By KRISTY RAMIREZ

Hundreds of Black and Mexican families plan to file claims Thursday seeking millions of dollars in restitution from the city of Palm Springs for being forcibly evicted from the downtown Section 14 neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s.

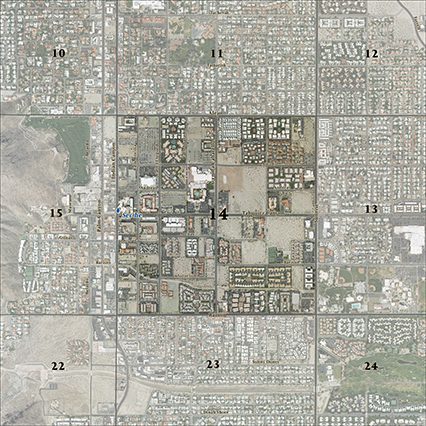

Section 14 was the primary residential area for people of color, with the one-square-mile neighborhood owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians from 1930 to 1965. The evictions began in late 1954 and continued for 12 years through 1966.

Attorneys representing evicted families will hold a news conference in Los Angeles Thursday to announce the damages claim, demanding reparations.

“You will have survivors of the evictions, who remember them vividly and talking about their experiences, how happy they were, what those evictions did to them and their families,” Lisa Richardson, a spokeswoman for attorneys representing the families, told City News Service Wednesday. “How the city of Palm Springs had their houses bulldozed and had the city fire department set fire to their homes. They will talk about what that experience has been like for them.”

An economist working for Section 14 survivors and descendants, Julianne Malveaux, will also speak during the event about the calculated millions of dollars of harm that the evictions have caused, Richardson said. The attorneys said the overall damages could range into the billions of dollars.

The city of Palm Springs formally apologized in September 2021 for the evictions, and the City Council asked its staff to develop proposals for possible economic investments that could act as reparation for the destruction of the Section 14 neighborhood. The city also removed a statue of Frank Bogert — who was Palm Springs mayor at the time — from the front of City Hall.

The resolution approved by the council last year stated that “Mayor Bogert and Palm Springs civic leaders persecuted their lower-income constituents who resided on the land owned by local Tribal Members. Attempting to dispossess the Indians of their tribal lands, and erase any blighted neighborhoods that might degrade the city’s resort image, Palm Springs officials developed and implemented a plan that included having non-Indian conservators appointed by a local judge to manage the Indians land claiming they were unable to manage it for themselves. The successful implementation of this plan resulted in the removal of the city’s people of color and restructured the race and class configuration of the city.”

An estimated 200 homes were destroyed in the mass eviction process, according to the city.

Richardson said that despite the city’s actions last year, the city has yet to provide any compensation or restitution to anyone impacted by the evictions. She said there are more than 500 survivors and descendants of those who were evicted.