recognizes that violent crime is a major issue not just in our district, but throughout the country. So we’re going to bring cases that act to reduce violent crime.

Q: We’ve talked about the criminal side of the office. How about federal civil prosecutions?

A: The civil side is just as powerful as the criminal side in terms of creating change and improving people’s lives. People need to see that no one is above the law, whether you’re a corporation with power and resources, the government will still vigorously investigate and prosecute those violations when they effect consumers throughout our district. When I look at (potential) cases, I’m not thinking about my own feelings, I’m thinking about what the community needs.

Q: What kinds of cases make the most impact?

A: When we have public officials, law enforcement officers who breach their trust, that has huge impacts on the community and has to be addressed. Fraud against vulnerable groups like immigrants who are victimized daily, crimes against children — those have devastating impacts certainly on the individual child but also on families and communities. We’ve been prosecuting those crimes very aggressively.

Q: What made you want to get into the law as a career?

A: I was driven to become a lawyer by wanting to help others. I saw it as a path to helping my community.