“Cruising J-Town: Behind the Wheel of the Nikkei Community,” on view from July 31 through Nov. 12, chronicles the central roles Japanese Americans have played in countless car scenes throughout Southern California. Presented by the Japanese American National Museum and curated by cultural scholar and writer Oliver Wang, it will debut at Art Center College of Design’s Peter and Merle Mullin Gallery on South Arroyo Parkway in Pasadena.

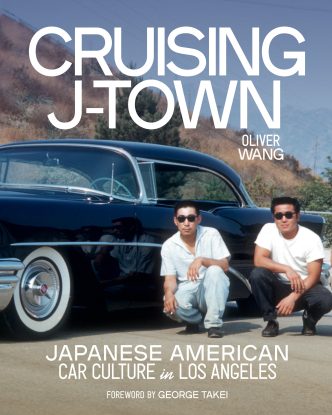

A companion book called “Cruising J-Town: Japanese American Car Culture in Los Angeles,” authored by Wang and published by Angel City Press at Los Angeles Public Library, will be released on Aug. 5. It traces the history of the Japanese American community alongside the development of the car — from the earliest days of the automobile.

Through previously untold stories, Wang, a Cal State Long Beach sociology professor, reveals how a community in a state of constant transition and growth used cars as a literal vehicle for their creativity, dreams, and quest for freedom.

In the book’s introduction, Wang writes that growing up in the San Gabriel Valley, he wasn’t much of a “car guy.” He sits down to chat about how someone who doesn’t profess a passion for cars ended up writing a book and curating an exhibition about them, what he learned from the hundreds of interviews he conducted, and what he hopes readers take away from it.

