By Eliza Siegel, Stacker

Over the course of only a few generations, Americans’ relationship with things—and the packaging that comes with those things—has radically changed. Shifts regarding where goods are purchased, how they’re produced, and what they’re made of have altered the economy and the environment.

The EPA defines packaging waste as materials used to wrap, ship, and protect wares, including food, cosmetics, or medicine, thrown out within a year of being purchased. That adds up to a lot of material, and some lawmakers and companies have tried to combat the volume. Eight states and several cities across the U.S. have banned single-use plastic shopping bags, for example. Many companies now use post-consumer recycled materials for their packaging and the reusable water bottle industry, valued at $8.6 billion in 2021, is projected to grow to $12.6 billion by 2030.

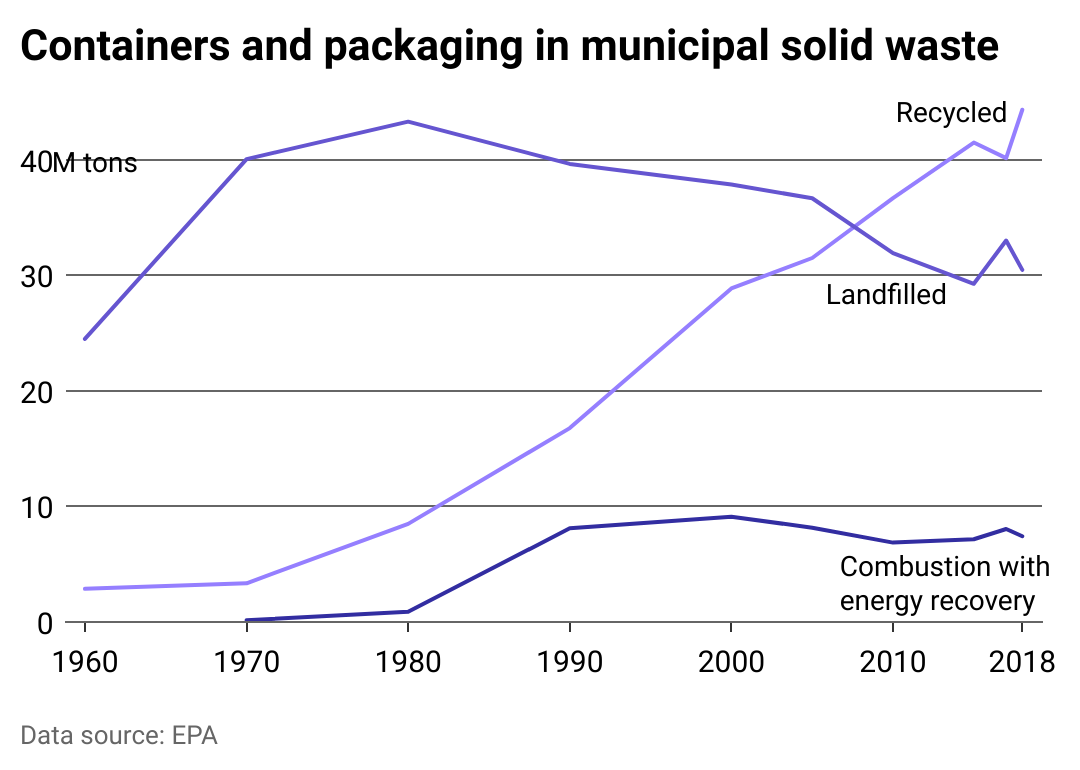

However, despite these interventions, disposable packaging shows no signs of slowing down—the bottled water industry is estimated to be worth $510 billion by 2030. Packaging accounts for almost one-third of all municipal solid waste in the U.S., according to the EPA. In 2018, that came out to about 82.2 million tons. Although recycling of packaging waste in the U.S. has steadily increased since 1970, more waste is being generated and landfilled than ever before.

