Featuring beautiful explosions, unmoored islands, and rolling hills that seem to stretch on forever, the surreal landscapes featured in Sean Higgins’ work imply a contemplation of the line between fantasy and reality. But the Glassell Park-based artist has been living in Los Angeles since 2001, where reality is always a rent check and a few utility bills away.

In the first of an ongoing series of conversations with local creatives, we talk to Sean about how he balances the demands of making a living with making art.

What kind of art do you make?

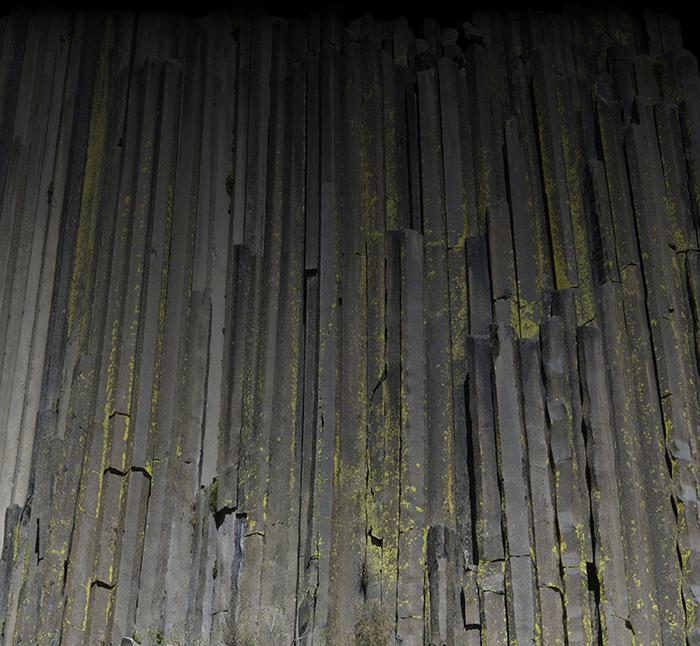

I make primarily photo-based work. This is always a tough question for me, because what I make ends up looking like photography, but it’s digitally manipulated in a way that can be very subtle, so that the viewer isn’t necessarily aware that there’s manipulation happening. From a quick glance, it looks pretty believable, but only later do you sense that something is off, or that it’s not a possible scenario.

But yeah, it’s all photo based and then Photoshop based, and then also thrown in there is a little bit of appropriation and reconfiguration.

What does that mean?

So for example, I did a series a couple years ago that was based on all of these photos that I found in the NASA online archive, and those were heavily manipulated to remove them from the NASA context a little bit. They ended up being either pushed into something that’s more sci-fi, there were a bunch of pieces that were rocket launches where I removed the rockets from the launches. So they ended up looking more like these apocalyptic explosions. So I’m taking this thing that’s pretty spectacular and just changing the context a bit.

Now I’m working on a series of landscapes. They’re stacked landscapes, and again, they look pretty believable, because they’re these rolling hills. But in the end, it’s like 10 or 15 different landscapes that have been stacked vertically on top of each other to create a rolling hill effect.

So it looks like a rolling hill, but you’re like, that’s not possible.

Exactly. And then the scale changes too. But then the color is pretty homogenous in them, so it looks believable, but then you look close, and there’s like a road that will go over a hill, and then over the next one, it’s bigger instead of being smaller. So the perspective sort of jumps around from horizon line to horizon line.

When did you start making art?

It’s funny because I just came back from visiting my parents, and they just moved to a new house. When I moved to California, I put all the artwork that I made in undergrad and grad school in their basement. And since they moved, they asked me nicely to deal with all my junk, so I had to go back to Pennsylvania and sift through all of it. I opened up a portfolio of drawings that I did as an undergrad and thought, wow, these are the drawings that first made me feel like I was a real artist. And that was probably ’96. They’re not good by any stretch, but I actually kept a couple and shipped them back to myself. There was that little light bulb that went off then and I thought, “oh, this is something I really want to do.”

So you realized you wanted to be an artist in college. Not before then?

No, I went to college for biology originally. It was a liberal arts college, so it wasn’t art school, which was good for me regardless of what I ended up majoring in in the end. I discovered art along the way. I always interested in it, and I was good at drawing, so I was always encouraged to do that. But I started off being more interested in pursuing science and doing something maybe more practical.

