By Eliza Siegel

The financial futures of millions of student debt-burdened Americans remain uncertain as President Joe Biden’s hotly contested student loan forgiveness plan awaits the verdict of the Supreme Court after the court heard arguments from both the White House and several challengers to the plan on Feb. 28.

While the promise of having thousands of dollars of debt eliminated would be substantial for many people carrying student loans, the court’s final ruling holds particular significance for one group of former students: Pell Grant recipients.

Should the White House prevail, those who received a Pell Grant while attending college could be eligible for up to $20,000 of loan forgiveness, double the maximum amount for non-Pell Grant students. While it might seem illogical for grantees to be eligible for more loan forgiveness than nongrantees, Pell Grant recipients typically face more challenges to loan repayment. They also comprise more than 60% of the borrower population, making the greater level of potential loan forgiveness more impactful.

Pell Grants have been awarded to students with the largest demonstrated financial need since 1972 under the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. The grants, which do not need to be repaid, have historically offered an important non-loan-based form of financial aid for low-income students, boosting enrollment rates and improving outcomes for poorer students.

Ahead of the 2023-24 school year, the government announced an increase in the Pell Grant maximum to $7,395—$500 more than was allotted the previous year and the biggest bump in a decade.

However, much has changed over the five decades since the program was rolled out. The price of tuition and other fees, as well as the rate of inflation, have increased significantly, outpacing incremental yearly increases to Pell Grant maximums. In 2017, the grant covered an average of 29% of college expenses at public four-year schools, a striking decline from the 79% it covered in 1975.

Rising tuition costs and the mounting student loan debt crisis have also chipped away at college enrollment rates over the past decade, a trend greatly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Between the fall terms of 2019 and 2022, there was a 7% drop in students registering for school.

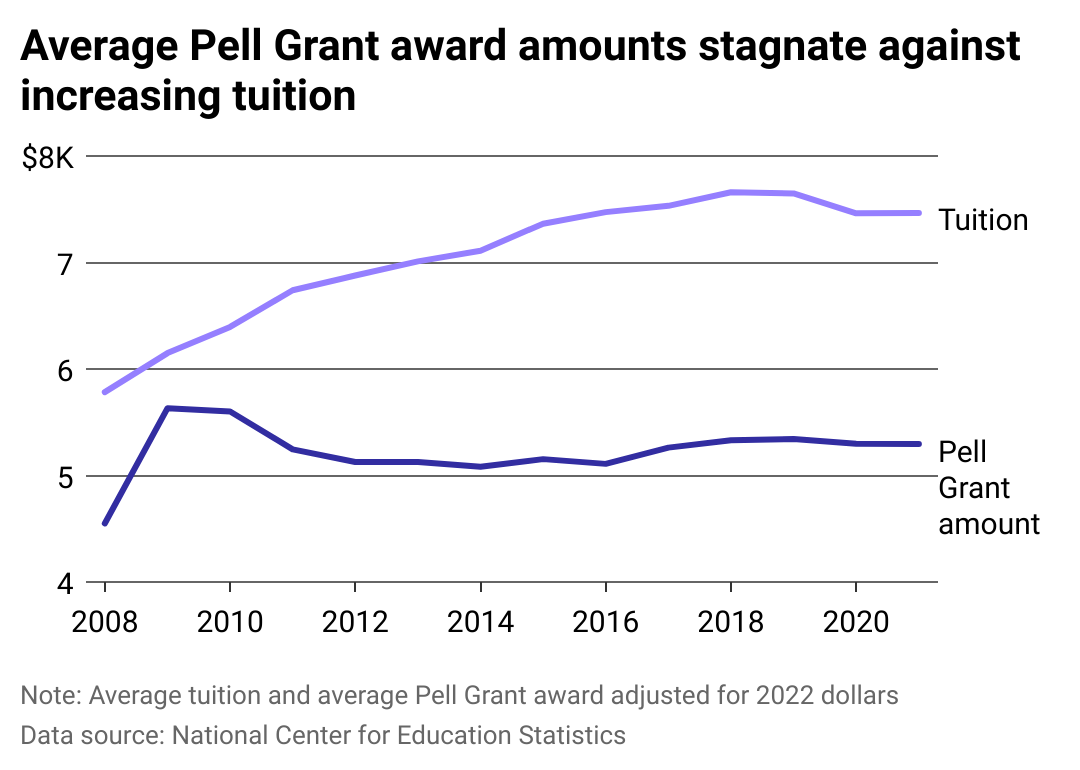

Best Universities analyzed trend data up to the 2020-21 academic year from the National Center for Education Statistics to see how Pell Grants and other financial aid types stack up over years of rising tuition. The analysis includes data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, which colleges and universities report.