Turbulence in the recycling industry has also made the process of reclaiming material more difficult and expensive. Before 2018, China recycled nearly half of the world’s waste, including a large proportion of U.S. recyclables. When China passed a law that banned the import of many plastics and other recyclables, the U.S. redirected its flow of waste to other countries, leading to environmental issues and overwhelmed systems across Asia and Africa. The resulting recycling crisis has meant that more and more American recyclables have ended up in landfills, and recycling has become more expensive, limiting infrastructure in certain parts of the country.

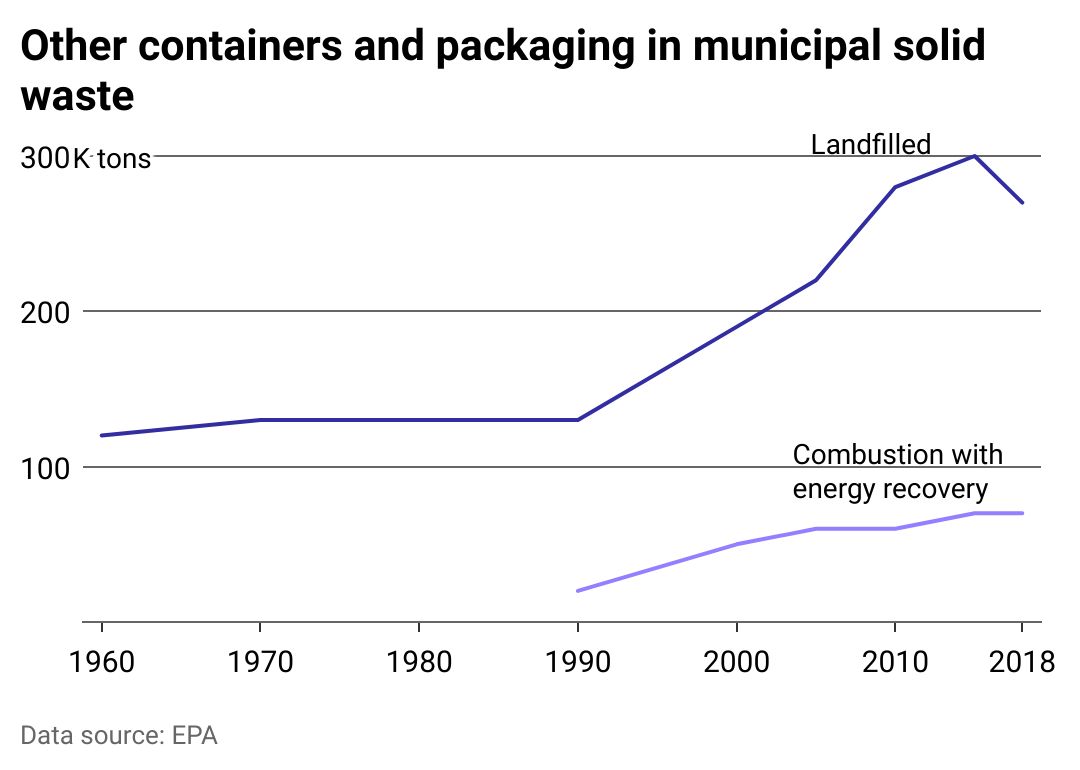

Another standard waste disposal method, combustion with energy recovery—or waste-to-energy—involves the controlled burning of waste, which lessens the amount of waste directed to landfills while also creating usable electricity. Early waste-to-energy plants were relatively unregulated and produced harmful emissions, but new standards in the 1990s significantly reduced these air pollutants. Combustion with energy recovery still accounts for a relatively small amount of packaging waste disposal in the U.S., primarily due to the relative ease and affordability of landfilling.

To gain more insight into what happens to different types of packaging after being thrown away, The Rounds examined historical data from the Environmental Protection Agency to see how material disposal has changed over time. The packaging materials examined used one of the three main methods of waste disposal: landfilling, recycling, or combustion with energy recovery.

