In 2023, more than 650,000 people in the United States experienced homelessness. The number is a record since data collection began in 2007, and means more people than ever are confronted with the unique health risks that come from living without stable housing.

Homelessness can take many forms, from couch surfing to living in a shelter to sleeping on public streets. In a country like the U.S., where access to health care is determined by someone’s ability to pay, the economic instability that puts someone at risk of homelessness is also bound to have a direct impact on their health.

The life expectancy of people experiencing homelessness is between 42 and 52 years old, according to a study from the University of Pennsylvania published in 2022. Meanwhile, the overall life expectancy in the U.S. is 76 years old.

Foothold Technology used data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to explore how access to housing impacts health, and vice versa.

Some of the health risks from cold winters, air pollution in dense cities, and extreme heat may seem obvious, but internal and chronic health conditions also fuel shorter life expectancies for unhoused people.

A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association published in 2023 examined deaths among unhoused people in San Francisco over eight years and found the sudden mortality rate was 16 times higher than the housed population. Sudden mortality events include heart attacks, drug overdoses, strokes, and more. Even when the researchers adjusted to remove drug overdoses and focus exclusively on cardiac events where a defibrillator could intervene, the sudden mortality rate remained seven times higher.

Another study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that people experiencing homelessness were 3.2 times more likely to die within a six-month period than housed people. They remained 1.6 times more likely to die within a six-month period than low-income, housed individuals.

The connection between access to housing and health is also cyclic. Just as homelessness can worsen health outcomes, health problems can also lead to homelessness.

Certain disabilities and health problems can limit available job opportunities, and the high cost of medical treatment can be burdensome — even for those with consistent income. About 8% of people hold medical debt in the U.S., but the share jumps to 14% for people in fair health, and 20% for people in poor health.

Health issues are harder to manage without stable housing

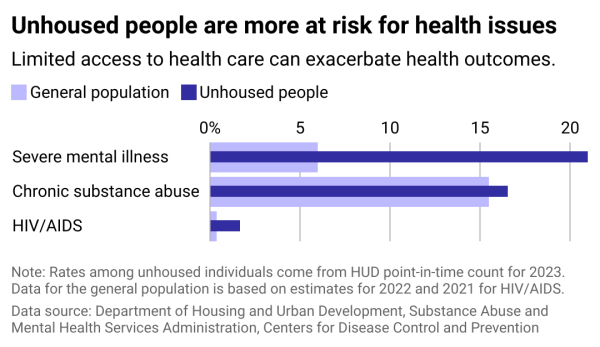

Seeking treatment for chronic health issues can be a challenge when 60% of unhoused people are without health insurance. Although HIV/AIDS can be managed and prevented with medications today, limited access to such care has resulted in higher diagnosis rates among the unhoused population.

Economic and housing instability can exacerbate mental health conditions, and severe conditions can make it more challenging to hold a job and interact with people.

When it comes to mental health and substance use disorders, the national program Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness connected with more than 100,000 unhoused people also experiencing serious mental health conditions in 2021. Nearly 60,000 enrolled in a variety of their services including screening and treatment, rehabilitation and housing services.

The wider availability of overdose-reversing drugs like naloxone has also been effective for intervening in emergency situations. The National Institutes of Health estimates that the distribution of naloxone kits has reduced overdose deaths by 6%.

Other health care issues can be especially difficult to manage without having a consistent roof over one’s head. The FDA recommends diabetes patients keep insulin in the refrigerator. Diet-related conditions like hypertension are harder to manage without access to a kitchen to prepare unprocessed foods.

Estimates suggest that people experiencing homelessness also more often live with disabilities. Among the sheltered homeless population in 2021, 57.3% had disabilities compared to 13% of the American population overall.

A whole-person health approach

In 2016, California began rolling out programs to coordinate the health care needs of its population with the social service needs of its population. This includes helping connect patients with housing and food resources and allowing federal health funding to be used for certain housing services. This “whole person care” approach has shown success in the state, where 13 million people are enrolled in Medicaid.

The program showed success in its first five years. A 2021 report from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research showed enrollees reported 45 fewer hospital stays and 130 fewer emergency room visits for every 1,000 beneficiaries compared to similar-profile Medicaid beneficiaries who did not participate in the program. This also reduced Medicaid payments by $383 per beneficiary per year.

Also in California, newly legalized mobile pharmacies will now be able to immediately dispense uncontrolled substances to patients without permanent addresses.

California isn’t the only state beginning to use Medicaid funds for food and housing needs. Several other states — including Arizona, Arkansas, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oregon and Washington — have launched pilot projects.

Nevada’s program will cover rent and food costs for eligible participants as well as housing transition services, case management and deposits for housing. State Medicaid Administrator Stacie Weeks told the Nevada Current that the state’s program was a “small piece of the puzzle to improve health outcomes and lower the risk of high health care costs that can come from being unhoused.”

Written by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on Foothold Technology and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio. The article was copy edited from its original version.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.