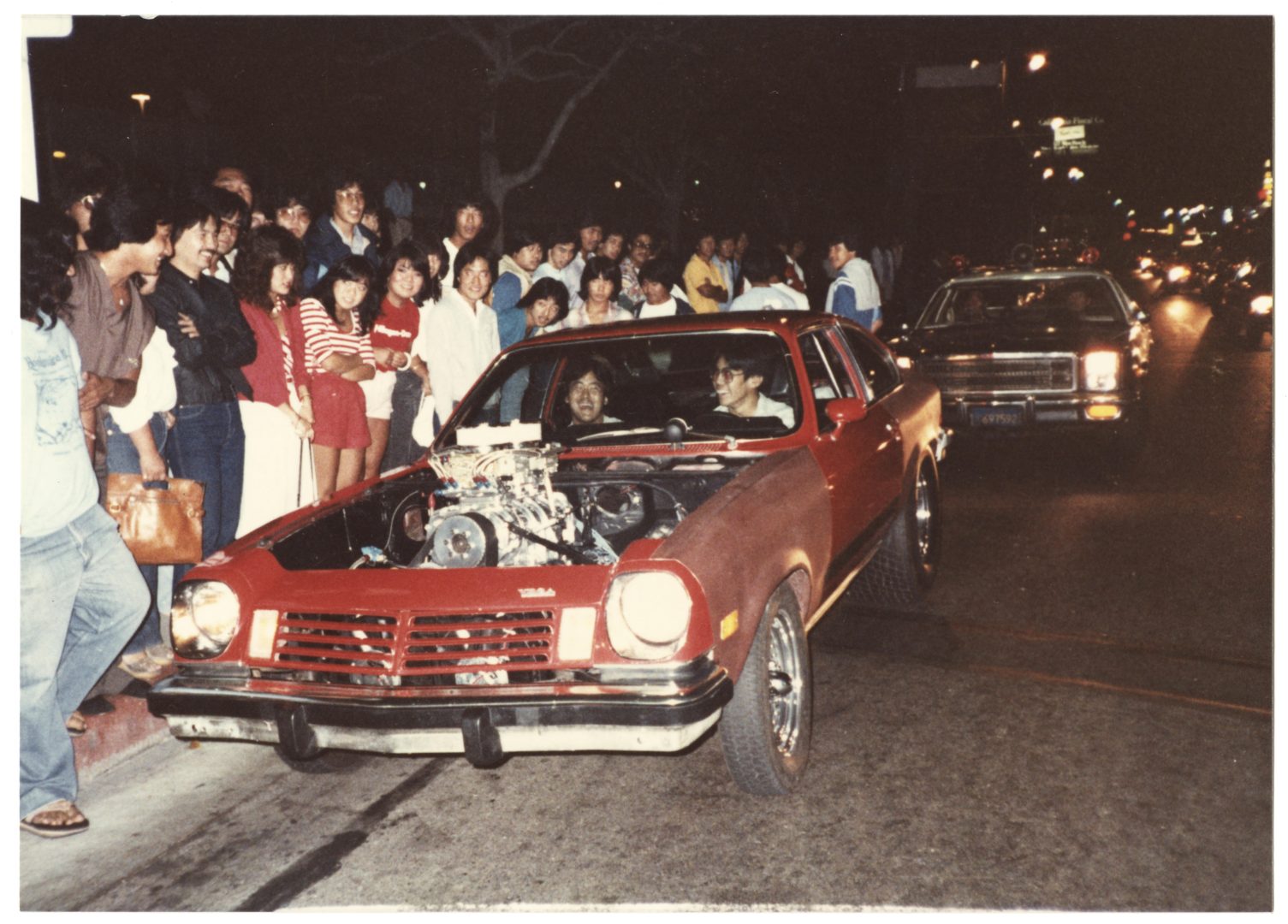

“While my personal interest revolves around music, by the time I graduated from high school in 1990, I was aware of this very popular phenomenon of young Asian Americans tricking out their cars and street racing,” Wang says. “When I went off to college and began taking Asian American Studies classes, I was already interested in the pop cultural side of the community and the ways in which Asian Americans have engaged in different forms of popular culture over the years.

“By the time the 2000s rolled around, there were articles in magazines about Asian American dynamic within the import car scene,” continues Wang. “But there was no sustained interest in it. As far as I know, none of the authors ever went on to produce anything beyond those academic articles. Part of me, maybe naively, just kept assuming that at some point someone was going to write a book about this because it seems to me — as a pop culture scholar and writer — it was such an obvious thing to focus on. It’s a pop culture activity which has such meaning for people that they invest time and money into. There are elements of ethnic identity, class, and gender.”

In 2016, Wang was having a conversation with a good friend who also came out of Asian American Studies at UC Berkeley in the 1990s. Again he lamented about the absence of books about the subject.

His friend’s reply was, “You’ve been complaining about this for 20 years, and you literally have made your career studying and writing about Asian America popular culture. If you really feel someone should be doing this work, why don’t you just go out and do it?”

That friendly challenge steered Wang toward this endeavor. At the suggestion of his wife Sharon Mizota, who is fourth-generation Japanese American, he interviewed his third-generation Japanese American father-in-law Don Mizota.

