Does the term “Asian American” do more to include or exclude the many cultures that fall under it?

How valuable is the increased Asian American inclusion in media to everyday Asians—is that representation meaningful enough?

What does it mean to be American? Who has the right to wear that title and to share fully in the promise it implies?

These are the questions that Simon Li prefaced the Huntington’s Asian American Experiences in California symposium on March 4, 2023. I was only able to attend the first and last panels, missing out on the “present,” so the anecdotes I highlight below are only from those panels. However, you can watch all three panels on the Huntington’s website here.

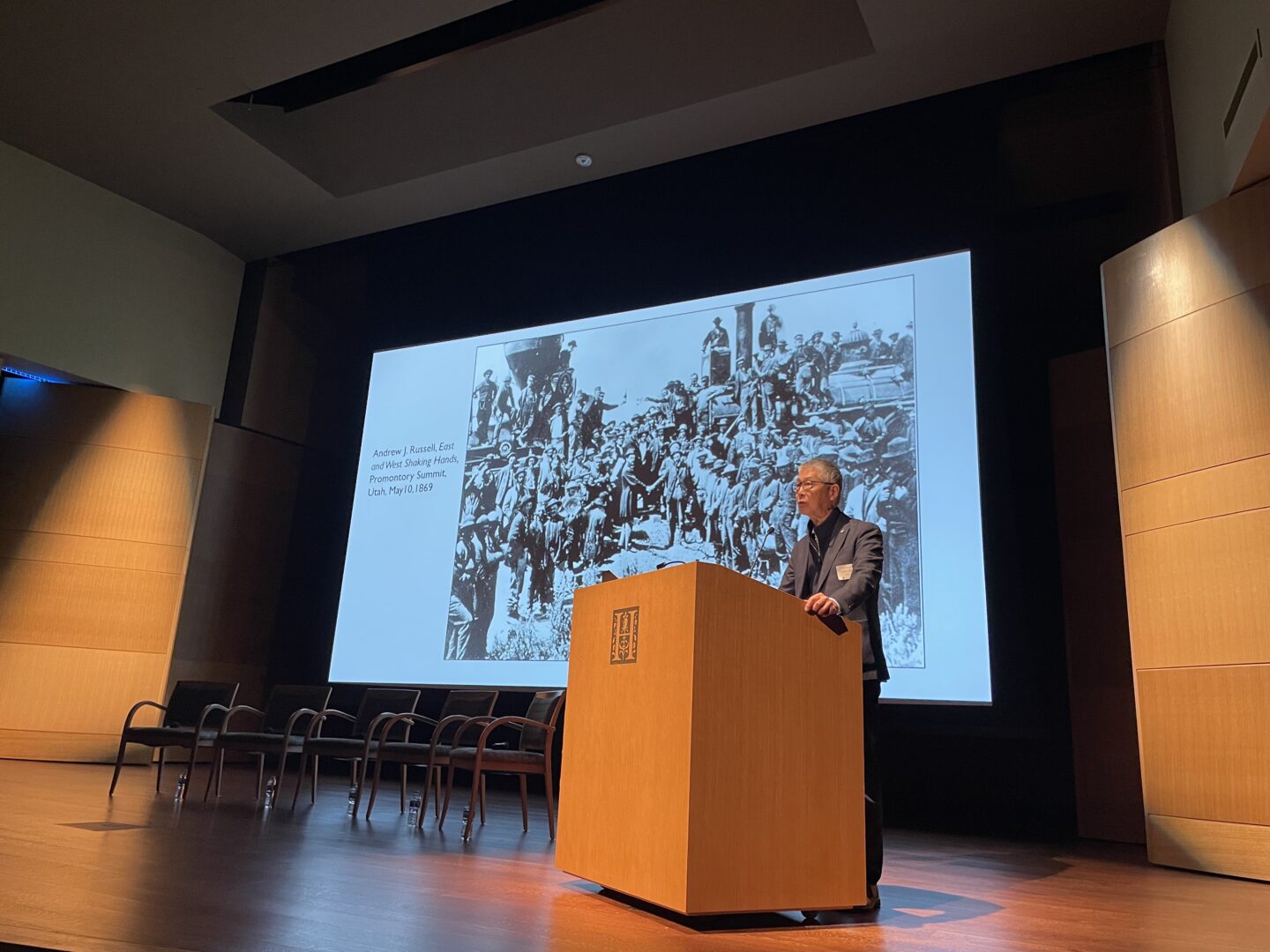

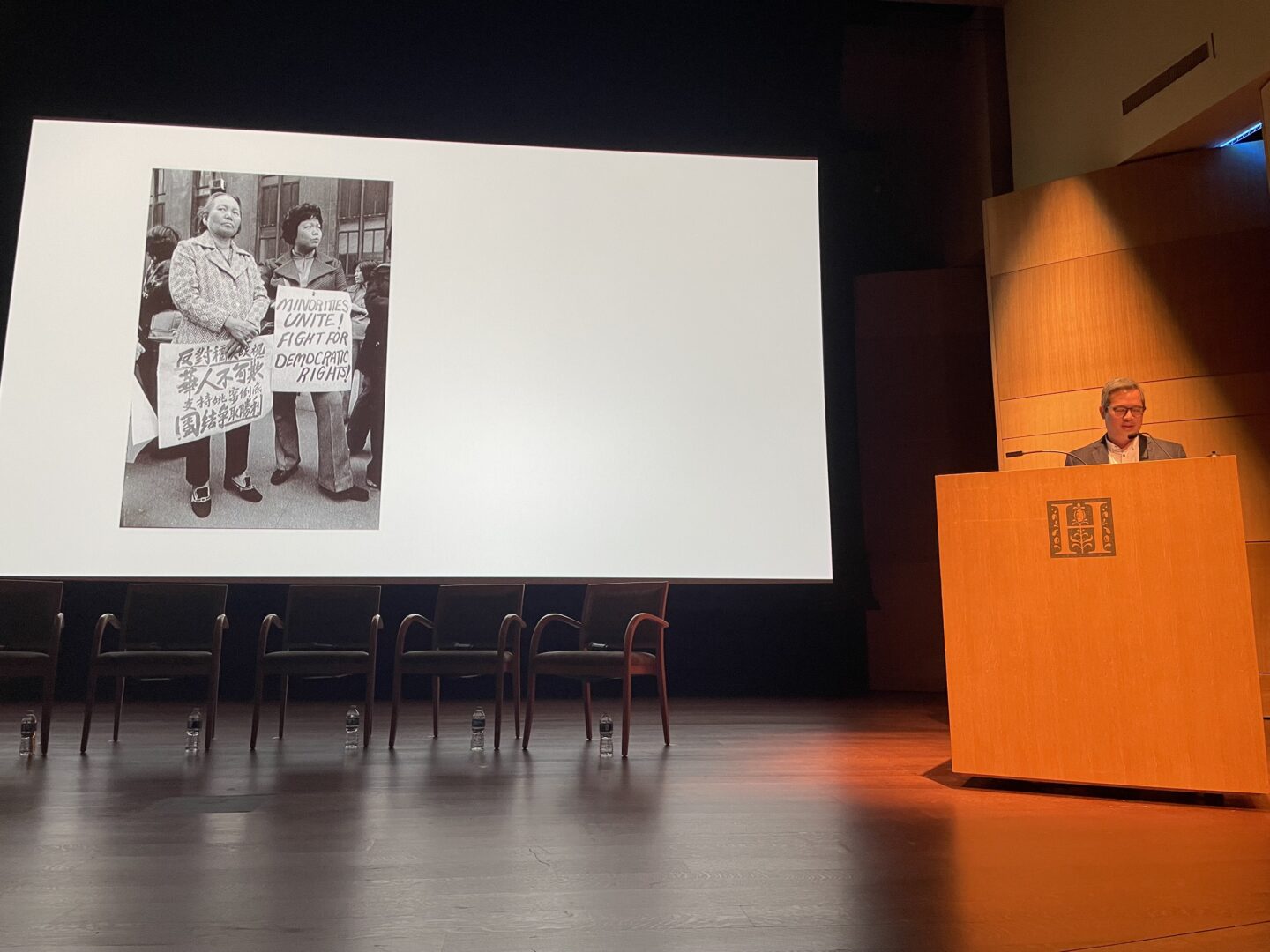

During the “past” panel, each speaker reoriented—every pun intended—the current framing of Asian American history. In examining the history of Chinese Americans and their role in building the railroads across America, Professor Gordon Chang featured a photo entitled “East and West Shaking Hands.” At first glance, it’s nearly impossible to see any Chinese individuals in the photo at all; the lone Chinese worker, in tattered worker’s garb, was captured with his back facing the camera. Most importantly, he was captured mid-movement, blurry and literally out of focus: the perfect metaphor for the lack of focus on the role of Chinese workers in this grueling feat of transportation they were instrumental in completing. Writer Jean Chen Ho examined the flawed, skewed history of the 1871 LA Chinatown massacre. The most prominently known story of the event submits that a duel between two Chinese men from rival tongs caught a white rancher in their crossfire. This death spurred a predominantly white “vigilance” party to consequently murder dozens of mostly uninvolved Chinese people in the process of purportedly attempting to save them. In this story, the conventional narrative blamed the Chinese community for the very violence they suffered. Writer Naomi Hirahara walked us through the Japanese businesses and community members of Pasadena pre-World War II, and asked us to imagine with her what the town would have looked like had Japanese internment not happened. And amongst the many pieces Art History Assistant Professor Marci Kwon presented, a personal standout was a piece inspired by the “I am an American” sign that a Japanese grocery in Oakland erected on their storefront following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Contemporary Filipina artist Stephanie Syjuco took that historical image and reframed the statement as a fabric banner, in which she compacts the letters comprising “American,” asking viewers to contemplate what being an “American” means to them.

