Wouldn’t it be incredible to practically step back in time and experience what it was like to live in a rural village in 18th century Japan? Starting on Oct. 21, visitors to The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens will have that unique opportunity when the Shōya House opens at the Japanese Garden (read previous article about the Shōya House here).

During the press opening held on Oct. 13, Karen Lawrence, president of The Huntington, expressed her gratitude for the generosity of the Yokoi family who gifted their ancestral home to the beloved institution.

Lawrence remarks about this exceptional new destination at The Huntington. “This restored residential compound is truly a masterpiece and it offers a glimpse of life in rural Japan some 300 years ago. It’s the only example of this kind of architecture in the U.S. and its presence here wouldn’t have been possible without the generosity of the Yokoi family.”

“In Japan, the house was disassembled, restored, disassembled again, and shipped to us at The Huntington,” Lawrence adds. “Once the components of the house arrived, it was up to The Huntington to rebuild and provide context, including recreating the landscape and gatehouse.”

It’s only fitting for the Shōya House to join the distinctive house Henry E. Huntington bought from Pasadena businessman George Turner Marsh that has been at the Japanese Garden, which has such a fascinating history. The Huntington’s information kit gives the following chronology.

The building of the Japanese Garden began in 1911 and was completed in 1912. The garden, which is currently 12 acres, was inspired by the widespread Western fascination with Asian culture in the early 1900s. Henry E. Huntington purchased many of the garden’s plants and ornamental fixtures, as well as the Japanese House, from a failed commercial tea garden in Pasadena, located at the northeast corner of Fair Oaks Avenue and California Boulevard. When The Huntington opened to the public in 1928, the Japanese Garden became a major draw for visitors. Features such as the bell tower and bridge were newly built for the garden by Japanese American craftspeople.

By World War II, staffing shortages — including those resulting from the incarceration of Japanese American employees — and the political climate led to the closure of parts of the Japanese Garden, and the Japanese House fell into disrepair. In the 1950s, members of the San Marino League helped support the refurbishment of the buildings and surrounding landscape.

In 1968, The Huntington expanded the Japanese Garden to include a bonsai collection, which now numbers in the hundreds, and a rock garden, the Zen Court. Since 1990, The Huntington has served as the Southern California site for the Golden State Bonsai Federation.

The ceremonial teahouse, called Seifū-an (the Arbor of Pure Breeze), was built in Kyoto in the 1960s and donated to The Huntington by the Pasadena Buddhist Temple. In 2010, the teahouse made a return trip to Japan for restoration, overseen by Kyoto-based architect Yoshiaki Nakamura (whose father built the original structure). It was then shipped back to San Marino and reassembled.

In 2011, a team of architects with backgrounds in historic renovation, horticulturists, landscape architects, engineers, and Japanese craftsmen undertook a yearlong, large-scale restoration of the historic core of the garden. The project included repairs to the central pond system and water infrastructure, along with increasing pathway accessibility and renovating the original faux bois (false wood) ornamental trellises.

The Japanese Garden continues to be a popular attraction to this day. However, as Lawrence points out, “What was missing was a traditional Japanese residence that could demonstrate the important historical relationship between the Japanese people, their culture, and the landscape. The iconic Japanese house in the original garden provides the idea of a Japanese residence but it wasn’t really lived in.”

Lawrence clarifies, “The shōya house is completely different. It’s an exquisite example of a village leader’s residence where rural village life can be explored through the lens of 18th century architecture and farming practices. The residence was occupied by one family, generation after generation, over the course of three centuries. Mr. Yokoi is the 19th generation to own the house.”