So you didn’t end up majoring in biology?

Well, I don’t think I was required to declare a major until later, but I was on the biology track. I actually did switch to art later. But there was a period there in the middle where I was doing half and half. You could make independent study classes there, so I made up this class where I wanted to learn how to do photo microscopy, so I did like color darkroom stuff, but with photos that I took through a microscope.

That’s interesting. You were sort of creeping over even while clinging to biology.

Yeah, it was a transition. It wasn’t a smooth cut. And that’s sort of stuck with me in my work. I’m always interested in NASA stuff, or playing with science a little bit. Or just being inspired by it.

So you graduate with a degree in art, what do you do?

Went right into grad school. I didn’t take any time off. Which was probably a good thing, because I didn’t have any direction, really, beyond “I like this art thing and I kind of want to do this.” It was actually a fight with me and my folks, because I didn’t want to go back to school right away. I wanted to try to figure out what I was going to do with my life, and they knew that if you get your MFA you could teach college, so they said, “you need to go teach college, that’s a good career and you can actually make a living.” And at that point I had been teaching summers at Skidmore College. One of my professors, who I became good friends with, went to undergrad there and would go back in the summers and teach. I started going up there and working as his teacher’s assistant. So I had this taste of what it was to teach at a university, and I guess I let my parents convince me that that was the right thing to do. So I was done with my MFA at 25. It was great in a way because it kind of made me feel like, “I’m a real artist and I just did my MFA. I’m done and I’m out and I need to make work.” But the other side to that was that I was completely burnt afterwards. I didn’t really make much for the first year or two after school. I was too fried.

So did you in fact start teaching?

I did a little bit of teaching, but I found that I really hated it.

Why?

I think once I was into the semester I kind of liked it, but I begrudged the time away that it took. It’s like you get paid for the class, but there’s all the outside stuff. When you’re just out of school and applying for teaching jobs, you get the crappiest stuff, and you do this adjunct shuffle where you’re teaching at three different schools for one class and no one’s paying you very well, and you’re cobbling together this thing that, to me, wasn’t worth it. I didn’t like teaching enough to want to go down that route. And then a lot of my friends at the time got teaching jobs all over the country. And I also didn’t want to do that — I wanted to live where I wanted to live, and I didn’t want to follow a job. I had friends that ended up in Florida, Texas, Ohio, all over the country. There’s nothing wrong with that, but that just wasn’t for me. I either wanted to be in an east coast city or out here. At that time, not many people could do both. It wasn’t interesting enough to me to really sacrifice anything for it.

Yeah. I’ve gotten that sense from other people I’ve spoken to. Just teaching is so taxing that it’s really it’s own career.

Yeah, it really is. And I feel like a lot of people that are good teachers end up putting so much into it that the studio suffers because of it a little bit.

Ok, so you’re 25, you have an MFA, you’re like, “I want to be an artist.” How do you make a living at that point?

It was just sort of dumb luck. I got out of school and ended up working in a theater set design company for a little while, which was really not great. It was actually extremely unpleasant. And a friend of mine was also working there at the time and he got laid off, and then got a temp job doing web design. And this was like ’99, so it was this a great time, because everybody needed web designers. He called me up one day and said “hey, we need another guy, do you want to come work?” And he was working for this big multinational chemical company doing in house corporate web design. 40-hour week, the whole deal. More like 50-hour weeks, really. At first I was like, “I don’t want to do this, I’m not going to go work for the man!”

Did you know how to do web design?

I had dabbled in it, but I had no real idea of how it worked. But my friend was like, “just come do it.” So I agreed. I went in for an interview and I basically just lied my way through and said “yeah, I’m great, I know how to do all this stuff, it’s no problem.” Which you could do then, because no one knew anything! And they hired me, and I said “I have to give two weeks notice to my old job,” which was technically true, but I probably didn’t have to do that because that job was horrible. And in that two weeks, I taught myself how to do it. I would go work my old job during the day, and then in the evenings, I would meet my friend at the new office — he would stay late, and he showed me how it all worked. So I just sort of learned it and started full time at that job.

So suddenly you were a web designer.

Suddenly I was a full time, 50-hour a week web designer. Which, at that point, I was still so burnt from school that I wasn’t really making much art anyway. So I just decided, “I’m just gonna work and make money.”