Each speaker highlighted an incomplete, overlooked, or undervalued narrative of Asian life in America—delving into the history we have, the Eurocentric perspective from which it was written, and how we might fill in the gaps of our own history. In answer to my question about why we should look to the past and what value we can take from re-evaluating it, Professor Chang eloquently stated that this work helps to reframe American history, properly acknowledging our centrality in the story of the creation of what is currently referred to as “America.”

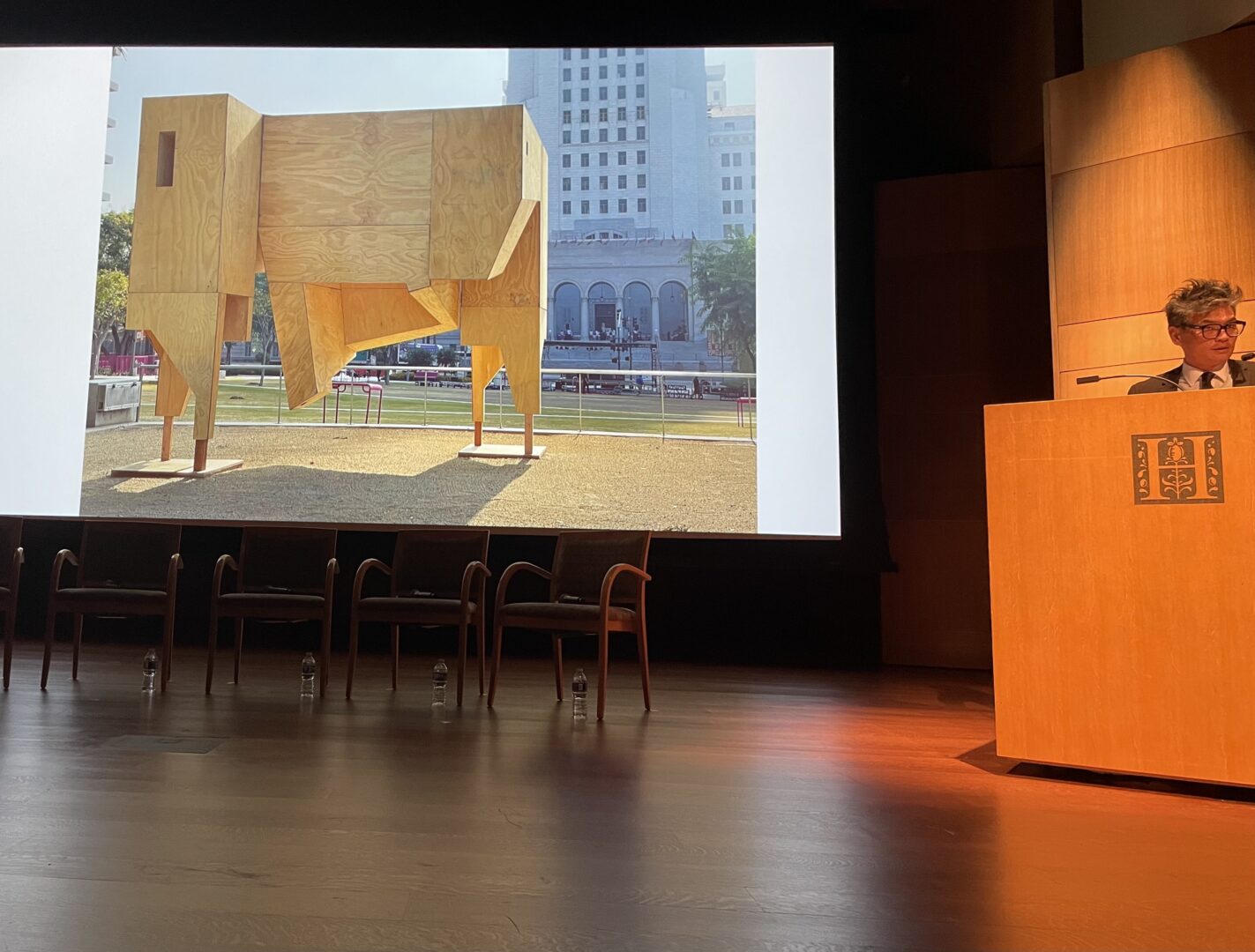

In the “Future” panel, each speaker presented a provocation to the audience regarding how we might envision the future of Asians in America. Stop AAPI Hate co-founder Manjusha Kulkarni made the provocation that our fear and anger as a collective group of many different Asians in America drives us towards increased civic engagement, and hopefully in turn, improving outcomes, legislation, and representations of Asians in politics. Lawyer Karin Wang asked us to acknowledge the privileges the Asian American community has and consider how we might use that power to uplift others, especially other communities of color. Artist Jimenez Lai shared and described an installation he had created, in which visitors could whisper their fears, and hear them return as a distorted version of that sound. This piece stood out to me as a reminder to acknowledge our fears for the dissonance and distortions of the truth that they are, and to take the space to reimagine our world in ways that don’t currently exist. Writer Jeff Chang brought us home by prompting us to consider the future Asian American community we envision and how we build a future community that endures.

For my part, the answer to Li’s first two questions is clear. Yes, the term Asian American continues to hold merit. Li acknowledged in his own remarks that others outside our Asian community will not bother to harbor distinctions between Chinese American or Japanese American, as in the case of Vincent Chin. Instead, we have, are, and will likely continue to be ‘categorized’ by our overarching heritage: Asian. Thus, we do share common experiences here in America even as we uphold and celebrate our many distinct cultural traditions. However, we can incorporate both the collectivism of our heritages and the individualism touted by America: as Asians in America, we can uplift and still celebrate our individual, unique heritages, under a broader, joyful community of Asian American. More diverse and widespread Asian American representation, in every space and circumstance, matters. Hearing from voices and experiences from across the wide diversity of Asians in America matters tremendously: we cannot know the experiences of others, nor help them, if they are not present for us to listen to.

