UC San Diego School of Medicine researchers have discovered a connection between cellular metabolism and depression, finding compounds in the blood of those with depression and suicidal thoughts, according to research published Friday.

The findings, published in Translational Psychiatry, reveal that measuring those markers of cellular metabolism could be a vital approach to studying mental illnesses and developing new ways to diagnose, treat and prevent them.

“Mental illnesses like depression have impacts and drivers well beyond the brain,” Dr. Robert Naviaux, professor in the Department of Medicine, Pediatrics and Pathology at the UCSD medical school, said in a statement. “Prior to about 10 years ago, it was difficult to study how the chemistry of the whole body influences our behavior and state of mind, but modern technologies like metabolomics are helping us listen in on cells’ conversations in their native tongue, which is biochemistry.”

Major depressive disorder affects 16.1 million adults in the United States and costs $210 billion annually, the researchers write. While the primary symptoms of depression are psychological, Friday’s study helps further the idea that depression is a complex disease with physical effects throughout the body.

While many people with depression experience improvement with psychotherapy and medication, some people’s depression is treatment-refractory, meaning treatment has little to no impact, the authors write. Suicidal thoughts are experienced by the majority of patients with treatment-refractory depression, and as many as 30% will attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime.

“We’re seeing a significant rise in midlife mortality in the United States, and increased suicide incidence is one of many things driving that trend,” Naviaux said. “Tools that could help us stratify people based on their risk of becoming suicidal could help us save lives.”

The researchers analyzed the blood of 99 study participants with treatment-refractory depression and suicidal ideation, as well as an equal number of healthy controls. Among the hundreds of different biochemicals circulating in the blood of these individuals, they found that five could be used as a biomarker to classify patients with treatment-refractory depression and suicidal ideation. However, which five could be used differed between men and women.

“If we have 100 people who either don’t have depression or who have depression and suicidal ideation, we would be able to correctly identify 85-90 of those at greatest risk based on five metabolites in males and another five metabolites in females,” Naviaux said. “This could be important in terms of diagnostics, but it also opens up a broader conversation in the field about what’s actually leading to these metabolic changes.”

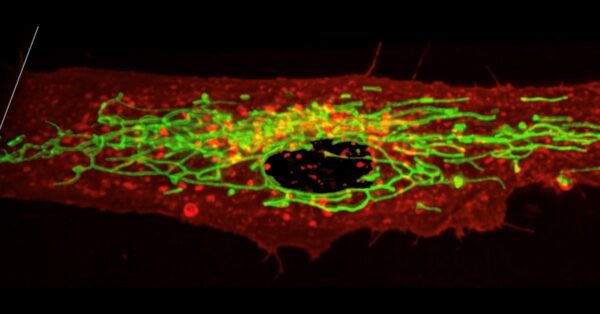

Some metabolic markers of suicidal ideation were consistent across both sexes. This included biomarkers for mitochondrial dysfunction, which occurs when the energy-producing structures of our cells malfunction.

Mitochondria produce ATP, the primary energy currency of all cells. ATP is also an important molecule for cell-to-cell communication, and the researchers wrote it is this function that is most dysregulated in people with suicidal ideation.

Because some of the metabolic deficiencies identified in the study were in compounds that are available as supplements, such as folate and carnitine, the researchers are interested in exploring the possibility of individualizing depression treatment with these compounds to help fill in the gaps in metabolism that are needed for recovery. However, Naviaux said these supplements are not cures.

“If we can find ways to treat depression and suicidal ideation on a metabolic level, we may also help improve outcomes for the many diseases that lead to depression,” he said. “Many chronic illnesses, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome, are not lethal themselves unless they lead to suicidal thoughts and actions. If metabolomics can be used to identify the people at greatest risk, it could ultimately help us save more lives.”