Where was this?

This was in Philly still. The company is now owned by Dow Chemical. They’re actually this weird chemical company.

Sounds nefarious.

No. Well, OK, maybe they were nefarious, it was a chemical company, I’m sure they were up to all kinds of shit, but they’d invented plexiglas, and they made plexiglas windscreens for airplanes and bombers and stuff. It was across the street from the Liberty Bell, which was cool. I actually liked to go there. It was a cool building to work in.

So how long did you do that for?

I did that for two or three years. I’m not exactly sure. That’s what I did the rest of the time I was in Philly. And it was fine.

Was it good money?

It was good money. And Philly was so cheap then. I had my $600 apartment rent paid, no problem, whereas prior to that, it was sketchy to make rent. So it was great. I was like, yeah, sushi dinners three nights a week.

Craft beer!

Well, not in Philly. More like Yuengling.

Right. So did you quit that?

Yeah. So part of what happened was I stayed there for a while. It was great at first because you’re making a bunch of money, and like I said, I wasn’t really making much artwork anyway, I was more just keeping a diary of ideas. I feel like I went through undergrad and then I did this really intense two years of grad school where I was super invested and really productive, just a really intense time, and then I got done and I was like, “I don’t have anything else to give. I need to absorb.” So that was part of what I was doing through all that time, just sort of absorbing information and collecting images and reading things.

So then I started to feel like the interest in making artwork was coming back, and the city was getting to me. Philly, especially then, was a pretty violent place. And I’d started to get kinda Philly angry, where you’d like leave your house and put on your scowl. And I didn’t want to have that. So yeah, I went in and quit my job. Well, I didn’t exactly quit, I left on good terms, and I ended up moving to LA. But I still worked for them for a couple of years as a freelancer.

What made you move to LA?

Well, I wanted to get out of Philly first of all. There were great things about it, but I wanted go somewhere bigger. I felt like I wanted to go a city that had a really vibrant art scene, and I think the choice for me at the time was New York or LA. I’d spent a whole lot of time in NY, and I had a bunch of friends there. I’d go out and stay with people for extended periods of time to check out the scene, and it was cool, but at the same time, I took a trip out here to visit some friends I’d gone to grad school with, and I was like, yeah, this is good. I really liked a lot of the stuff that was coming out of LA. And I just thought, this is more interesting to me. It felt more livable, like you could get space, you could have the room to work. And it was really important to me to have a big space to work. I could never really understand how people started off in New York, because you’re going to be in a tiny place and you’re going to have a tiny studio, and I just didn’t want that. LA was so cheap then — or at least it seemed like it was at least. So that made my decision for me.

What year was that?

- I moved out a few months before 9/11.

So you came out and you still had some freelance work you were doing. Did you immediately start making a lot more art?

Yeah. I pretty much started into a more regular studio practice at that point. But all along I had been making all these really little things and not really showing them to anybody. And when I got to LA I started making works that I felt like I wanted to show to people. And then it got more and more important to make those for me. And I started being really excited about it.

What was the process of showing your work like?

Well, one thing I started doing when I came to LA was working for L.A. Louver. I think I started working for them in 2002.

What do you do for them?

Well, at that point, I didn’t want to do web design anymore. Because I work so much on the computer with my artwork that at the time I didn’t really want to do both. So I started working as an art handler for Louver. I was helping to hang the shows there, working for my friend Chris, and just piecing together other art handling jobs. It was really great doing that work, because I got to know all these people in the art world quickly, and I met a bunch of people that I’m still friends with now. And we’ve moved through the art world together. My friend Chris, for instance. He hired me at Louver, and I’ve now been there for 13 years. And he’s curated me in a bunch of shows, and we’ve randomly been put in shows together. There’s a bunch of people like that. It’s a good community.

To tie it back to Louver, Chris was instrumental to me being a part of the Rogue Wave show in 2005, and that was a really good thing.

A big moment.

Yeah, it launched me into a successful period of my art career. But back to what I was doing besides art. At one point Louver discovered that I could do web design, and they asked me to make some changes to their tiny little web site. So I eventually started doing that more than helping hang the shows in the gallery.

So you still work for Louver.

