The Postal Service can legally deliver abortion medications in the U.S. — including to states with abortion restrictions or bans — according to a Justice Department decision posted online late Jan. 3. The Postal Service requested that the Justice Department provide guidance on this issue a week after the Supreme Court’s conservative majority voted to overturn the landmark Roe v. Wade decision in June 2022. That ruling, which sparked intense debate across the U.S., led to abortion restrictions and bans in many states.

In its decision, the Justice Department ruled that sending, delivering, and receiving abortion drugs by mail is not in violation of the 1873 Comstock Act — which aimed to prevent morally “corrupt” items from being delivered by mail — because there is no way to determine that the intent of the recipient is to commit an unlawful act. There are also no federal restrictions on the drugs in question.

Considering the fraught and deeply political ways in which abortion is discussed and legislated in the U.S. today, it’s easy to forget the issue was not always a partisan, or even a moral, one. Rather, attitudes toward abortion have changed over the centuries, often evolving alongside political and historical moments that reflect shifts in power and privilege.

In Colonial times, abortion was not a matter of federal or ethical significance, but a common decision made and acted upon by pregnant people and their midwives. Two centuries later, abortions were outlawed in every state. The matter of who gets to make decisions about abortion — whether it be the federal government, state legislators, or individuals — has historically been tied up in changing philosophies about bodily autonomy, the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, the advent of the medical industry, and, eventually, the merging of religion and politics to form the party system we know today.

Stacker consulted historical records, scholarly research, court documents, medical journals, news reports and data from the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and advocacy organization, to trace the history of attitudes and policies around abortion in the U.S. from colonial times to the present.

A note on the use of gendered language in this article: In recent years, the language used to talk about gender has shifted to meet the understanding that gender is a spectrum. Likewise, matters historically categorized as “women’s issues,” such as pregnancy and abortion, don’t only impact cisgender women, but also trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people.

In an effort to stay true to the language used in historical accounts cited in this article, we have employed language as it was used during those times. However, for the parts of this article that refer to present-day issues, we have used more expansive terminology.

Pre-1850: Abortions in early America are commonplace

British common law followed the colonists to North America and formed the basis of the original laws and customs in the American Colonies. Abortion, like birth, pregnancy, and other processes involving women’s bodies, was largely handled by communities of women.

Knowledgeable midwives were responsible for guiding women through birth and did so with the participation of the woman’s female family and friends — a process now known as “social childbirth.” Similarly, abortions were most often seen as a decision to be made by a pregnant woman and her midwife; they were most often induced using herbs known for “restoring the menses,” historian Leslie Reagan wrote in her 1997 book “When Abortion Was a Crime.”

Abortions in early America were ubiquitous — some historians estimate between 20% and 35% of pregnancies in the 19th century were aborted. They were also uncontroversial from a moral and legal perspective, at least up until the quickening — when a pregnant woman could first feel the fetus move or kick in the womb—usually around the 20th week of pregnancy.

Although there was no real legislation regarding abortion until the early 1800s, this pre- and post-quickening distinction would set a precedent for a series of laws passed in the 1820s and 1830s, starting with an 1821 Connecticut abortion law that officially criminalized medicinal abortion after quickening. The law penalized only the provider of the abortion medication and was largely seen as a means of protecting women from other often-lethal abortion medicines

Mid-1800s: Birth of the American Medical Association shifts abortion oversight from midwives to doctors; abortion is criminalized

It wasn’t until halfway through the 19th century that matters of pregnancy, birth, and abortion shifted away from a social- and community-oriented model steered by midwives toward a male-dominated medical model controlled by doctors.

The single most influential factor in this societal shift was the founding of the American Medical Association in 1847. Prior to the AMA’s founding, more medical schools opened and white male physicians sought to distinguish themselves from the types of providers people typically relied on — namely midwives, herbalists, and local healers.

In 1857, the AMA established a Committee on Criminal Abortion, which launched a campaign to discredit midwives’ work and elevate the AMA’s practices to an “elite” status. To achieve this end, the AMA argued for making abortion a matter to be decided and performed by physicians, not women and midwives. It also adopted a moral argument that sought to cast doubt upon women’s knowledge of their own bodies and pregnancies, circulating a report that lampooned “a belief, even among mothers themselves, that the foetus is not alive till after the period of quickening.”