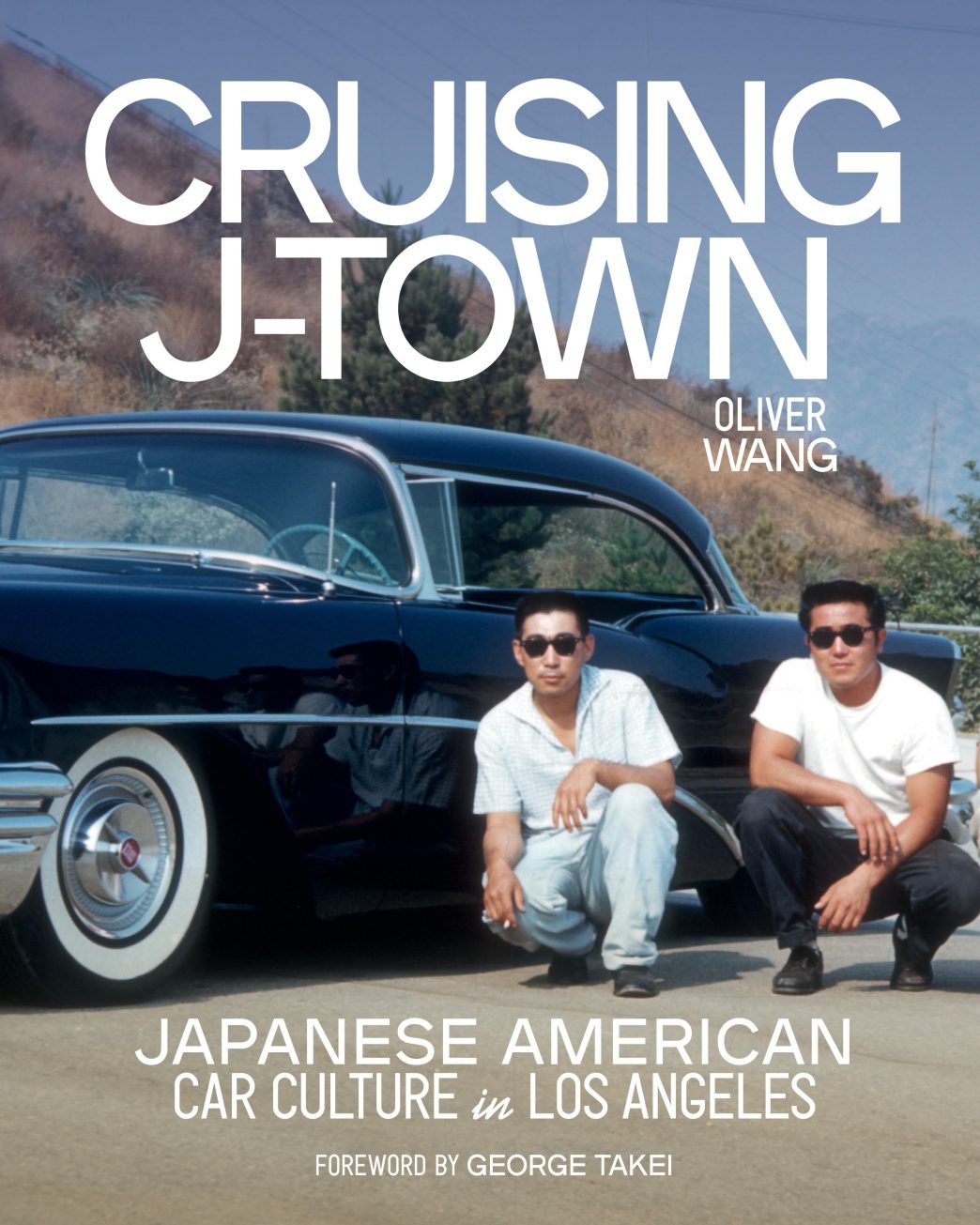

“I knew that he was into cars but I didn’t realize that when he was in high school in the San Fernando Valley in the mid- to late 1950s, he and his friends — most of whom were children of Japanese American farmers and gardeners — started a car club called ‘kame,'” Wang confesses. “The joke was that kame means turtle in Japanese because all of them had pretty slow cars.”

“It was a really fascinating interview,” enthuses Wang. “I wasn’t just learning more about my father-in-law, but also about the friends and the community that he grew up in. I then interviewed other people of his generation — Japanese Americans who would have been teenagers in the ’50s or early ’60s and were part of car clubs back then. I found examples in Mid-City and South Bay, like Gardena and Torrance. I heard about them or saw photos of those who came out of East LA and Boyle Heights.

“Clearly, there was a scene that existed then and that was what I started to explore,” Wang says further. “I wrote about some of what I had found in a relatively short article that appeared in Discover Nikkei, the Japanese American National Museum’s newsletter. I wasn’t really sure what I was going to do with the research that I was collecting. And I wasn’t entirely positive I had the bandwidth or the interest to really turn this into a book — even though I did feel strongly someone should write one.”

“In 2018, by coincidence, the museum independently came up with the idea of doing an exhibition about cars,” Wang recalls. “And because I had written that one article and they didn’t have anyone in-house that had the background to curate a show, they thought maybe I would be interested in doing it. I had a little background — I had interviewed a handful of people — but didn’t have a comprehensive knowledge of the long arc of this community’s history within the car world.

“But because I always want to leave myself open to learning new things — like curating an exhibition — and because it’s really important to me that the research I do be public-facing and not be available only to academics, an exhibition seemed like a wonderful way of solving multiple things. So I agreed to take it on.”

It was a slow project initially and Wang and his team lost a minimum of two years because of the pandemic. But in 2022, they set out to interview people in earnest.

“The exhibition and the book really began to form through all these conversations,” says Wang. “At this point I’d spoken to probably at least a hundred people about their personal histories and they were from very different areas that involve cars — not just about sport or recreation, but also very much about work, family and community.”

Asked if there was something he discovered during the seven years he was working on the project that surprised him, Wang pauses before replying, “Everything surprised me! I knew so little going in. Every new conversation expanded and opened up my awareness even more. And this was the reason to do the project — there was no book that existed from which I could learn about these things. I wouldn’t have wanted to do the project if someone had already laid out its history and the different facets.

