Polyester is everywhere, from that beautiful forest-green waterproof parka to that soft, silky lingerie. Gone are the days when the material got a bad rap for being rough and uncomfortable. A quick look at garment tags often reveals telltale hints of fashion’s best open secret for a low-cost, multipurpose textile. But what’s the environmental cost of the prevalence of this plastic-based fabric and other inexpensive fabrics often used by fast fashion brands?

The RealReal used data from Textile Exchange to explore the far-reaching prevalence of polyester, including in the fast fashion industry.

Fast fashion is a clothing production model that enables consumers to buy affordable garments just two weeks after their design rather than months. Instead of two major seasons — spring/summer and fall/winter — fashion brands can churn out new designs in as many as 50 to 100 microseasons. Companies like Zara, Shein, H&M, Forever 21, Uniqlo and Boohoo optimize resources by minimizing costs on labor, textiles and marketing.

Spanish fashion giant Inditex — the parent company of Zara, Bershka, Pull&Bear and other brands — is credited with pioneering this rapid production and sales process. However, the race to continually streamline production processes for increased profits goes as far back as the Industrial Revolution. Amancio Ortega, Inditex’s founder, simply perfected it.

At first glance, fast fashion appears to be a win-win situation: Style mavens can constantly sport the latest trends without breaking the bank, while retailers enjoy continuous sales. However, this breakneck production and development has a dark side.

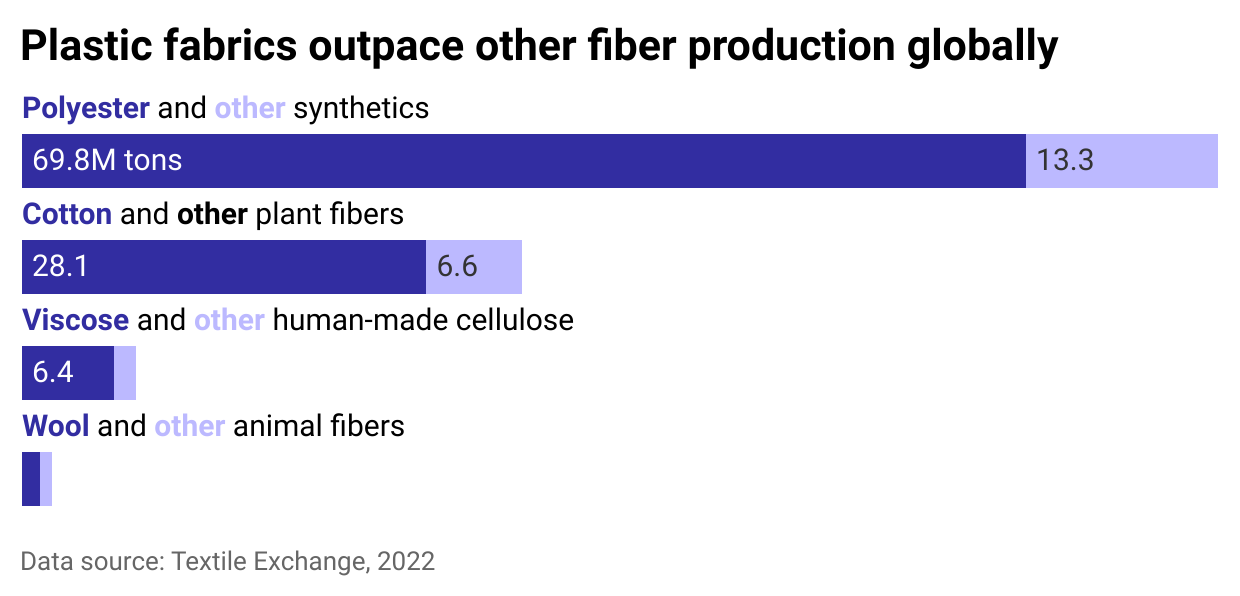

Synthetics dominate fiber global fiber production

Polyester alone accounted for 54% of global fiber production in 2022, according to Textile Exchange; combined with other synthetic fibers, that figure jumps to about 65%. These fibers are ubiquitous in seat belts, carpets, sportswear, shoes, hats, curtains and bedsheets, to name a few. And there’s a reason why.

