By Tim Haddock

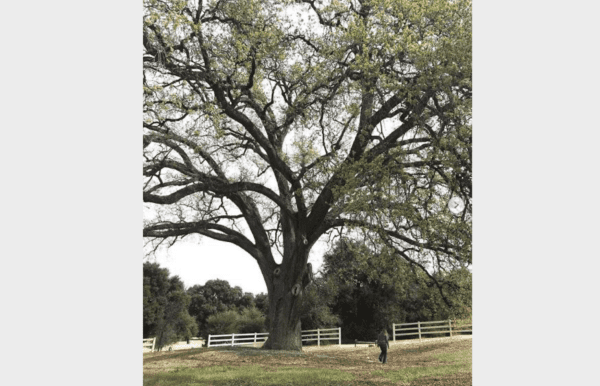

It was 20 years ago when a small group of environmentalists rallied to save an oak tree from developers and urban expansion in Santa Clarita.

Their small-scale movement rapidly grew into an international effort in support of the tree called Old Glory. And now, the activists who saved it two decades ago are returning to celebrate the tree’s survival and its message of unity and preservation.

A group led by the Santa Clarita Organization for Planning and the Environment will host a celebration of Old Glory at 1 p.m. Saturday at Pico Canyon Park, where the tree was moved and continues to grow.

Twenty years ago, the tree was in the middle of a road that was planned for the Newhall Ranch development and community. When it came time for the developers to build the road, Lynne Plambeck, who was a member of the Newhall County Water District Board, and other environmentalists reviewed the plans for the road construction to double-check which trees were properly designated to remain or be removed.

They found that Old Glory was marked to be removed, even though it was in the original plan.

Barbara Wampole, Cynthia Harris and Plambeck started to protest the removal of the tree. On the day it was scheduled to be removed, John Quigley joined Plambeck, Wampole and Harris to protect the tree. Quigley moved into the tree and Plambeck started a movement on the ground to save Old Glory.

“He (Quigley) went very early in the morning on the day they were going to push the tree over with a big bulldozer and he was up in the tree,” Plambeck said. “The sheriff’s (deputies) came and tried to have us leave.”

She told the deputies, “There is a person in this tree and you can’t push it over.”

The group stopped the tree from being removed that day, but the victory was only temporary. The developer continued efforts to remove the tree in spite of the activists determined to save it. A fence was erected around the tree, trapping the foursome inside.

“They falsely imprisoned us,” Plambeck said. “They just didn’t know what they were getting into messing with the ladies and the tree sitter. I don’t know who was tougher.”

The small group of protesters grew slowly. It attracted children from the community, national and international media. And Old Glory, named by two boys from Santa Clarita, became a celebrity in a few weeks.

Friends of the Santa Clara River and The Oaks Conservancy joined the campaign. Plambeck helped form a task force to work with the developer and political authorities to come up with options for Old Glory.

“It became quite a movement. The tree had a mailbox labeled Oak Tree No. 419 and the post office was delivering mail to it for a while,” Plambeck said. “He would get lots of mail.”

Shawnee Badger was 9 years old when she and her mom Deborah visited Old Glory. She was a fourth-grader at Castaic Elementary School and joined a group of youth activists to help save the tree. She remembers seeing other trees with markers on them — little flags and signs.

She said she thought those trees were going to be killed or removed too.

“I remember knocking them down, tearing them off,” Badger said. “These other trees were marked. It nurtured this little rebellious activist spirit.”

She was going to save all the trees. Twenty years later, Badger, one of the organizers of Saturday’s reunion, is still trying to save all the trees and the rest of the environment. The movement to save Old Glory sparked a lifetime of activism. She credits that time for turning her into the person she is Friday.

“I remember being so deeply affected and so deeply impacted by what I saw, by the demonstration, by the dedication, and by putting actions to beliefs,” Badger said.

“I didn’t grow up being political or an activist. From there on out, it totally changed me and shaped my development. I constantly have thought back to that moment as the moment that really shaped me. I learned them through people like John Quigley.”

Quigley says he feels a special connection to nature. He grew up near the woods and walked through them to school when he was a child. He used to climb the trees on his way to and from school.

It’s where his love of trees and the environment began and he wants to share that connection with others.

“A lot of society is so blind to nature now because of all of this technology,” Quigley said. “We are a part of nature and we come from nature. That moment with Old Glory was just a moment where it feels like there was a higher power at work (that) brought all the right people together to save that tree.”

For Badger, Quigley was a real-life Lorax. She equated the man living in the tree with the tree-loving character from the Dr. Seuss book. It showed her how a group of kids and environmental activists could influence community and political decisions. She also said because there were so many people paying attention to Old Glory and caring about what happened to the tree, it helped it survive and thrive.

“When we give something our full attention, the outcome is going to be better,” she said.

Quigley said he embraces the comparison to the Lorax and that he is grateful he was able to play such a crucial role in saving Old Glory.

“I think the Lorax is an amazing character who saw what was happening in that story to nature, and who was a prophetic voice that we don’t rush to industrialize,” he said.

Plambeck estimates Old Glory is over 400 years old. It was in the Santa Clarita Valley long before the developers and the environmentalists entered the arena. During the campaign to save the tree, indigenous people and the Latino community joined. It drew the attention of media from Europe and India, and inspired other protests to save trees throughout the country.

“Everybody felt connected to this tree,” Plambeck said. “It was very wonderful.”

Quigley stayed in the tree for 71 days, through cold winter months in December and January in 2002 and 2003. The activists and the developer finally agreed instead of knocking the tree down to move it about a quarter-mile into the park to clear the way for the new road.

Plambeck said initially she wasn’t happy with the decision. It wasn’t the original agreement the developer made for the area and surrounding wildlife. Plambeck said it was supposed to be preserved as a green zone and she wanted the developer to build the road around the tree.

“However, as it turned out, it seemed to work,” Plambeck said. “A lot of times trees do not do well when they move. It does seem to be surviving.”

To celebrate its survival, members of the community plan to have an afternoon of rallies and speeches Saturday, a reunion of sorts to remember how the drive to save Old Glory succeeded. Plambeck said the day is to promote awareness, but she also wants it to illustrate how teamwork can be used to accomplish difficult goals.

“It’s awareness. It’s understanding how important oak trees are. People are starting to understand how important oak trees are,” Plambeck said. “People came together from different cultures, different political viewpoints, and they saved a tree together.

“Our community has become so polarized that maybe this can be a symbol of what happens when people work together.”