The Rounds

What happens to containers and packaging after use

Since the 1970s, packaging recycling in the U.S. has steadily increased almost yearly. Landfilled packaging waste, on the other hand, peaked in 1980 and slowly but fairly consistently declined over the following decades.

Around 2007, the amount of recycled packaging waste surpassed the amount put into landfills for the first time. Disposing of packaging waste through combustion with energy recovery increased in popularity in the 1980s but started to plateau in 1990. The expansion of the Clean Air Act that same year increased government oversight and regulation of toxic air pollutants and ozone-deteriorating emissions. These measures required waste-to-energy plants to introduce air pollution filters.

Despite upward trends in recycling and a decline in landfilling of packaging waste, the U.S.’s overall amount of packaging waste generated has increased by millions of tons nearly every year, growing from 27.37 million tons in 1960 to 82.22 million in 2018.

And in 2015, recycling rates for packaging waste faltered for the first time since the process began, mainly because a combination of plummeting oil prices and an economic downturn in China decreased the value of American recyclables internationally. This downturn led to the closure of many domestic recycling plants and increased packaging waste going to landfills.

The Rounds

Aluminum containers

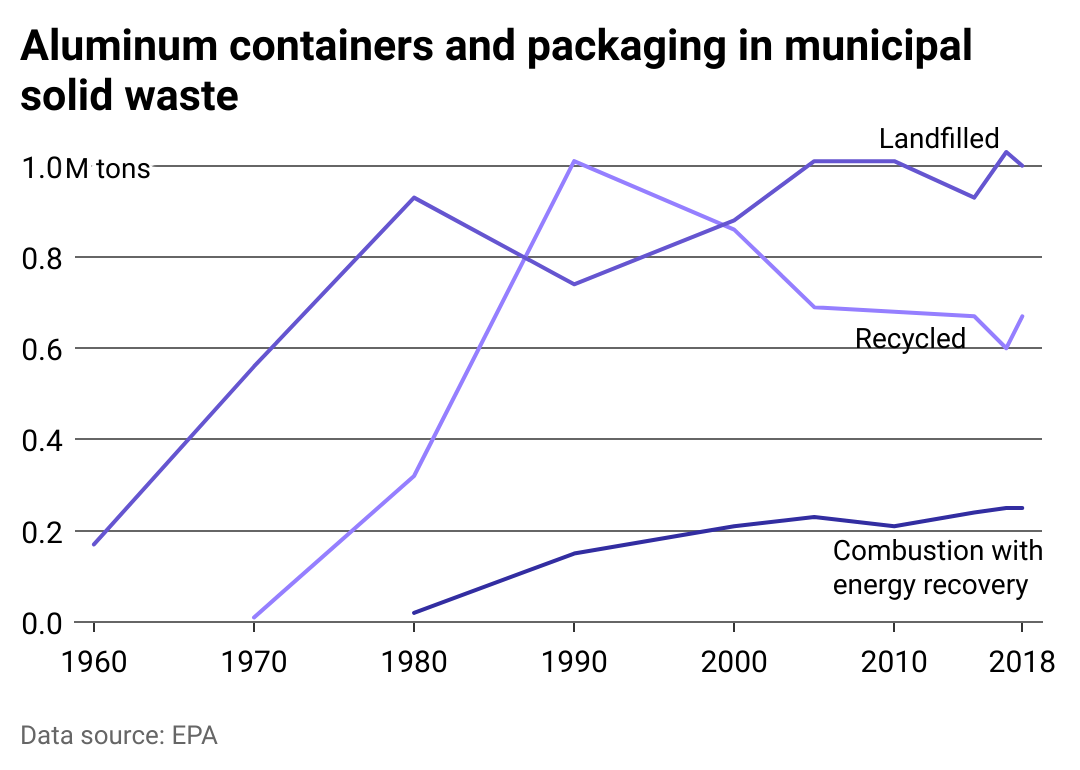

Aluminum cans and foil make up the bulk of aluminum packaging in the U.S. Because the metal can be recycled “infinitely” while maintaining its original properties, many manufacturers have recently opted for switching plastic packaging for aluminum, citing it as a more sustainable option.