Synthetic fibers like these seem to be miracle fabrics. They are often much easier to care for and maintain. They keep their shape, better resist stains and can be washed at lower temperatures.

Unlike natural fibers that begin with cultivation and harvesting plants, synthetic fibers are made from petroleum products through easily replicable chemical processes. This means better, more reliable raw materials and lower costs for manufacturers and consumers. In short, this plastic material fits the demands of modern life to a T.

A ‘plastic fantastic’ evolution

Synthetic fibers have evolved significantly since their initial development nearly a century ago in the DuPont laboratory. It was first created in the 1930s by Wallace Hume Carothers and a team of young chemists. This group would eventually be better known for inventing nylon, but not before making inroads into other chemically based fabrics.

Development moved across the Atlantic around World War II, when British chemists John Rex Whinfield and James Tennant Dickson, who worked at Calico Printers’ Association in Manchester, patented “polyethylene terephthalate.” With the help of inventors W.K. Birtwhistle and C.G. Ritchie, British scientists gave the world Terylene, or polyethylene terephthalate, the first textile made from polyester fibers. DuPont’s Dacron soon followed.

The 1960s was the age of “plastic fantastic.” Manufactured fibers rapidly became the textile of choice for the clothing industry. Its ease of care and versatility dovetailed with the postwar boom and the feminist movement.

Concerns about synthetic fibers first arose in the 1970s, amid wars in the Middle East and growing environmental consciousness — and it wouldn’t be the last.

The arrival of fast fashion in the 1990s made the question of synthetic fiber sustainability more urgent. While polyester can make durable, long-lasting items like medical equipment and prosthetics, its use in large-scale clothing production is ecologically unsustainable.

Polyester production consumes vast amounts of water — though surprisingly not as much as natural fibers. Laundering clothes from these plastic fabrics also releases microplastics that harm marine life. In 2020, U.K. scientists found up to 1.9 million pieces of plastic in about 10 square feet of the Mediterranean Sea.

The European Environment Agency estimates anywhere between 200,000 and 500,000 tonnes of microplastics from synthetic fabrics are released into waterways from factories and home washing machines each year, severely polluting marine environments. Once thrown away, synthetic fabrics also take a long time to degrade — up to a century, by some estimates.

Systemic and personal solutions to the fashion question

The fashion industry’s environmental impact has been so prominent that the United Nations established the Alliance for Sustainable Fashion in 2019. Efforts to reduce the clothing industry’s carbon footprint cover the entire life cycle of fashion, from producing raw materials to manufacturing, distribution, consumption and disposal.

Growing consciousness around polyester’s sustainability has increased momentum for finding more environmentally friendly alternatives, such as recycled polyester. Still, recycled polyester only accounts for 14% of polyester production.

Household items, plastic bottles, straws and other synthetic waste can be melted down to create raw material that is then transformed into polyester yarn for textiles. In 2021, Textile Exchange launched the 2025 Recycled Polyester Challenge, inviting companies to use at least 45% recycled polyester in their products by 2025.

These initiatives are a good sign, but they still do not solve the issue. Even after polyester is recycled, the final clothing product becomes more difficult to recycle again because of the complex process involved in recycling mixed materials and dyed garments.

Apart from systemic solutions offered by large organizations like the U.N. and Textile Exchange, consumers can also participate in the change. The environmental toll of fast fashion’s lightning-fast production cycle is especially alarming because of the consumer behavior associated with it.

According to McKinsey, clothing production doubled from 2000 to 2014, with people purchasing 60% more clothes than before. McKinsey also noted that clothes are thrown away in as little as seven wears, and for every five pieces of clothing produced, about three end up in a landfill or incinerated yearly.

Faced with new, eye-catching designs every few weeks, the challenge for the environmentally and sartorially savvy is to resist the temptation of retail therapy and to extend the life of the clothing they own: a plastic fantastic challenge, indeed.

Written by Martha Sandoval. Data work by Wade Zhou. Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on The RealReal and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio. The article was copy edited from its original version.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.