From Dec. 2 through Mach 18, “Art for the People: WPA-Era Paintings from the Dijkstra Collection” will be on view in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art at The Huntington. Featuring 19 remarkable works drawn from the collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra, the exhibition is a collaboration between the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, the Oceanside Museum of Art in Oceanside, and The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino.

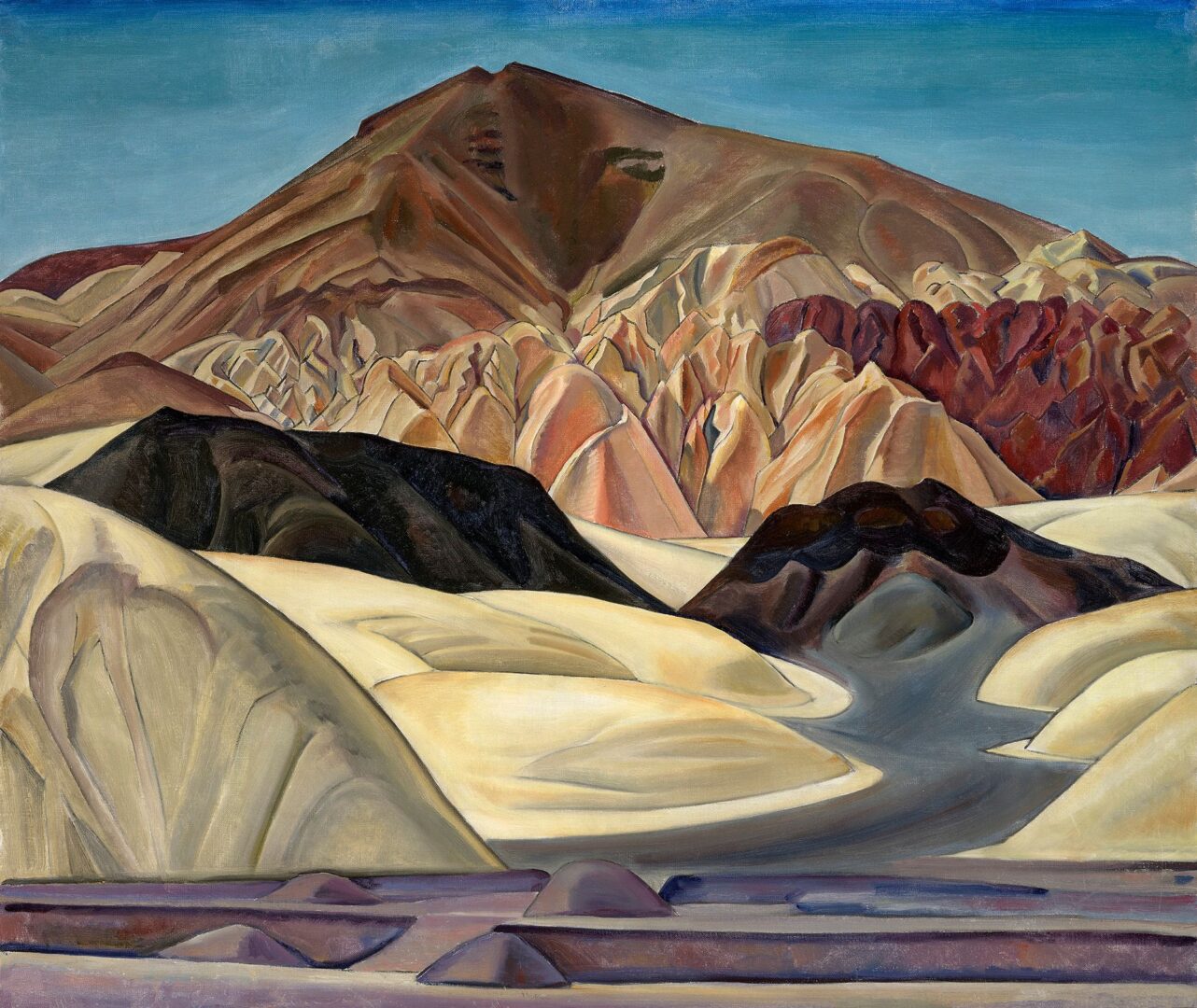

The exhibition highlights federal Works Progress Administration artists of the 1930s and early 1940s who were employed by the government to help stimulate the post-Depression economy. More than 10,000 artists participated, creating works that represented the nation and its people, and seeking to express fundamental human concerns, basic democratic principles, and the plight of the dispossessed.

“Art for the People” and its companion catalog feature paintings from across the United States, with strong representation by California artists, artists of color, women artists, and Jewish artists who have generally been omitted from the WPA-era narrative. Some of the paintings are often described as American Expressionism or American Scene, depicting both urban and rural subjects and focusing on the lives of average Americans.

The Huntington’s presentation of “Art for the People” is the third and last stop for the traveling exhibition, which originated at the Crocker Art Museum, where it ran from Jan. 29 to May 7, 2023. It was on view at the Oceanside Museum of Art from June 24 until Nov. 5. Shown differently at each venue, the installation at The Huntington showcases paintings by 18 artists, including paintings that were given to The Huntington by the Dijkstras, such as “Soldier,” a major work by African American artist Charles White. White, who became an important figure in what was known as the Chicago Black Renaissance, made the painting in 1944 after he had been drafted into the U.S. Army.

