View Winners →

View Winners →

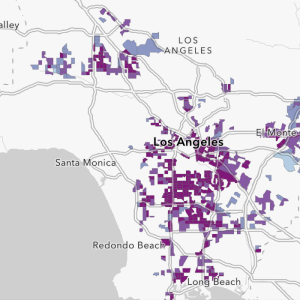

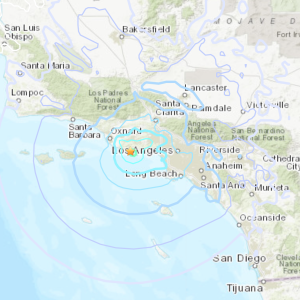

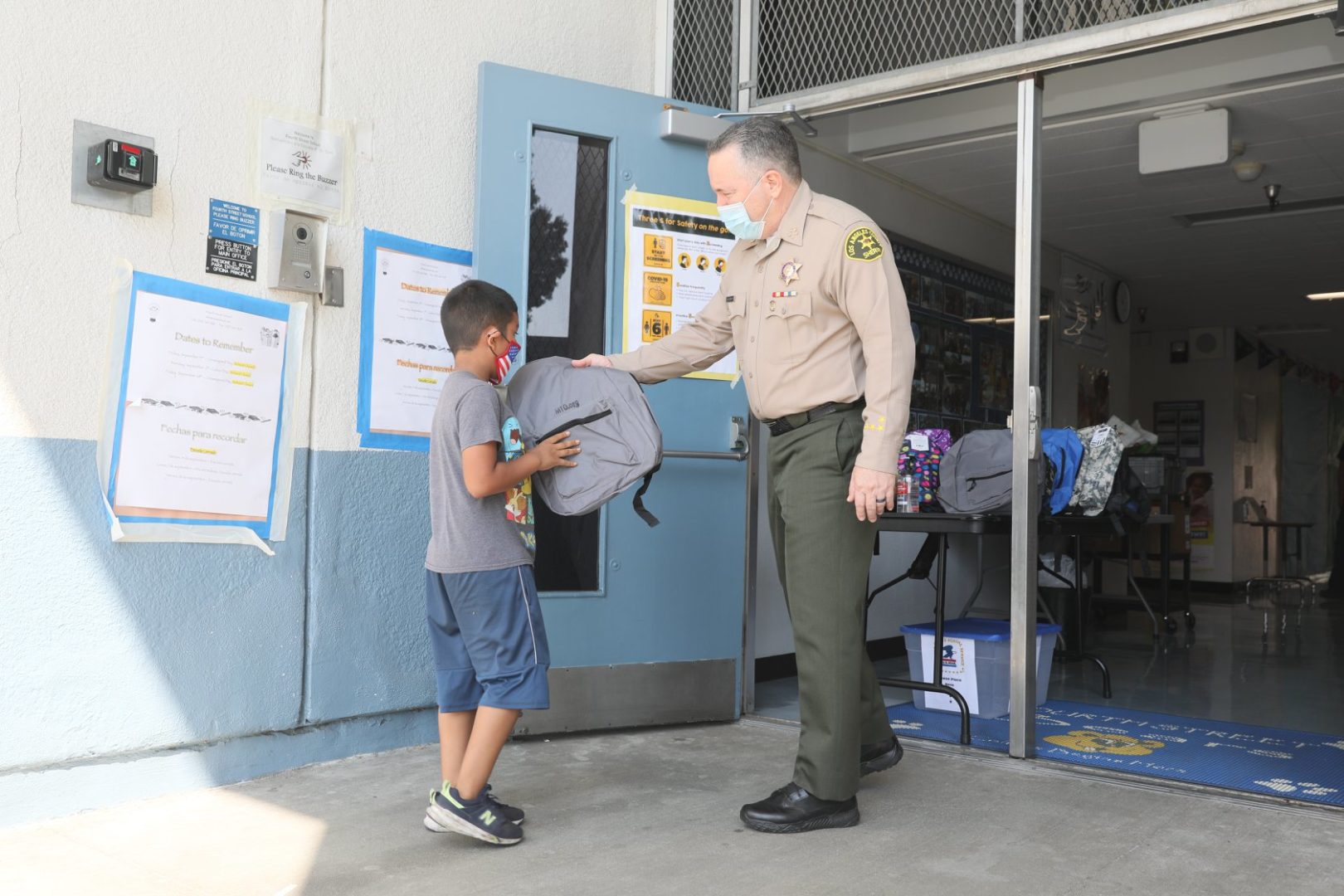

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously Tuesday to collect more data on the effect of having sheriff’s deputies on local school campuses, even as some school districts pushed back against changes.