While aluminum has a higher recycling rate than plastic, most beverage cans in the U.S. go to landfills, mainly due to poor sorting, lack of recycling infrastructure, and because landfilling remains cheaper than recycling in many parts of the country.

The lack of a national deposit system for bottles and cans also accounts for aluminum’s relatively low recycling rates. Currently, only 10 states and Guam have programs that give consumers a financial incentive to recycle beverage containers. However, recycling rates in those states are significantly higher than those without deposit programs.

The Rounds

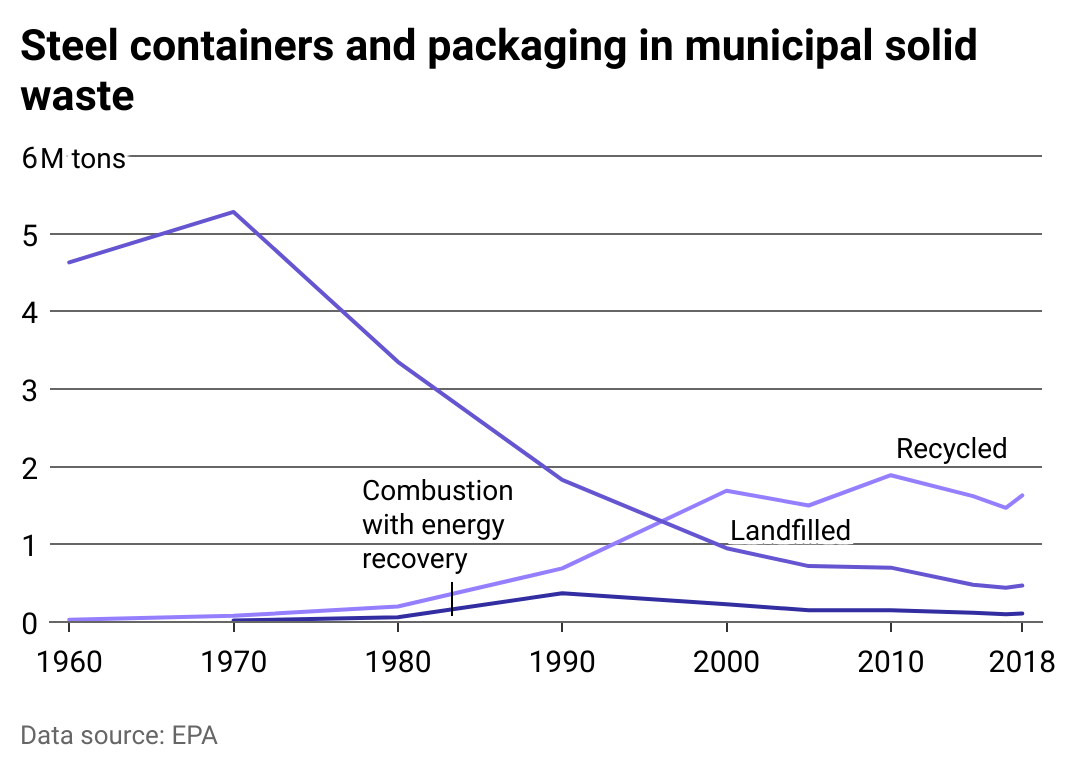

Steel containers

The amount of steel packaging waste generated in the U.S. began decreasing dramatically in the 1970s and ’80s, largely due to plastic’s increasing popularity and innovations in lighter-weight, thinner steel packaging. Steel food cans are roughly 46% lighter today than 30 years ago, and people began to recycle them at a higher rate than landfilling in the late ’90s.

