Riverside County prosecutors are scrambling to refile cases — including child sexual assault cases — booted by Superior Court judges, who are justifying the dismissals by citing lack of available courtroom space, the District Attorney’s Office said Tuesday.

According to the agency, between Jan. 25 and Jan. 30, three felony sex cases were vacated by Judges Helios Hernandez and Jeffrey Prevost at the Riverside Hall of Justice. During that period, several judges were on training assignments, while others were on sick leave, and their courtrooms were closed.

The lack of court space for trials prompted Hernandez and Prevost to dismiss the matters, prosecutors said.

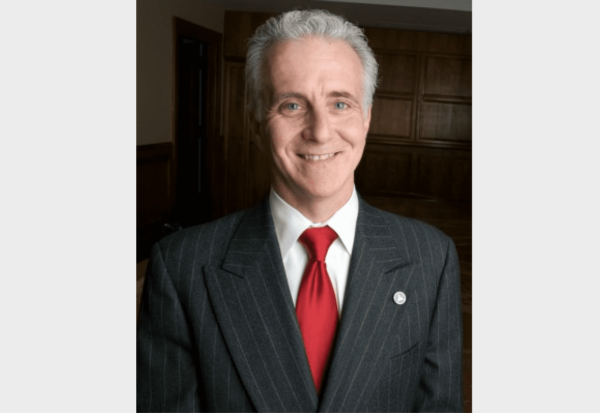

“I understand the need for ongoing training. However, when our courts are experiencing a crisis and engaging in the mass dismissal of cases, victims of crime deserve the right to be the priority,” District Attorney Mike Hestrin said. “Over the last three months, the courts have dismissed over 1,500 cases, some of which are serious felonies, such as these three sexual assault cases involving children.”

The dismissed cases were People v. Daniel Cintron, People v. Norman Martinez Garcia and People v. Angel Torres Salas.

In each instance, when the prosecution announced that it was ready for trial, instead of placing the cases on hold and continuing them a few days until courtrooms came available, the two judges vacated them, according to the DA’s office.

“In the Garcia case, our office has filed six felony counts pertaining to two underage victims — including charges of rape and oral copulation involving one of the young victims,” according to a DA’s statement. “Because there are two different victims in this case, the defendant faces a possible life sentence if convicted as charged.”

Prosecutors immediately refiled each case with fresh criminal complaints, the agency said.

“The courts being aware of this shortage of courtrooms should be able to anticipate the needs of public safety and reschedule their training until the courts are fully operational,” Hestrin said.

Last week, the county Board of Supervisors ordered the Executive Office to review the bases for the mass dismissals and return to the board with a report by mid-March listing real world solutions.

“Our system of government does not work without a functioning court system,” Supervisor Karen Spiegel said. “This board needs to engage on the issues and find solutions. We’ve been talking about it. Now we have to do something about it.”

The Association of Riverside County Chiefs of Police and Sheriff — ARCCOPS — has called for an immediate end to the dismissals.

The lion’s share of cases — 67% — have been vacated by judges at the Larson Justice Center in Indio, with another 15% dismissed by judges at the Banning Justice Center, roughly 10% by judicial officers at the Southwest Justice Center in Murrieta, 7% by the bench at the Riverside Hall of Justice, and a negligible 1% by judges at the Blythe Courthouse.

Figures indicated 93% of vacated cases have been misdemeanor filings. DUIs accounted for the highest number of dismissals at 36%, followed by domestic violence complaints at 26%. Assault filings made up about 5%, and sex crimes were near the bottom at 2%, according to data.

The dismissal binge began on Oct. 10. Most of the cases were added to dockets during the public health lockdowns, when courts suspended many operations under emergency orders from the California Office of the Chief Justice.

A backlog of roughly 2,800 cases developed. The chief justice’s orders expired on Oct. 7.

Superior Court Presiding Judge John Monterosso released a statement on Oct. 25 acknowledging the court system was bearing a heavy load, traced to the lockdowns and consequent changes in court operations.

“The genesis of the current set of circumstances is the chronic and generational lack of judges allocated to serve Riverside County,” Monterosso said.

He emphasized the county has 90 authorized and funded judicial positions, but a 2020 Judicial Needs Assessment Study noted that 115 judicial officers are needed to ensure efficient operations throughout the local court system and prevent logjams.

“While the law allows a court to continue a case beyond the statutory deadline for ‘good cause,’ the decision on whether ‘good cause’ exists is an individualized decision made by the trial judge based on the law and the facts of the case,” Monterosso said.

Hestrin questioned the legitimacy of basing dismissals on a deficit of judicial resources, given that “this has been the case as far back as anyone can remember.”

The backlog is reminiscent of the cumulative impact of a buildup of unresolved criminal cases in 2007 that prompted the state to dispatch a “judicial strike team” to Riverside County to help sort through criminal cases clogging the court system.

At the time, the Superior Court virtually halted civil jury trials for months while judges focused on reducing the strain. An empty elementary school was even converted into a makeshift courthouse.