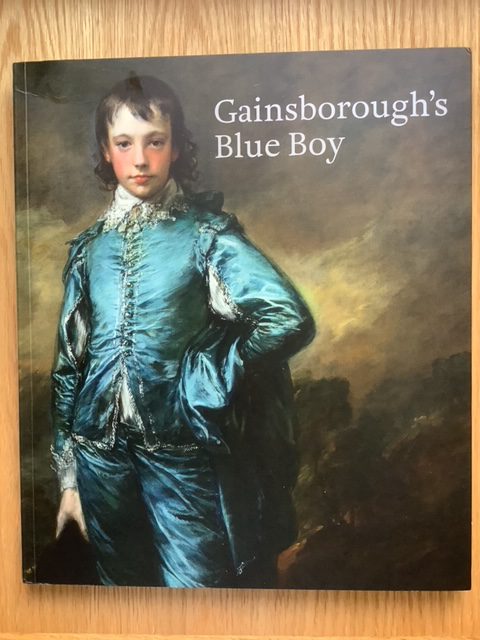

It has been nine weeks since The Blue Boy left The Huntington Art Museum’s Thornton Portrait Gallery for a journey back to its birth home. On January 25, 2022, one hundred years to the day the painting left England forever, The National Gallery in London opened an exhibition of the works of celebrated English painter Thomas Gainsborough called ‘Gainsborough’s Blue Boy: The Return of a British Icon.’

For the gallery, it was a much-anticipated event that was years in the making. In the catalog of the exhibition, The National Gallery Director Gabriele Finaldi, writes that initial negotiations about the possible loan of the painting held between Lord Rothschild and representatives of The Huntington began in 2015 – three years before either Karen Lawrence (The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens president) and Christina Nielson (The Huntington’s Hannah and Russel Kully Director of the Art Museum) assumed their current posts.

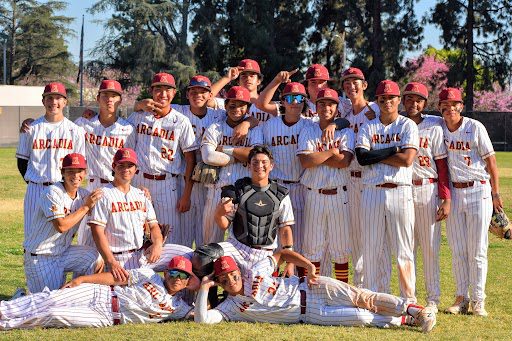

The Huntington hired its first conservator, Christina O’Connell, in 2013 and one of her initial projects was a survey of the art collections. In 2017 she planned and undertook ‘Project Blue Boy,’ the first technical examination and conservation work that was done in public view. A special satellite conservation studio was set up in the west end of the Thornton Portrait Gallery for the year-long exhibition, from September 22, 2018 to September 30, 2019. More than 217,000 people – many of whom traveled several miles – came to see it. Several habitués to The Huntington speculated that the possible loan was the impetus for the conservation work.

That The Blue Boy has reached an iconic stature is demonstrated by how much attention and scrutiny it invites … and how people react to any news about it. In 1921, when British citizens learned that the second Duke of Westminster sold The Blue Boy to an American industrialist, protests broke out in the streets. When it was on view at the National Gallery for three weeks in January 1922, approximately 90,000 people – some of whom wept – queued to see it for the last time.

The National Gallery’s then director, Sir Charles Holmes, nostalgically inscribed ‘Au Revoi, C.H.’ at the back of the painting. O’Connell, when she worked on ‘Project Blue Boy,’ very thoughtfully made sure it was also preserved. While that wish was granted a century later, Nielsen assures that it didn’t influence The Huntington’s magnanimous loan. “Strictly speaking, we agreed to lend only after lengthy consideration of a number of factors. But it makes part of a great story!”

In a reversal of events, when The Huntington announced in July last year that The Blue Boy was traveling to England for an exhibition, a wave of comments and views erupted. Art enthusiasts and museum-goers – some of whom didn’t have professional art experience – had as strong an opinion on the matter as art critics and experts. L.A. Times art critic Christopher Knight expressed incredulity that The Huntington went against the advice of the very experts the institution consulted. He said conservation experts believed the painting was too fragile to make that arduous journey. The Huntington, just as quickly, issued a response that refuted Knight’s claims. In the letter, Lawrence and Gregory A. Pieschala, The Huntington’s Chair of Board Trustees, mentioned that the institution convened a second panel of conservators and curators in 2019 when most of the conservation work was complete and it advised that the painting could be lent safely.

On both sides of the Atlantic, news that The Blue Boy will be back in its home country for a 16- week exhibition – from January 25 through May 15, 2022 – garnered extensive publicity. Articles were written about The Blue Boy’s storied history and how its image has been used and appropriated.

The exhibition is expected to draw large crowds as well. While the National Gallery will not release visitation data until the exhibition has closed, Christine Riding, curator of the ‘Gainsborough’s Blue Boy,’ provided an anecdotal report. “The Blue Boy is proving incredibly popular with National Gallery visitors. From the very first day the exhibition opened, with a long queue of people keen to be the very first to say hello to him on his return, we’ve experienced large amounts of people each day eagerly making their way through the Gallery to see this exceptional loan.”

However, much like many renowned works of art, The Blue Boy’s popularity came long after the painter’s death. Riding writes in the exhibition’s catalogue, “One of the ironies of art history is that Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy attracted little public attention (as far as contemporary sources relay) when it was first shown at the Royal Academy in 1770. Yet 150 years later, when it was sold to the American tycoon Henry E. Huntington, it was one of the most famous paintings in the world.”