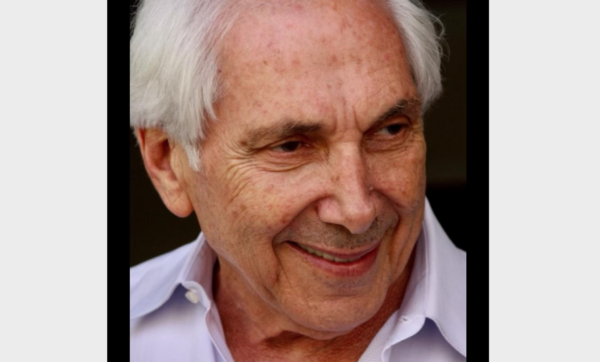

Dennis Carr, Virginia Steele Scott chief curator of American Art at The Huntington, speaks to me about the exhibition and how the collaboration with the two other museums came about.

“If memory serves, it started with a conversation between Scott Shields at the Crocker Museum and Sandy and Bram Dijsktra, who expressed their interest in presenting publicly this part of their collections,” Carr starts. “Once the Crocker Museum was enthusiastic about it, they reached out to other venues, including The Huntington. We were especially interested given the strength of our American paintings collection in the early 20th century — specifically around the WPA period — as well as the strength of The Huntington Library in collecting material like this. So we felt it was a natural fit for the institution.”

Carr explains, “Both the Oceanside Museum and the Crocker Museum displayed all 40 paintings. We didn’t have the space available at The Huntington but we chose what we felt were highlights of the collection and focusing on California artists, artists of color, and women artists.”

“There’s one from The Huntington’s permanent collection which was donated by Bram and Sandy Dijkstra in 2013,” Carr continues, referring to ‘Soldier’ by White. “In my opinion, it’s one of the most striking paintings in the American Art collection. White was a black artist who moved from the East Coast and eventually settled in Altadena and became a very important painter in Los Angeles in the mid-20th century. This is a vital early work by him and we’re so proud to have it in The Huntington’s permanent collection. But we thought it was important to include the Charles White painting in this show because it’s of the era and it’s by a very local artist. It’s been on view in our gallery ever since they donated it in 2013 and it’s nice to see it join other works from the Dijkstra’s private collection in the exhibition.”

Carr adds, “Miki Hayakawa was a Japanese-born artist who immigrated to California as a young girl and there’s a delightful painting by her called ‘The View from my Window’ from 1935. It shows the scene from her apartment in San Francisco looking at Coit Tower in the distance. There’s also a painting by Sueo Serisawa, another Japanese-born artist who lived in California during World War II but had to leave the Coast and eventually settled in Chicago and New York. The work that’s represented in the show is from 1945. There are works by other women artists like Helen Forbes who depicted a wonderful aspect of the California landscape.”

“What the exhibition shows is not just an East Coast view of art in the period but across the United States and the development of different regional schools on the East Coast, in the Midwest and on the West Coast — where different artists were showing different aspects of American life. The focus of the Dijkstra collection on mostly underrepresented and under-recognized artists presents a much broader and more diverse vision of this era,” Carr emphasizes.

Interestingly, while “Art for the People” is on view, The Huntington will be opening a show in February about Sargent Claude Johnson, another WPA-era painter.

“Sargent Claude Johnson was a black sculptor based in the Bay Area who was also supported by the WPA in the 1930s and early 1940s,” says Carr. “I believe he was one of only three black supervisors of the WPA nationwide. He was a very distinguished artist and was very proud of the fact that he was a supervisor in the WPA. He led large-scale projects for architectural installations in a number of venues in San Francisco and Berkeley. For Johnson, the WPA allowed him to work on a bigger scale with larger teams of artists. It definitely supported him as an artist during a difficult time and I think it allowed him to expand his creativity.”

I ask what the significance of WPA-era paintings in American art is, and Carr replies, “They present a very diverse look at the American scene in two extremely important decades in the development of American art — the 1930s and 1940s. It was a very challenging time for artists, financially and socially, but it was also a time of significant governmental support for the arts. It kept many of them alive and working, and it allowed many artists to work on a larger scale than they had ever before. Likewise, it was a time of great flourishing of the arts in the United States and the seed for that was planted not just by the government but by the people who participated in this program. That resulted in a number of murals created for post offices, government buildings, and public spaces like schools and classrooms. It also produced a larger network of artists who were also being supported by the program and I think that it helped the advancement of communities of artists across the United States.”

As for the visitor takeaway, Carr opines, “It’s a profound and striking view of a bleak period in American history and it looks at ways that visual artists were responding to this moment across the United States. I think there will be many names of artists that our public is not familiar with but should be, because the works are stunning and powerful, and they speak with the clarity and an emotional quality that really capture the era. Sometimes art can feel esoteric to some audiences, but this art speaks with the simplicity and directness that people can relate to. I think that the show itself and the works within it will be a surprise for many.”

“Moreover, it’s interesting to look back in an era when there was the largest governmental program for the support of the arts ever created until then or since. We can reflect on what that meant in that moment and how the arts remained so relevant in American culture and what the government’s role could be or should be to support that,” Carr concludes.