Steel packaging recycling hit an all-time high in Europe in 2022, averaging 85.5%.

The Rounds

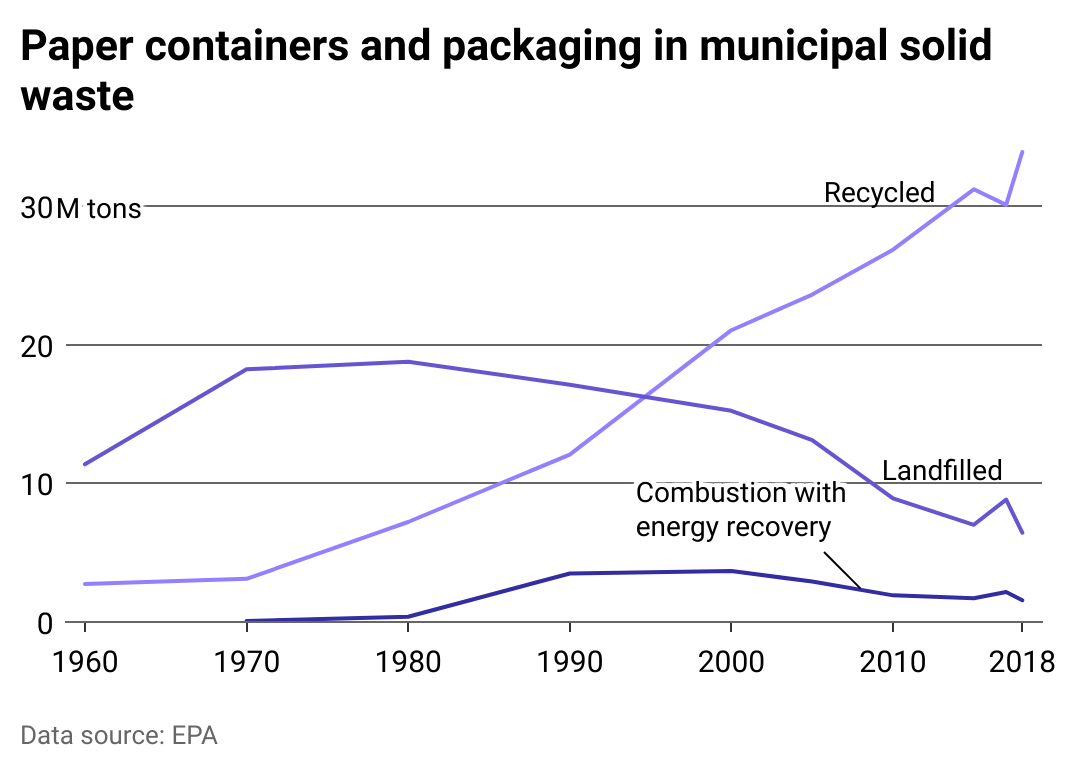

Paper and cardboard containers

Paper and cardboard packaging waste had an overall recycling rate of 80.9% in 2018, one of the highest of any material. Corrugated cardboard boxes, which make up the majority of shipping boxes and comprise the largest category of packaging waste in the U.S., had a recycling rate of 96.5% that same year. Other paper and cardboard packaging sources are beverage cartons, wrapping paper, and cosmetics containers.

Demand for cardboard and paper packaging skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic when supply chain issues and in-person services made ordering goods online more popular than ever. Corporations like Amazon began hoarding cardboard in anticipation of the increased demand, contributing to a shortage of the material and driving up cardboard prices in 2021.

In just one year, the price of a ton of cardboard went from $25 to $75, according to Resource Recycling. The cardboard shortage also meant a switchover to plastics use, especially for smaller businesses that could not compete with Amazon and other large corporations’ bids for cardboard packaging.