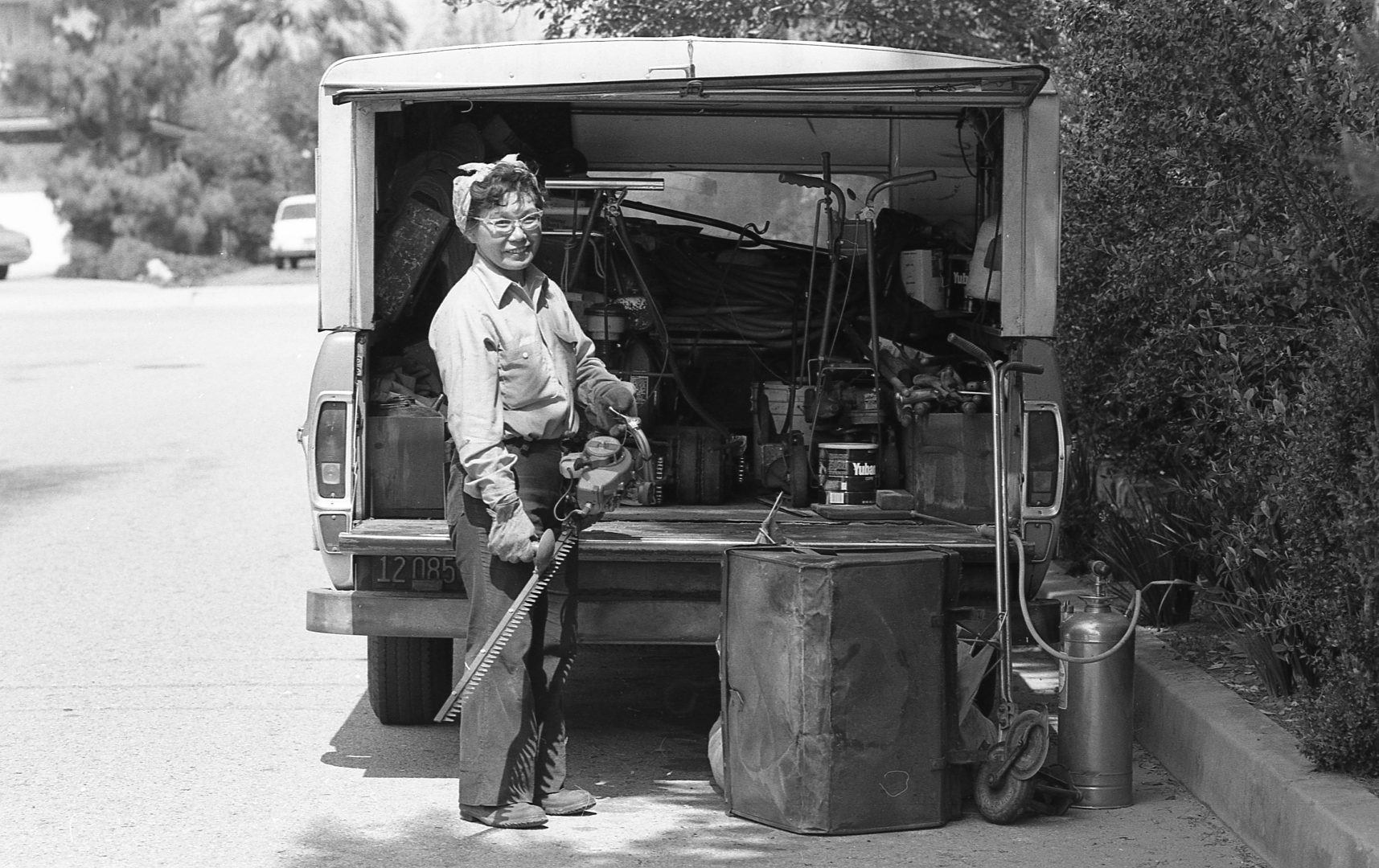

“In terms of what really stood out to me, the first thing that comes to mind would be the fish trucks,” Wang reveals. “By the late 1940s, when the Japanese American community returned to Los Angeles after being incarcerated during WWII, they didn’t have relatively easy access to food markets. They were geographically dispersed; some had moved out to Pacoima or Gardena or parts of the eastern San Gabriel Valley. The fish trucks drove all around the Southland six days a week and did door-to-door deliveries of Japanese food items — fresh fish, rice, tofu, jerky, candy. For decades the fish trucks provided this useful community service to people who didn’t have the time or the means to easily come down to Little Tokyo to do their grocery shopping.