The campaign to place abortion and birth in the hands of white male doctors was bolstered by language that stoked racial fears about declining birth rates among white populations, an influx of immigrants to the U.S., and the recent emancipation of formerly enslaved Black people, according to historian Leslie Reagan. Horatio Storer, who orchestrated the AMA’s campaign to criminalize abortion, wrote that the settling of the American West and “the destiny of the nation” rested on “the loins” of wealthy white women—a mission being jeopardized by these women having too many abortions.

These developments coincided with the Catholic Church’s stance reversal on abortion. Even though the church abided by Pope Gregory XIV’s 1591 assertion that abortion was only homicide after “ensoulment” — which was believed to happen at quickening — for nearly 300 years, Pope Pius IX declared all abortion forbidden in 1869. This stance remains in effect today.

By 1880, every state had passed legislation that made abortion a crime, except in cases where the mother’s life was at risk. This kicked off the “century of criminalization” — from 1880 to when Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 — forcing abortions underground.

1960s: ‘Back-alley butchers,’ birth control, and protests

The 1960s ushered in a new era of social and political change — the civil rights, women’s liberation, and anti-Vietnam War movements converged to create a sense of optimism and energy, particularly among younger generations. The sexual revolution in particular began to shift conservative norms around what kinds of sexuality were acceptable, and questions about women’s sexual empowerment entered mainstream conversation.

However, with abortion still outlawed in every state, people seeking to terminate their pregnancies were frequently forced to do so in unsafe conditions. People who resorted to self-inducing abortions using a notoriously grisly array of techniques — the infamous coat hanger among them — were often poor and could not afford the steep fee of employing an “abortionist” to perform the procedure. Even those who were able to pay someone to perform the procedure were often injured in the process. In fact, the phenomenon was so common that most big-city hospitals had septic abortion wards — sometimes referred to as “septic tanks” — specifically meant for people ailing from botched abortions.

While the exact number of illegal abortions in the years leading up to Roe is unknown due to underreporting, estimates from the Guttmacher Institute place the number anywhere between 200,000 and 1.2 million per year in the 1950s and ’60s. The plenitude of people seeking abortions can be attributed in large part to the fact that contraceptives were not accessible until 1965, when Griswold v. Connecticut made the use of birth control pills legal for married couples — unmarried people would have to wait another seven years.

During this time period, some reproductive rights activists also developed ways to help people access safe and affordable abortion care. The Jane Collective of Chicago famously formed in the ’60s and set up a call line, which connected those seeking abortions with the group’s own provider. After a while, the women realized they could learn to perform the procedure themselves, allowing them to expand their services to more people at a much lower cost.

By the late ’60s, the work of activists, changing attitudes around sex, and the impact of Griswold v. Connecticut were beginning to have an impact on how lawmakers and the general public viewed abortion. Over the course of that decade, abortion had gone from a taboo subject people whispered about, to something shouted about in protests.

1970s: Roe v. Wade protects women’s right to abortion; politics shift

Perhaps the most pivotal day for abortion rights came on Jan. 22, 1973 — the day the Supreme Court handed down its 7-2 decision on Roe v. Wade, rendering restrictive abortion laws across the country unconstitutional.

Despite the overarching implications of the ruling, public reaction was reportedly muted. This was, in part, due to the fact that abortion had not yet become a partisan or deeply politicized issue. In fact, many of the justices who voted in favor of Roe were conservatives and Richard Nixon appointees, including Justice Harry Blackmun, who delivered the majority opinion. In the immediate aftermath of the decision, the majority of the criticism of Roe came from the Catholic Church.

Abortion access improved quickly after Roe v. Wade. The septic abortion wards that had sprouted up in hospitals to treat complications from unsafe abortions were closed and replaced by clinics. Complication rates went down, and because of improved access to abortions early in pregnancy, the rate of abortions after the first trimester dropped from around 25% in 1970 to 10% in the first 10 years post-Roe.

And improved health outcomes weren’t the only big changes: In the years following the decision, political and social allegiances around many issues, among them abortion, shifted. For example, prior to Roe, evangelical Christians did not oppose abortion — many Southern Baptists even supported its legalization. Abortion was not a major political issue for the right at that time, and most Catholics, the most outspoken anti-abortion voter bloc, tended to vote Democratic.