Yeah, that’s what I’ve been doing since then. And that’s been great. I get along with them really well. And if I’m not working for them, I’m usually working in the studio, so I’m pretty responsive when they need something.

So are you full time there?

No, it’s contract. It goes in waves. I’m not an employee, but we have this long-standing relationship. What happens is I’ll work really intensely on something for them for two or three months, and then it will go down to a fairly minimal interaction. It also varies during the year. Like September is really busy but August is really slow. It can get frustrating because right now I’m in this really intense period of work for them, and I’m really itching to get in the studio. And it’s hard to find a whole lot of time to do that. But that’s the give and take. When this project is done I’ll have plenty of time again.

So do you feel like career wise, you are comfortable with the amount of time you get to spend on your art? Do you wish you had more of it?

I wish I had more. I think anyone would say that though. I would love to just do it full time. But it’s also not a failure to not to do it full time, I think. It’s funny, I was listening to Marc Maron’s podcast with Steve Albini recently. Not that I’m a huge fan (of his music), but I know he’s done all this production work that’s amazing, and he started talking about Nirvana and producing the Pixies Surfer Rosa and all these iconic records. But in the interview he was talking about his production work, and how, for him, the production work is the day job. I thought that was really interesting. At one point he said essentially, “I’m happy to do a 40-hour week doing production, because it allows me to make whatever the hell I want in my own work.” And in my mind, I’m going, “yeah, that’s me!” You rarely hear people talk about it like that, where they’re happy to do all the stuff that’s not their first calling, as long as it allows them to do the thing they really want to do. But you know, you do get bitter sometimes, where you wish you could just do it all the time.

Yeah, well, what’s interesting about you and the parallel with Albini is probably a good one, because your full time work is still art world related. It’s not like you’re going from like, “I’m a concrete salesman” to like, “I make art at night.” Theoretically I would think that in some way there’s creative work happening in Steve Albini’s mind when he does production that feeds into his own work. I don’t know if the same is true for you because you’re not quite doing that for Louver.

I’m a little uncomfortable with you comparing me with Steve Albini.

What? Hey now, you guys are a lot alike.

Yeah, pretty much the same. (laughs)

Totally the same. But no, like you said, you’ve made a network of artists that you’ve come up with.

Yeah, I mean, I like what I do for my day job. It’s rewarding, and the problems are interesting to figure out, and I definitely don’t hate it. As far as a day job goes, it’s fantastic. I work here and I work for myself. I’m in my studio. Doesn’t mean I’m working on my own work, but I’m in there and looking at my work hanging on the wall waiting to be made. My commute from the bedroom to the coffee machine to the studio is not at all terrible.

You know, I’m not hearing a lot of angst from you about this topic.

Well, like I said before, it’d be fantastic if I could just live off the work. But I think I’m realistic about it too, in that there were moments in my career where I wasn’t really doing the day job, and that was great. But like most people in the art world, it’s a roller coaster. Even if you’re doing awesome, you could be doing really poorly in a couple of years. If you asked five year ago me that same question, I’d probably be way more bitter about it, but as I get older and still manage to make artwork, it becomes less angsty, you know? Because I’m still making the work, and I look around me and some of the people that I knew that were making work 10 years ago, or from grad school, or whatever, some of them have stopped. You can define your success in tons of different ways, and I feel like for me, success is continuing to make the work and being excited about it.

Yeah definitely. The reason I said you don’t seem to have a lot of angst about it is because from listening to you and having had a few conversations with people about this topic, you seem to have carved out a life for yourself that allows the creative work. Which in a big city like LA, or anywhere really, is no small feat. So it’s a credit to you. I think what’s remarkable about your story too is that you just from a young age, you were comfortable with wanting to be an artist, and committing to it. Me, I might have just stuck with the web design thing and said, “I’m going to be the best web designer ever.”

Yeah, it was just always sort of the thing to do. But you can be great at what you do in your day job, and also be great at what you do as your creative endeavor.

Yeah. You definitely have to think about it in less binary terms.

Yeah, I think there is a stigma of not living off of your creative work. And I think that’s kinda bullshit.

Well, I was talking to a friend recently, and he said he’d heard that before Carrie Brownstein sold Portlandia, she was working at an ad agency.

Oh really? I had no idea.