“At some point by the early 1960s, there were enough trucks out there that the fish truck drivers organized themselves into what became known as the Los Angeles Retail Fish Association,” Wang relates. “At the same time, it was a way to prevent them from inadvertently competing against each other. And because they were now unified, they were able to negotiate better wholesale pricing.”

While Wang claims the book isn’t a complete history of the Japanese car culture in the Southland, essays from contributors cover a wide range of materials and personal anecdotes commencing with an insightful foreword by George Takei about what cars symbolize for the Nikkei community. Associate Curator Chelsea Shi-Chao Liu pens five essays: the voluntary evacuation of Japanese Americans; the concentration camps during WWII and the Japanese Americans’ return and resettlement; the fish trucks; the displacement of Japanese Americans because of freeway construction; and drift racing. Oliver Otake writes about Nikkei auto designers, Jonathan Wong discusses the import car culture of the 1900s and 2000s and Akiko Anna Iwata delves into the car audio systems business.

The book is a companion to the exhibition but it isn’t a catalog. And that’s by design. It’s a stand-alone publication that can be read and enjoyed by someone who doesn’t have an opportunity to see the exhibition.

“A conventional catalog for a museum exhibition is normally meant to be a mirror of the show,” Wang clarifies. “We could have produced a catalog, but because there hasn’t been a book on this topic before, it just made more sense to write one that provides all of these stories and the back history rather than making it strictly tied to the show in terms of format. There’s absolutely overlap between the two, but going to the exhibition is its own experience and the book is its own experience as well. The book is based on the same history and set of stories.”

Wang expounds, “The book, which is divided into four chapters, is organized loosely chronologically. We start in the early 1910s, which is not just the birth of Japanese American car culture but also of the car culture of Los Angeles. It is when access to cars and trucks becomes much more available to people. While cars have existed in the U.S. prior to that, the 1910s is when you see it become affordable to the average family. The book goes all the way through the current day, looking at very contemporary scenes like the drift racing.