But the ongoing civil rights movement, desegregation of schools, and prohibition of schoolwide prayer in public schools — among other factors — drove the Republican party further right. As the party increasingly became the socially conservative “party of family values,” the issue of abortion became a convenient — and more socially acceptable — proxy through which the right could channel its discontent around those issues as well as a growing sexual liberalness. Adopting an anti-abortion stance also helped the Republican Party convince more socially conservative Catholics to break with the Democrats.

By the end of the 1970s, these issues had converged to aid the rise of the Moral Majority, a right-wing movement led by televangelist Jerry Falwell that merged fundamentalist social and political conservatism and mobilized the Christian right, aiding in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and ushering in a new era of American politics.

1980s-2000s: Legal challenges to Roe v. Wade introduce restrictions

Starting in the 1980s, cases like Harris v. McRae and Webster v. Reproductive Health Services were already introducing restrictions to the abortion rights Roe initially promised. For example, Harris v. McRae restricted Medicaid funding for abortions to cases of rape, incest, and life endangerment, while Webster v. Reproductive Health Services upheld Missouri’s limitations on who could perform abortions, as well as where.

The 1992 ruling for Planned Parenthood v. Casey both reaffirmed Roe while also introducing a loophole through which states could restrict access to abortions: As long as state laws did not pose an “undue burden” on people seeking abortions before the point of fetal viability, those restrictions could be acceptable. This reworked the trimester framework established by Roe, which ensured access to abortion during the first two trimesters and allowed states to decide on restrictions or bans on third-trimester abortions.

In 2000, the Supreme Court heard Stenberg v. Carhart, which challenged a Nebraska ban on a late-term abortion method called dilation and extraction — controversially referred to as “partial-birth abortion.” The Court ruled the ban was unconstitutional because it posed an “undue burden” on those seeking an abortion, as defined in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. But only seven years later, this decision was contradicted by the Supreme Court’s Gonzales v. Carhart ruling, which upheld the passage of the Federal Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act. The act criminalized the dilation and extraction abortion method, the first time a specific technique was banned.

2020s: Roe v. Wade overturned; Postal Service allowed to mail abortion medication

Since Planned Parenthood v. Casey and Gonzales v. Carhart, states have passed increasingly restrictive laws around abortion, including banning other specific abortion methods and introducing mandatory waiting periods and counseling, gestational limits, parental consent for minors, and compulsory ultrasounds.

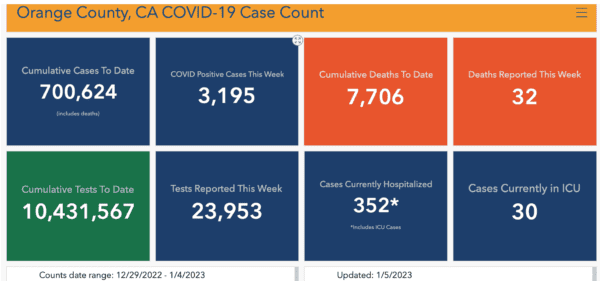

On May 2, 2022, a leaked Supreme Court initial draft majority opinion overturning Roe v. Wade inspired panic and protest amongst supporters of legal abortion and preliminary celebration for opponents of Roe; on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court released its ruling and Roe officially fell. In the aftermath of that decision, more than a dozen states banned most abortions and a number of others implemented prohibitive restrictions.

But while the legal fight over abortion rights is still underway in many courtrooms, 2023 has brought with it two key wins for supporters:

On Jan. 3, 2023, the FDA announced a new ruling allowing retail pharmacies to stock abortion pills. While a prescription will still be required to acquire the medication, the move represents a large expansion of access for the drugs — particularly for Mifepristone, which was previously available only from select providers and a few by-mail pharmacies. Now, all pharmacies can dispense the drugs, though they are not required to.

The same day as the FDA ruling, the Justice Department posted online its decision ruling that the Postal Service can legally deliver abortion medication sent through the mail, even in states where abortion is banned. Other mail carriers, including FedEx and UPS, have also been cleared to deliver the pills. This latest ruling came as some states continue to clamp down on self-managed abortions, driving people seeking abortions to increasingly risky measures.

Written by Eliza Siegel

Republished with CC BY-NC 4.0 License; this article was copy edited and retitled from its original version

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.