On that note, an opinion and observation I might levy upon the symposium was that the speakers seemed pleased with the diversity of the concluding panel, but overall, I noticed that East Asian speakers dominated the symposium. In this symposium, the only South Asian representative was Kulkarni and the main Southeast Asian speaker was Linda Trinh Vo during the “Present” panel. Filipinos are also a notable Asian majority in California—a statistic that was mentioned during the “Present” panel—but the symposium did not include any Filipino speakers. I offer this as food for thought for any future symposiums, which I sincerely hope the Huntington will consider organizing.

I’ve vacillated tremendously between feeling “American” and not. Most of my life, this identity has been dictated by those around me, not myself. My parents are immigrants from two different countries, bringing their own traditions here, choosing what to keep and remixing “American” traditions. We often didn’t know what the norm for everyone else was; I would speak with classmates about how I celebrated holidays to mild surprise or quizzical looks. Up until the age of maybe 18, if you had asked me, I probably wouldn’t have identified as American. When I left the U.S. to study in Scotland, I felt the label of “American” be applied to me by others, due to the accent and prevalence of Americans attending university at St Andrews. It’s only as I’ve returned that I’ve felt that I could define and choose what being “American” really means to me.

And I think I’ve come to a similar conclusion as many others in my generation: that no one can truly define whether another person is “American” or not, since, excepting Indigenous folks, all of us are immigrants to this country in one generation or another. What is “American,” except the multifaceted evolution of many cultures meeting?

However, while representation does matter, the type of representation, as well as the action to accompany it, matters more. While the definition of American depends on each individual, it seems that there is agreement regarding the responsibility that comes with that identity. Kulkarni quoted iconic Chinese American author and activist Grace Lee Boggs: “I’ve come to believe that you cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.” And my mother echoed the same thought in her own reflections on this symposium:

“But being American comes with responsibility. We have to give back to the country we now call home by engaging with our community and actively seeking out how we can contribute to society. In areas where we have influence, we have to advocate for all people of color and use our voices to speak for those who can’t. At the very least, sharing our stories might help others understand that while we don’t look like them, we have similar hopes and dreams, and are striving for the same happy outcomes.”

And I wholeheartedly agree with those sentiments. We, as a collective humanity, have shaped the world as we know it today. Thus, my personal answer to Chang’s question of how to build a community that endures is simple: by living and acting upon the change we envision. For me, that’s listening and making space for others to tell their stories, sharing my own, and working to create communities of respect, care, inclusion, and hope wherever I am.

I highly encourage anyone interested to watch the videos of each set of panels—many thanks to the team at the Huntington for assembling this symposium.