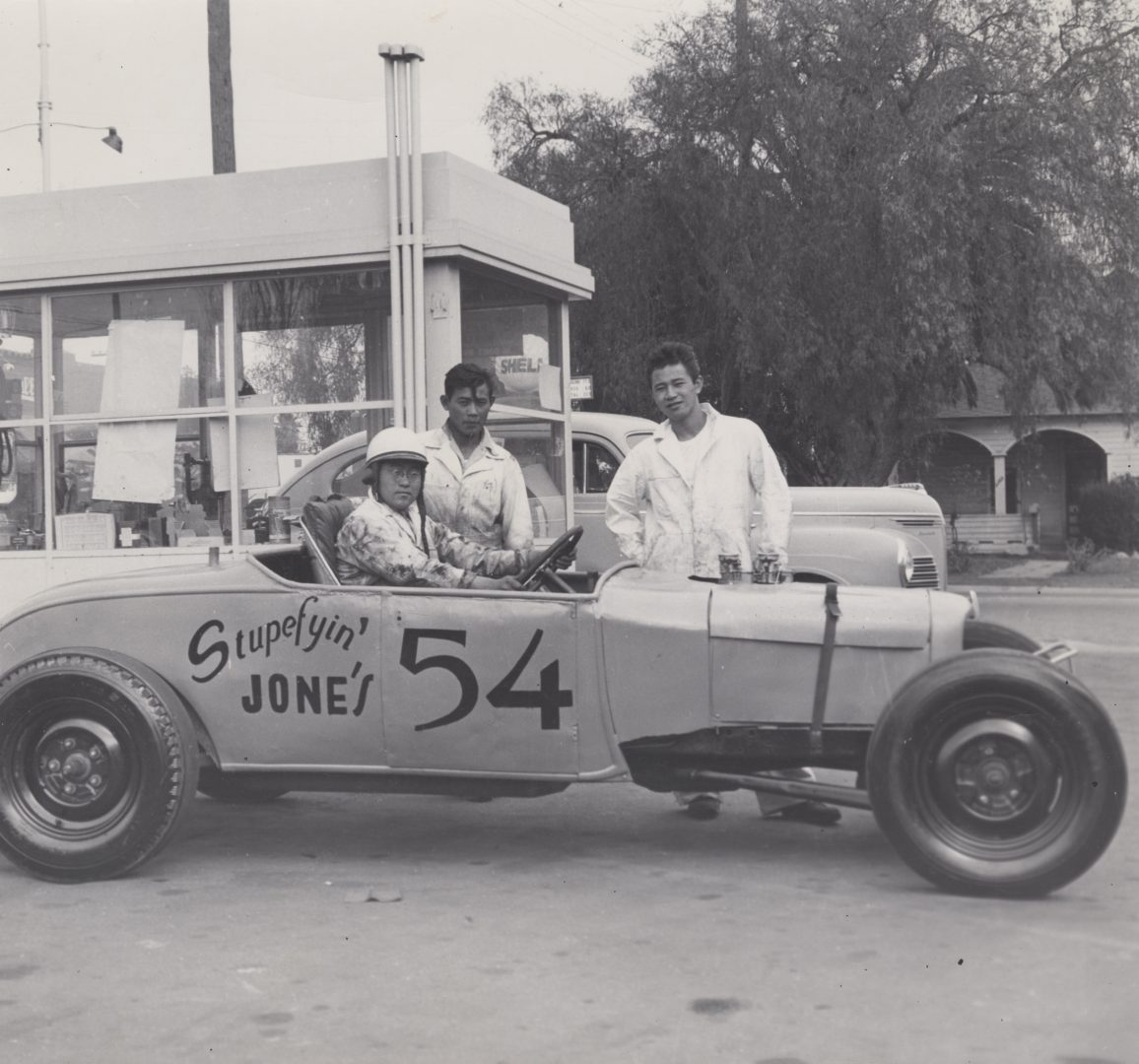

The exhibition features five cars, each of which is tied to one of those themes. For Speed, Wang and his team picked a Meteor — an early 1940s hot rod that was formerly owned by George Nakamura. The Nakamura family donated it to the Peterson Museum.

