By Mark Olalde

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

The California Legislature recently passed a bill that would provide the state’s taxpayers some of the strongest protections in the nation against having to pay for the cleanup of orphaned oil and gas wells. But Gov. Gavin Newsom has not indicated if he will sign it.

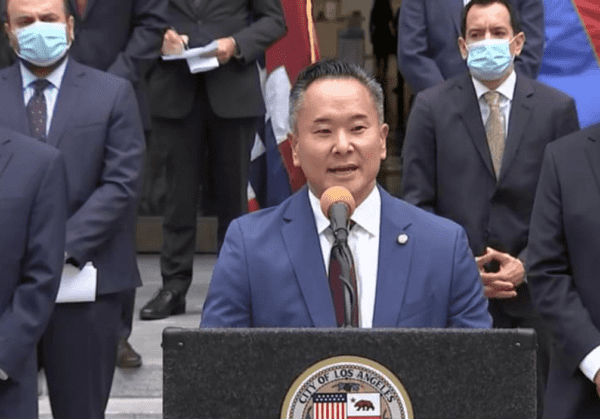

AB1167 would require companies that purchase idle or low-producing wells — those at high risk of being left to the state — to set aside enough money to cover the entire cost of cleanup. Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, a Los Angeles Democrat who authored the bill with the support of the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environment California, said it’s needed to “stem the tide” of orphaned wells.

Newsom has until Oct. 14 to make a decision. A spokesperson declined to comment, saying the governor would evaluate the bill “on its merits.” The state’s Department of Finance released a two-page analysis opposing it.

It costs more than $180,000 to clean up an average orphan well in California, the state told the U.S. Department of the Interior in 2021, according to documents ProPublica obtained via a public records request. This includes plugging the well with cement, removing aboveground infrastructure like pumpjacks and decontaminating the site. But bonds, which are financial instruments guaranteeing to pay for cleanup, cover only a tiny fraction of that cost. A ProPublica analysis of state data found that oil and gas companies have set aside only about $2,400 per well. (State oil regulators are currently reevaluating companies’ bonds to increase them within existing law, which does not mandate that they cover the entire cleanup cost.)

Left unplugged, many wells leak climate-warming methane, brine and toxins that were used in the drilling process.

“It’s a setup for disaster,” said Ann Alexander, a Natural Resources Defense Council senior attorney.

The bill follows ProPublica’s reporting on the exodus of oil majors from the state’s declining industry — one sale last year saw more than 23,000 wells move from Shell and ExxonMobil to a little-known German asset management group called IKAV — and on the multibillion-dollar cost to clean up the industry. ProPublica’s work was repeatedly cited by the Legislature and the bill’s supporters.

Despite its green reputation, California has a long history of weak oversight of its oil and gas industry, which has left behind an estimated 5,300 orphaned wells. Many are scattered across Los Angeles, complicating redevelopment. Others spew methane in Kern County’s huge oilfields.

Companies have little incentive to plug wells; it’s cheaper to sell or to walk away and forfeit the small bonds currently required by the state.

“It’s too easy for them right now to offload those unproductive oil wells to newer or less-resourced companies that may turn around and go bankrupt and that don’t have the adequate financial capacity to do the job of cleaning up,” said Laura Deehan, director of Environment California.

The Western States Petroleum Association and California Independent Petroleum Association industry trade groups warned state lawmakers that “this misguided bill will increase the number of orphan oil wells in California.” The organizations argued that requiring bonds that cover the full cleanup cost would dissuade sales to companies hoping to enter the market. This, in turn, could lead to well owners getting stuck with the expensive cleanup, causing insolvency and ultimately leaving the wells with the state.

Dwayne Purvis is a petroleum reservoir engineer who authored a study that estimated it would cost as much as $21.5 billion to clean up California’s oil industry. He pointed out that the most common type of bond — a surety policy — is similar to insurance guaranteeing a well will be plugged, so oil companies wouldn’t have to set aside the full cleanup cost in cash to comply with AB1167. Federal regulators recently found these bonds are relatively cheap.

If that stops companies from buying wells in California, Purvis said, then there’s a bigger problem: “This admits — implicitly but almost inescapably — that the cost of plugging exceeds the value of remaining production,” he told ProPublica via email.

A Western States Petroleum Association spokesperson did not address questions about its claims. The California Independent Petroleum Association did not respond to requests for comment.

In negotiations over the bill, according to people present, the trade associations pointed to one example in particular to highlight why the legislation would create more orphan wells — the sales of some of the more than 750 wells orphaned following bankruptcy filings by multiple entities in the Greka group of companies. The sales, the industry argued, presented an opportunity for the wells to be plugged by an oil company, not the state.

However, hundreds of the wells remain on the orphaned list to this day, only they’re now associated with a new company: Team Operating.

Greka’s CEO and Team Operating didn’t respond to emails requesting comment.

The bill does carry a potential loophole, experts cautioned: whether the increased bond requirements in the bill would apply to wells transferred through shell companies, as is often the case.

The state Department of Finance’s opposition to the bill relied on three arguments.

The agency’s report claimed that large companies with enough resources to plug wells are coming into the California market. But research shows these producers are exiting the state and handing off their aging, unprofitable wells to smaller companies that are less likely to be able to afford cleanup.

Its analysis also suggested that bond underwriting companies are “becoming hesitant” to do business in California. Purvis said that if these companies believe the situation is too risky to guarantee cleanup costs will be paid, “then the taxpayers of California probably should not extend producers the same credit.”

Finally, the report argued the bill is unnecessary because California regulators already have the authority to recoup plugging costs from wells’ previous owners.

While existing law gives the state this authority, it only applies to wells transferred after Jan. 1, 1996. Oil drilling in California dates back to the 1860s, and many thousands of wells were sold prior to the law’s cutoff, meaning the state can’t go after the wells’ former operators.

ProPublica reviewed the state’s list of orphaned wells and found numerous examples of well cleanups being left to taxpayers despite the wells being sold after 1996. In those cases, the state either hasn’t used its authority or has otherwise failed to secure plugging funds.

Department of Finance analysts referred questions to the state’s oil regulators, who were the source for much of the report. A spokesperson for the California Geologic Energy Management Division said state regulators have obtained money from previous owners on occasion.

But going after older operators is difficult, said Rob Schuwerk, a former New York assistant attorney general and the North American executive director of the energy finance think tank Carbon Tracker Initiative, and bonds are guaranteed money.

“There’s no better substitute for having the cash,” he said.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox. Republished with Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).