Which is so fascinating. Obviously she’d done the Sleater Kinney stuff, and she was writing for NPR at one point after they broke up, but yeah, she worked for Wieden + Kennedy for a while.

That’s unreal. Cause you do see people like that, and you think, wow, they’ve got it figured out. They’re selling records and they’re famous, they must be doing awesome.

Totally. Do you have peers or friends that make a living off their art? How common is it for people in your world?

I know a handful of people who are doing it. Certainly not the majority though. Definitely not the majority. It’s a very small minority of people who are actually doing it. A lot of people have different degrees of what the day job means. It could be like, “I work three days a month to pay my rent” or “I sold some work and then I have to do this other thing,” or whatever the combo is. Some people are doing really great. I don’t know. It seems fluid.

So, do you have any plans to change it up?

For me, the plans aren’t necessarily a change up in the day job stuff, but I’ve been working on these two or three bodies of work for a while now, and in the past couple of years, I haven’t shown them to a ton of people. And it’s really time to figure out how to figure out how to show these bodies of work. It’s so nice to just make the work and be happy with it and show it to people every now and then, but then there’s a whole other thing of putting it out to the wider world. Which is the whole point. You don’t want to create without an audience in the end. But that’s a lot of work that doesn’t come very easy to me. It’s a lot of socializing and courting that you need to do. And like I said, I’m sort of terrible at that, so that makes it more difficult. But I have been trying to make a push recently. And I need to invite more people in to come see what’s been happening in the studio. But yeah, I’m ready to do some kind of show. We’ll see.

That’s great. One last thing—tell me about what you’re doing with your cycling gear business.

So, I’ve always been a cyclist. My friend Kjeld had a company that he was running more or less as a side project and he approached me about being a part of a new version of the company. It’s called súperdomestik, which comes from a French cycling term essentially meaning right hand man. So Kjeld had this company for a while, and he decided that he really wanted to step it up and turn it into a bigger venture. So we formed a partnership, there are four of us. It’s me, Kjeld, Nic and Chris. Chris does all the photography for the business, Nic does all the design work, Kjeld is our fearless leader, and then I do all the digital stuff, so I built the website and the online shop. We make all kinds of cycling apparel, and we’re still in startup mode, but it’s going really well and it’s been really fun. We sell cycling shorts, jerseys, caps and that sort of stuff.

How do you fit that in? Is it a lot of work?

It is a fair amount of work. Or it was in the beginning because I had to build the site, but now it’s mostly updating it when we get new products in. So it’s not super intense. And it’s been really fun because it’s something that I love to do for exercise, and it’s a nice creative outlet. To do design work for my own company is fun, and to ride around town wearing my own company’s apparel is great.

Are you going to make millions off it? Become a cycling gear mogul?

Um yes, yes we are. (Laughs.) Yeah, I think it’s going to make some good money. It’s a wide open market, and we have an amazing team. So we’ll see what happens. Right now it’s just been great fun, because the guys are all my friends, and we ride bikes together. We have a pop up shop in Highland Park right now on York Blvd. So we’re selling all the stuff in there. It’s a three-month pop up through the holidays, but for me, the best part, beyond selling to people, is that we’re doing group rides out of there. So two days a week, we have a ride scheduled. People come meet at the shop for the rides. We’ll be having a few parties there too. It’s been really cool.

Yeah. It’s like a new creative endeavor/social outlet/money making enterprise.

Yeah for sure. The business doesn’t have that much to do with my creative output in the studio, but the cycling always has had something to do with it. It’s always a good way to clear my head. Or it takes me to places, like the top of a mountain, where I can photograph something that finds its way back into the artwork. I’ve actually talked about cycling in past artist statements. I did a show in 2008 where it was all this NASA archive based stuff, and I talked about how I ride my mountain bike all over the area above JPL, and you see rocket scientists hiking on the trails. And you’re looking at this mysterious group of buildings down in the valley.

Very cool. I feel like it’s rarer for a lot of artists to also to be entrepreneurs, just because that’s another really taxing endeavor.

It is. It’s definitely sucked up some time. (Laughs.) But again, if the day job is going to have to continue, it would be nice if súperdomestik becomes a bigger portion of what I do. And like I said before, I like doing it. It gives me problems to solve that I really enjoy. It’s work, but I like figuring out how to code something so it works nicely and looks the way it’s supposed to look.