Best Universities

Average tuition has steadily increased since 2002—but Pell Grant amounts have remained relatively consistent

According to NCES data, which gathered information from more than 1,500 institutions, in the 2021 academic year, the average amount of tuition and required fees for full-time undergraduate students at public postsecondary institutions operating on an academic year calendar system was $6,527—up sharply from $4,961 just a decade before.

Despite the maximum Pell Grant awards increasing every year since 2012, the average amount of money actually awarded to low-income students through Pell Grants has remained more or less the same year over year.

This incongruity persists even as tuition costs have continued to climb dramatically over the last decade. As the stagnation of average Pell Grant awards creates an even wider gap between non-loan-based aid and the average cost of attending college, total U.S. student loan debt has simply continued to rise and is now a staggering 774.1% more than it was in 1995.

Best Universities

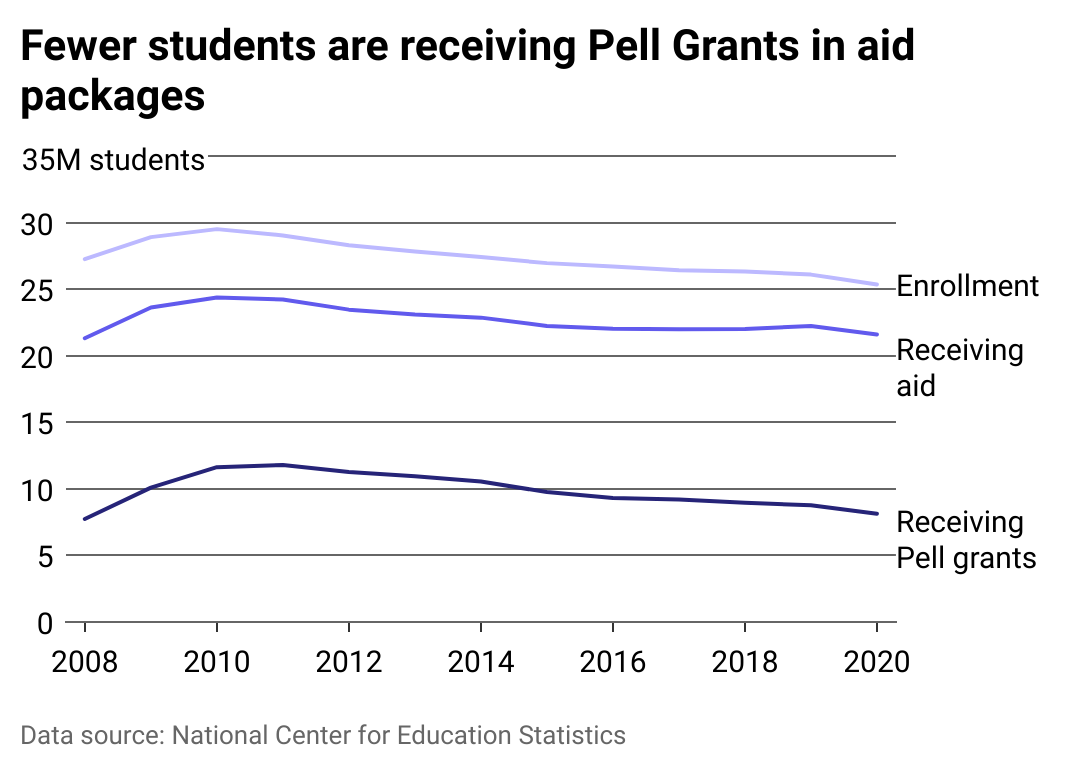

Share of students receiving financial aid—including Pell Grants—is declining

The number of students receiving financial aid has generally declined since 2010, but the share of financial aid awardees took an especially dramatic hit at the onset of the pandemic.

Far fewer students applied for financial aid after the pandemic began, according to reports from the National College Attainment Network and Sallie Mae. The number of Free Application for Federal Student Aid applications filed hit a 14-year low in 2021. FAFSA applications are the main avenue for receiving both loan and grant-based financial aid.

The decline in FAFSA applications suggests fewer low-income students applied to college after the pandemic began, and higher-income students made up an even larger share of college-goers than they did previously. The drop in the number of Pell Grant recipients also correlates with the downturn in FAFSA applications since Pell Grants are only awarded by applying through the FAFSA.

This story originally appeared on Best Universities and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.