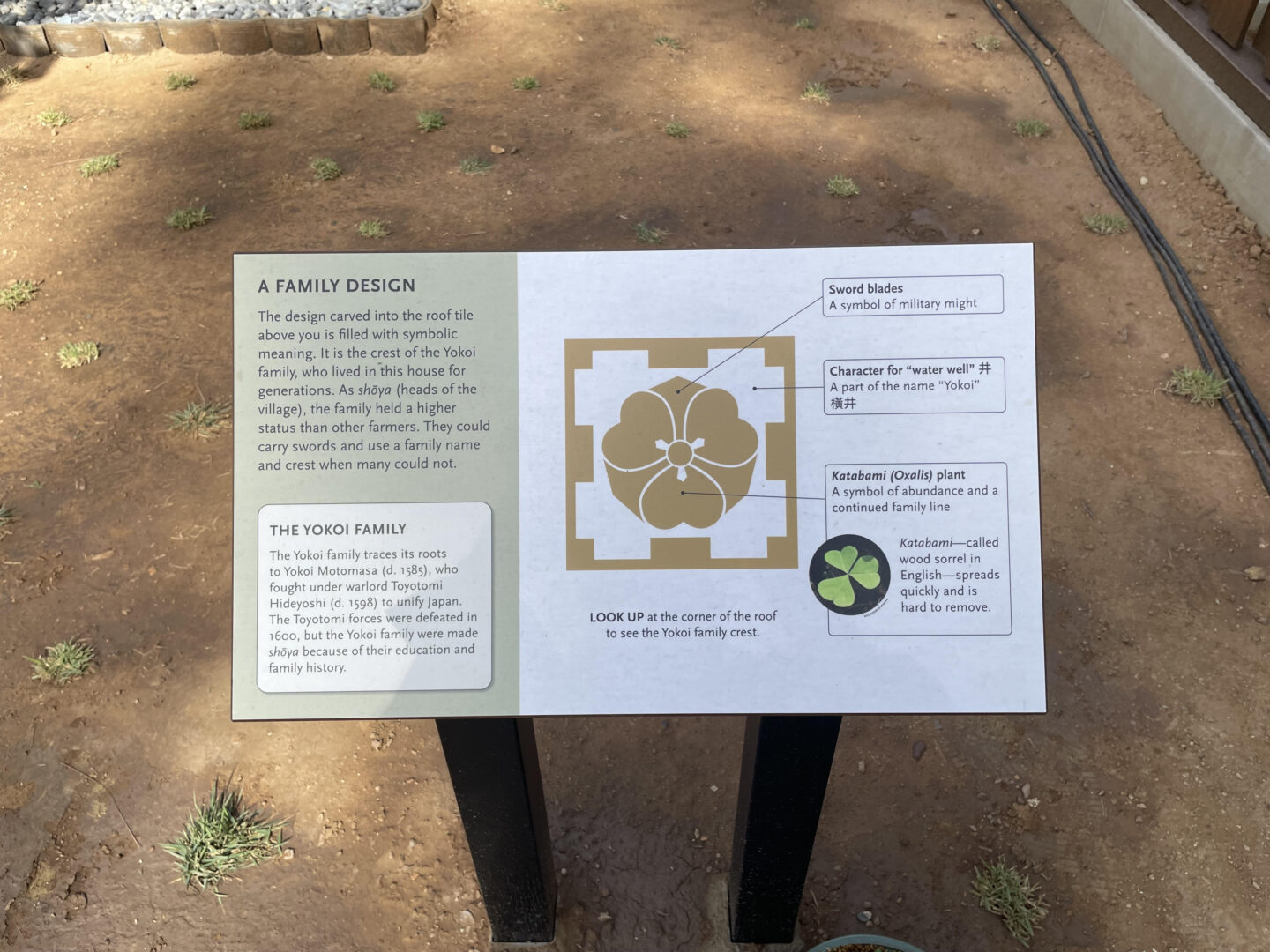

“Today it provides us with a rich aesthetic experience of the beauty of Japanese building art and many insights into what it means to live sustainably on the land,” Lawrence adds. “We were fortunate to have artisans come from Japan to work alongside local architects, engineers, and construction workers to assemble the house here and recreate elements that would have surrounded it at the time when it housed a village leader or shōya. They created the wood and stonework features you see, as well as the roof tiles and plasterwork prioritizing traditions of Japanese carpentry, artisanship, and sensitivity to materials.”

Lawrence concludes by voicing her opinion that this will become a major visitor attraction in Southern California, as well as a primary resource for architects, scholars, students, teachers, and others interested in the complexities and beauty of traditional Japanese design, craftsmanship, and architectural practices. And that visitors it will appreciate the lived experience of what this meant and how it was sustained for 300 years.

Robert Hori, gardens cultural director and programs director, says, “It has really taken an entire village to build the head of a village’s house. It wasn’t just the botanical gardens, everyone at The Huntington has contributed in interpreting the house which will make a full experience for the visitors. They won’t be looking at an exhibit in a museum, they will be in that museum. They’ll be able to participate in rice planting, and see the changes of the season. This is something that exists nowhere else and can only live at The Huntington.”

The construction team that undertook this project was headed by Yoshiaki Nakamura of Nakamura Sotoji Komuten, who oversaw the restoration of the teahouse in 2010. Hori discloses, “When Mr. Nakamura first came to The Huntington about 15 years ago, he toured it and he said, ‘Wow, this is something special.’ He saw the resources in the library (each year we have over a thousand scholars) and he said, ‘I want to create something that students, teachers, and researchers can explore and be inspired by.’ He wanted to bring traditional building and garden techniques here at The Huntington so they can be a primary resource for those who are not going to Japan.”

“We have also been blessed to have the partnership of many architects and professionals, including Mike Okamoto (U.S. Architect of Record),” continues Hori. “He has been a valuable partner in reassembling this house. You can imagine the challenges of bringing not just a 300-year-old house and re-erecting it, but bringing the metric system and having it meet U.S. building code. We are likewise fortunate to have Takuhiro Yamada (Hanatoyo Landscape Co. Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan) doing the landscape and really putting together the program.”

“What we’d like to show is the beginning of landscape,” Hori expounds. “And that design starts with the ability to control water and to move earth — and that’s exactly what a farmer is doing. We want visitors who go on a tour of the house to have the experience of being transported to 18th century Japan.”

Each time Hori gives a tour of the Shōya house, he begins at the terraced agricultural field, where he notes a whole new animal population has taken as their home. “You’ll notice the terrain is sloped — this is how many of the farms were in Japan because it’s the most efficient way to move water from uphill to downhill.”

Throughout the tour Hori impresses on everyone how these sustainability practices were a matter of survival for farmers centuries ago. And that sustainability is one of the biggest challenges we face today globally.

It’s an issue that Nicole Cavender, Telleen/Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens, deeply cares about. She states, “I’d like to emphasize one aspect in particular that’s especially near and dear to me — we have here a model of sustainability practices. You’ll see how in this house, in this landscape, we’ve integrated and showcased the historical integration of agricultural systems, how water can be used and recycled. In the front as you come in, you see the agricultural landscape that showcases sustainable practices of using cover crop and companion planting. I’m really excited to be able to share these practices and hope to inspire people to integrate them into their own life.”

Without hammering our head with it, The Huntington makes a compelling argument for practicing sustainability. By restoring the Shōya house and recreating the landscape which will grow vegetables and various crops that change through the seasons — and showing how the village head and townspeople lived — we will witness for ourselves how extraordinary beautiful the outcome can be. Would that in the foreseeable future, Cavender’s hope that their efforts to persuade us to do as these villagers did in 18th century Japan come to fruition.