On a 3-2 vote, the board also took back its authority to negotiate contracts for these services, rather than allowing the sheriff to hammer out deals directly with local school districts.

Supervisors Janice Hahn and Kathryn Barger voted against the move to control negotiations, reacting to school district representatives demanding local autonomy.

Supervisors Holly Mitchell and Sheila Kuehl were the co-authors of the motion proposing additional oversight of these contracts.

“Law enforcement presence on school campuses can have a negative impact on students,” Mitchell said, pointing to research showing higher rates of fear and anxiety among students and a disproportionate negative impact on students of color.

Kuehl said alternative programs, such as counseling and mental health services, would better serve schools.

“Enforcement does not prioritize the well-being of students,” Kuehl said.

Mitchell and Kuehl cited a survey by the National Center for Education Statistics, among other research.

“Researchers … find that schools with high security not only have more suspensions, but also a greater Black-white disparity in these suspensions,” according to the motion.

In a May letter to the board seeking renewal of current contracts, Sheriff Alex Villanueva and Undersheriff Timothy Murakami wrote, “Deputies assist the schools with the implementation of programs designed to help prevent school violence, provide a safe learning environment, and provide public safety,” including helping with emergency preparedness.

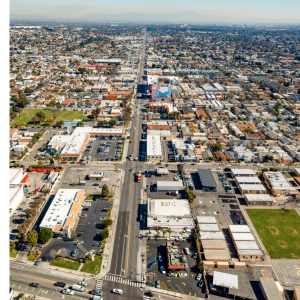

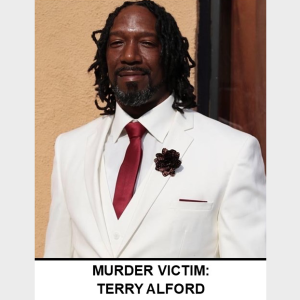

Laura Coholan, with nonprofit La Defensa, shared her experience as a middle-school teacher in South Los Angeles, where she said she had seen many young students removed from campus in handcuffs.

“This criminalization would not have happened in a predominantly white school district,” Coholan said, adding that incidents like this traumatized other students and urging the board to “completely remove any sort of law enforcement from school campuses.”

Despite such concerns, a number of school board members or trustees told the board they didn’t want their interference, arguing for local control and citing a productive partnership with the LASD.

“I can tell you by experience that Rowland Unified has had fewer behavioral problems and citations issued to students since we changed from a school-based police department to contracting (with LASD),” said David Malkin, a Rowland Unified School District board member who is also a licensed clinical social worker.

“We … actively partner with our local LASD stations to seek out a (school resource officer who) … is compassionate, a mentor and supportive. If the right officer is selected, that can build a bridge so badly needed between students and police.”‘

Mitchell and Kuehl insisted that the intent of the motion was not to take power away from school districts, but to offer more services to all students.

“This motion does not seek to second guess or disrupt the role of local school districts,” Kuehl said.

However, Hahn said many school representatives in her district had raised concerns. She said she wanted to ensure that local school districts could decide on their own whether or not to employ school resource officers.

“That should be their local choice,” Hahn said of districts that want to keep officers on campus. “That doesn’t preclude them from contracting with us for other resources … more school counselors, more mental health professionals.”

Despite insistence by Kuehl and Mitchell that school districts could still make their own choices, the board ultimately chose to split the motion into two parts before voting.

The Lynwood Unified School District earlier made the decision not to renew its contract for school resource officers and will use that $350,000 to fund counseling, a 24-hour mental health hotline and to set up a college fund for local kindergartners, school board president Gary Hardie told county officials.

Ivette Ale of Dignity & Power Now said students should be the ones consulted and argued that collecting more data was a waste of time, given the volume of existing research showing that students of color, particularly Black girls, are harmed by the presence of officers on campus.

“Subjecting children to the violence of law enforcement, even violence with oversight, is reprehensible,” Ale said.

The board also directed the Office of Diversion and Reentry to collaborate with school districts and community members on a plan that could “eliminate or reduce the need for law enforcement intervention” at schools.

The Sheriff’s Department has provided these services to some schools for roughly 23 years. Seventeen districts currently participate, paying the county nearly $8 million in total, according to the May LASD letter.