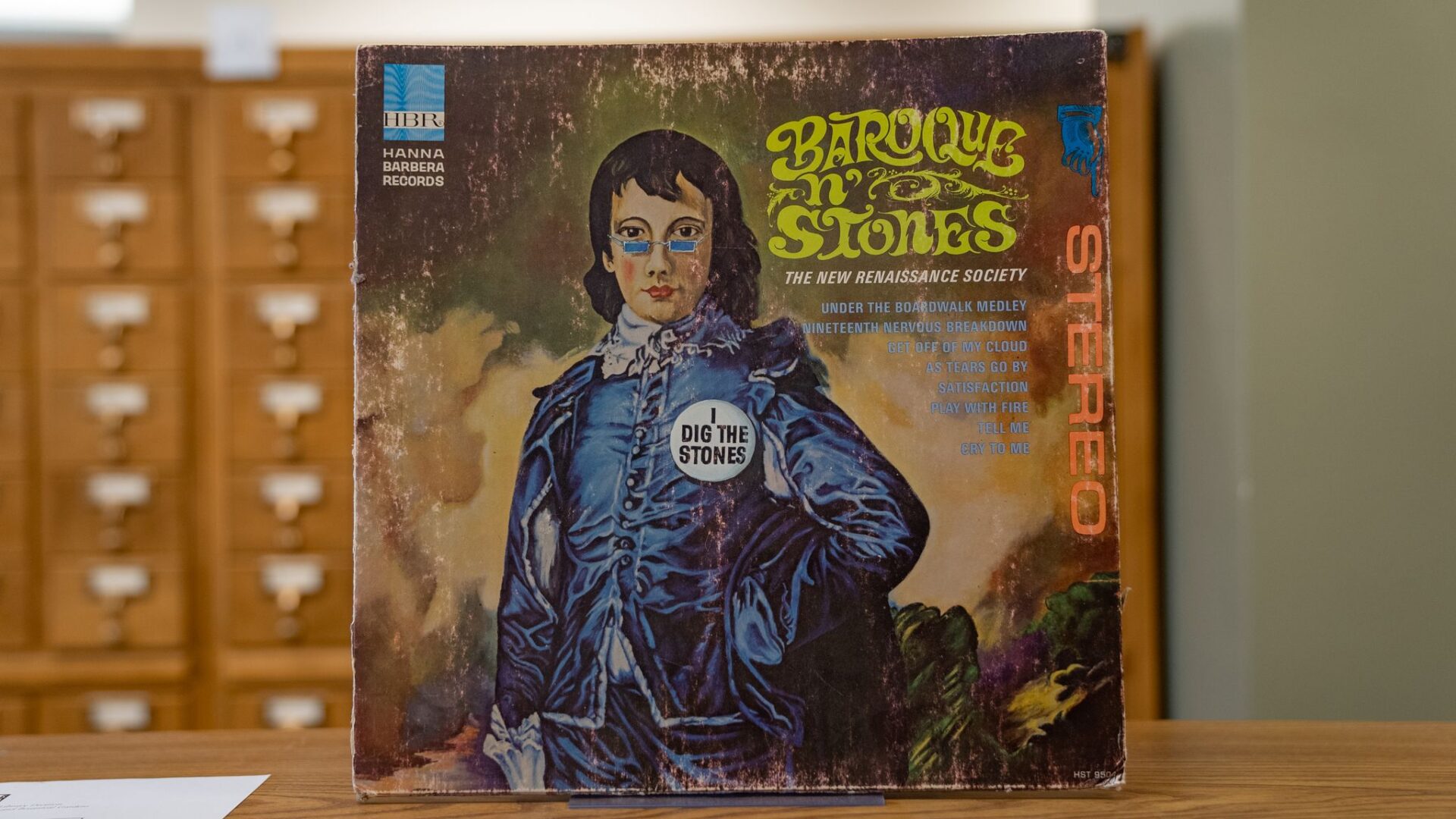

Indeed, images of the Blue Boy has appeared on everything from chocolate tins to folding screens, as fashion historian and curator Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell chronicles in a blog titled ‘Blue Boy Mania: How Gainsborough’s Masterpiece Colored Pop Culture.’ In it, she records the painting’s history and its appeal to advertisers, entertainers, and interior decorators.

Anyone who has seen The Blue Boy identifies with it in some ways. And just like beauty being in the eye of the beholder, the painting stirs a different feeling or emotion in each of us. Leading up to the exhibition opening at The National Gallery, articles published in the U.K. demonstrated this. Matthew Wilson wrote in BBC Culture about its appropriation (or misappropriation) as a symbol for gay pride. Meanwhile, art historian Dan Ho paid a tribute to it in February for LGBTQ+ History Month. Jonathan Jones shared his jaded view in The Guardian that ‘it’s as a hokey vision of English art as a Disney cartoon of a fox hunt.’

Asked by email if the disparate sentiments expressed in the articles make people curious to see The Blue Boy, or if they take away from its mystique, Nielsen replies, “The painting has captivated audiences since it first went on display in 1770. It means something different to everyone who sees it, and that is part of its magic.”

Stories about The Blue Boy will be written in the decades and centuries yet to come. This gorgeous boy, who has inspired countless interpretations and conjured just as many images, could very well signify something else altogether to the generations after us. Some of the ways people relate to him and the painting may not be what Gainsborough originally intended. In Wilson’s BBC Culture article, he cites an art history professor saying “artists cede control of their creations once they are absorbed into the public arena.”

And, in essence, that’s the greatest gift artists could leave behind – for people to make of their artwork what they will. At the same time, it’s an assurance that their artwork will continue to be relevant.