The Rounds

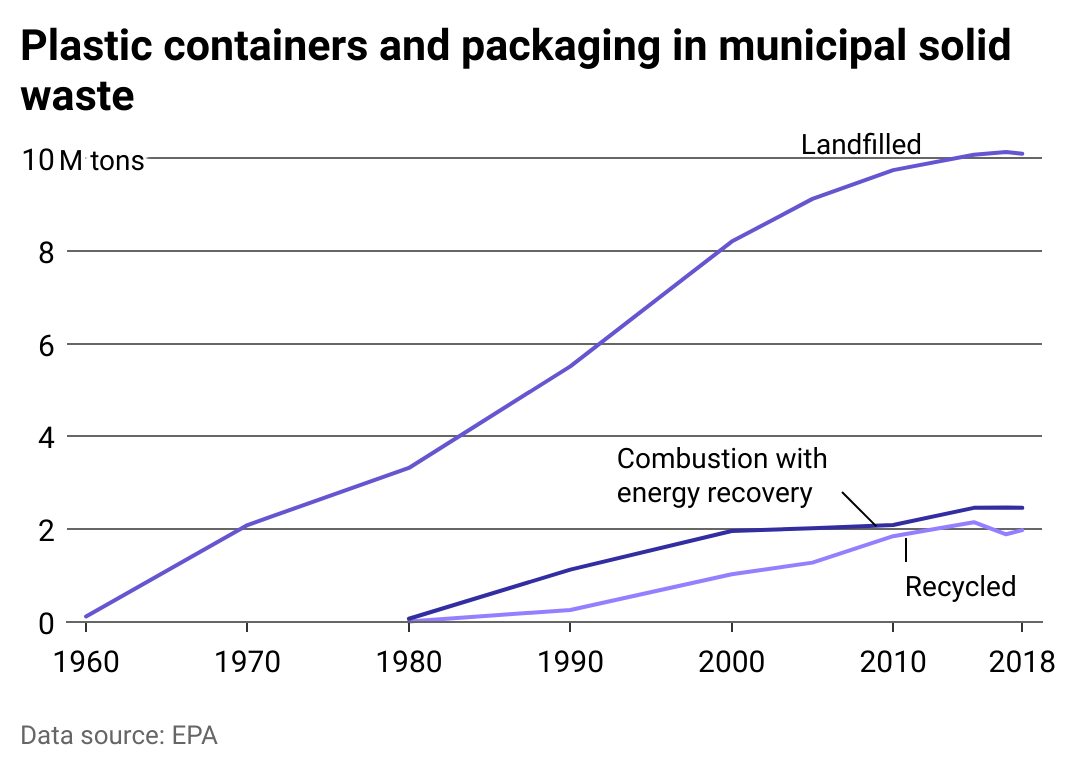

Plastic containers

Plastics make up a large portion of packaging waste, but have the lowest recycling rate out of any packaging material at 13.6%. Plastic packaging waste includes water bottles, other beverage bottles, jugs, shopping bags, cling films and wrappers, and many other items.

The generation of plastic packaging waste saw an extreme increase between the 1960s, when plastics were first introduced into the consumer goods market, and the 2010s, when they became a dominant type of packaging.

While many types of plastic packaging are not recyclable, most of the kinds that are recyclable still end up in landfills. However, the false belief that plastics are recycled most of the time shapes consumer habits around single-use plastics and obscures the degree to which plastics end up in the trash.

According to Consumer Reports, the cultural belief that most plastics are recycled has been shaped over time by campaigns launched by the world’s largest plastic producers and corporations: petroleum and gas companies, and beverage industry giants like Coca-Cola.

Investigations into these corporations have revealed they knowingly created false messaging to sell Americans the idea that all plastics would be recycled as a marketing strategy to sell more virgin plastic. The recycling crisis in 2018 only worsened the odds of plastic packaging waste getting recycled, with between 20% and 70% of all plastic waste sent abroad for recycling ending up in a landfill.