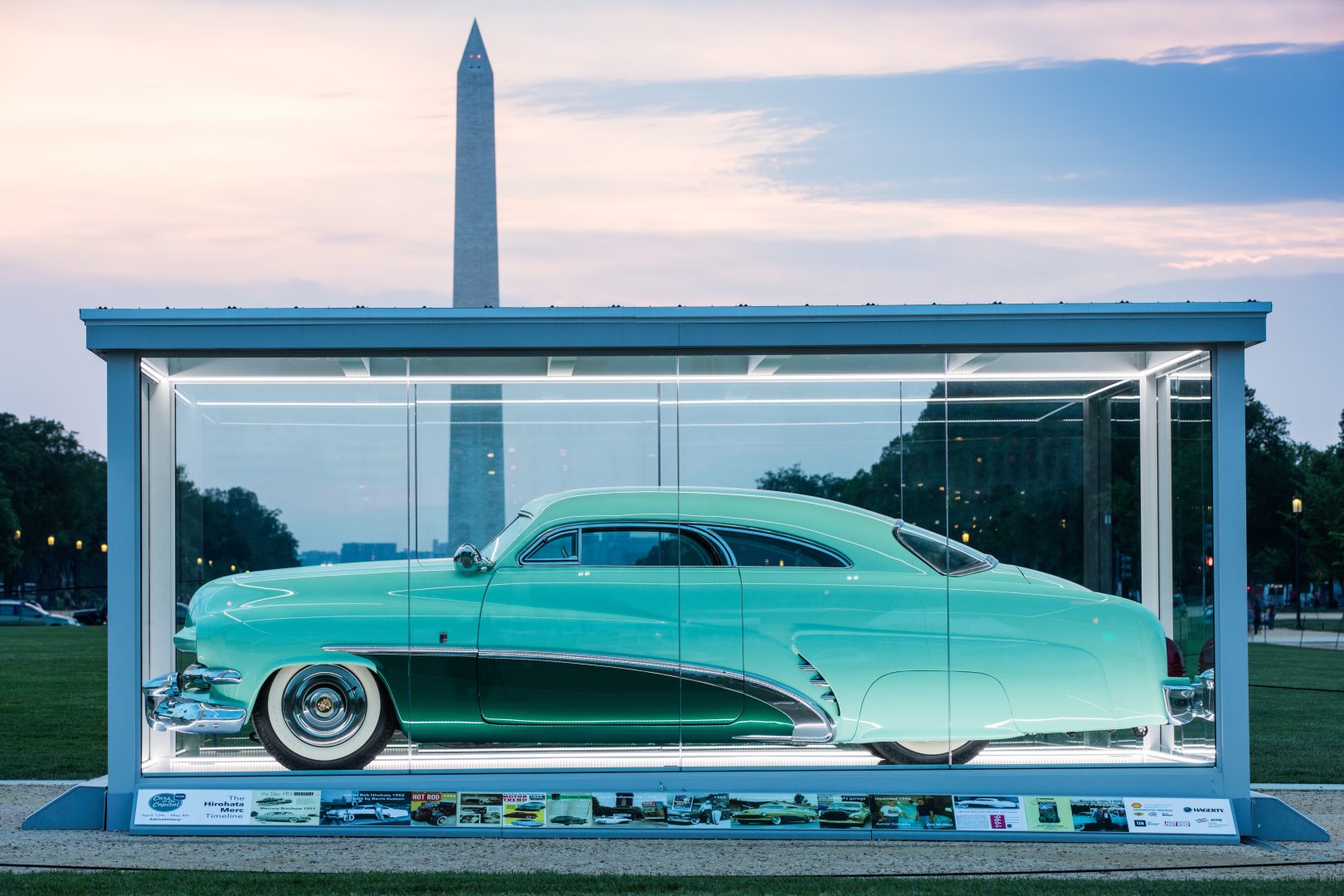

There are two cars for style: a customized 1951 Mercury coupe owned by Brian Omatsu called “Purple Reign” — a remarkable and eye-catching, show-stopping custom job; and a 1989 Nissan 240SX owned by Nadine Sachiko Hsu, who created the Drifting Pretty team when she was a pro racer in that circuit.

For work, they have a Ford F100 from 1956 — a pick-up truck that used to be driven by a landscaping professional who was known as the “hot rod gardener of West LA” because he had a muscle car engine installed in the truck

For community, the curators borrowed a 1973 Datsun 510 — the first Japanese import to really take off within the Japanese American street racing scene.

Beyond the cars, they display helmets owned and worn by former race car drivers; accessories that people would typically have installed in their cars, especially in the 1980s import scene; reproductions of archival photos; jackets from the 1950s and ’60s car clubs, as well as 1970s and ’80s racing clubs; car plaques, which are basically license plates that Japanese American car clubs embellished with their name and logo; and “thank you” gifts that gas stations and fish trucks used to give their customers.

As for the reader takeaway, Wang would like for us to appreciate how Japanese Americans have figured in the history of Los Angeles car culture.

“The world of cars and trucks has been an integral part of Japanese American lives for over a hundred years,” declares Wang. “Japanese Americans have contributed to many different aspects of car culture over that time, even if they have not been widely recognized for it. They were there, not just in the background but very much in the foreground. These hidden or forgotten mysteries, as you might call them, are there waiting to be discovered and shared.”

Furthermore, Wang wants to emphasize the subject of the “Cruising J-Town” book and exhibition.

“I encountered quite a few people who think the project is about the history of how Toyota and Honda came to the U.S.,” says Wang. “I usually have to just very gently correct them and say this isn’t a show about cars and car brands; it’s first and foremost, about a community of people and their relationship to cars and trucks. The people in the community are at the center of it; cars help tell their stories but the cars are not the focus.”

“The irony is, I think people assume that it’s about Japanese car brands because Japanese cars have become such an important part of the American car landscape,” Wang stresses. “And I think the Japanese American community — in its own small but significant way — helped contribute to how Japanese imports were able to get legitimized and become respected within the American car world.”

After the exhibition opens and his book is released, Wang will have the time to work on his next endeavor. He has several projects on the back burner and has already done the research about how New Order’s “Bizarre Love Triangle” became the unofficial anthem for Asian American Gen Xers. There’s one project that he and a research partner have been discussing about inter-ethnic marriages; and there’s a podcast idea that he wants to get back to called “Songs for Ourselves,” the conceit for which he says is drawn from the fact that for most Asian Americans growing up in America, their favorite songs were by people from other communities.

But that’s all in the future. For now, Wang has given us the “Cruising J-Town” book and exhibition to peruse and take in. And one doesn’t have to be a car aficionado or Asian American to find the stories they tell to be illuminating and uplifting.