The Rounds

Glass containers

Until the second half of the 20th century, the reuse of glass bottles and containers was built into consumer habits (think milkmen and the delivery and collection of glass bottles of milk). Mason jars and the ability to mass-produce glass containers made them particularly cheap and convenient for reuse. After World War II, when items like paper cups were introduced for convenience, a new American trend emerged: the use of disposable, single-use products and packaging.

An increasingly disposable culture of consumption decreased the need for reusing glass, resulting in more glass packaging ending up in landfills in the ’60s and ’70s. The generation of glass packaging peaked in 1980 and has decreased since, largely replaced by plastic packaging, which is cheaper to manufacture and less heavy—and therefore less expensive—to transport.

The Rounds

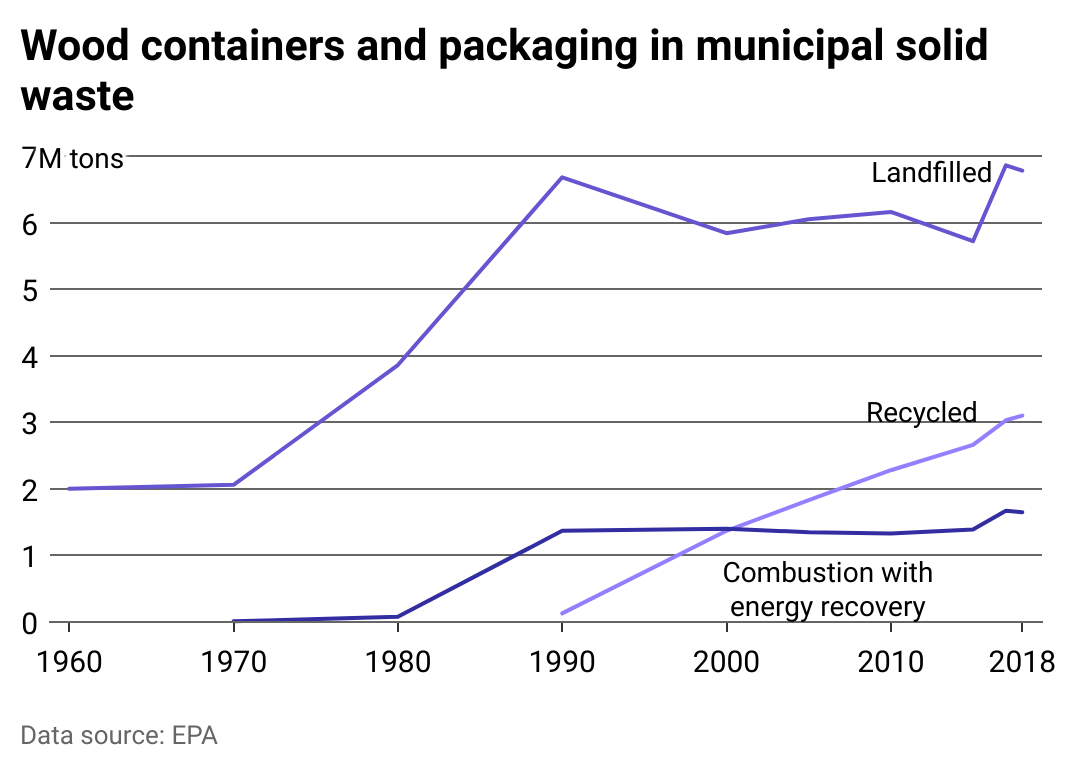

Wood containers

Wood pallets and crates make up most wood packaging, and most of it ends up in landfills after use. Recycling wood packaging consists of chipping for mulch or creating particle boards, which can turn into other items.

Wood pallets, used to transport most goods through the supply chain, have environmental impacts from their production to their disposal. The sheer volume of wood harvested to create pallets has raised concerns about deforestation. Meanwhile, numerous invasive insect species are known to jump continents in wood pallets and crates, wreaking ecological havoc on their new environments.

This story originally appeared on The Rounds and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.