“We Are Here: Contemporary Art and Asian Voices in Los Angeles” was slated to open at USC Pacific Asia Museum (USC PAM) in March of last year but the coronavirus pandemic caused temporary closure of art galleries. While it was an enormous disappointment, it was a necessary mandate given the severity of the situation. We didn’t know it then, but all art venues would remain shuttered for what felt like an interminably long time.

The museum’s announcement that it will reopen to the public on May 29 was welcome news for all art enthusiasts. “We Are Here,” which has only been accessible online, will have its final week on view with in-person visits. The news also couldn’t have come on a more fitting occasion – AAPI Heritage Month. These artists and the experiences mirrored in their work reflect Asian American and Pacific Islanders’ many contributions to our country’s history, culture, and achievements.

“We Are Here” is curated Dr. Rebecca Hall, who has a PhD in Southeast Asian Art History from UCLA with a specialty in Buddhist art and textiles in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. After receiving her doctoral degree, she lived in Southeast Asia for a while doing research and teaching. She then moved back to the United States and taught in L.A. and Richmond, Va. She also had a curatorial postdoctoral fellowship at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. More recently, she taught at Santa Monica College and Pasadena City College.

Because of her expertise, Dr. Hall was hired as a guest curator at USC PAM for an exhibition called “Ceremonies and Celebrations: Textile Treasures from the USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection”. It was up in the special exhibition galleries from September 2018 until January 2019, following her designation as a full-time curator in July 2018.

Prior to the pandemic, Dr. Hall graciously agreed to give a private guided tour while she discussed her vision for the exhibition and talked extensively about each artist’s background.

“I have been putting this together for a little over a year now,” Dr. Hall commenced. “It was grounded in my conviction that we have this incredible collection of art from the Asia Pacific world. And that world extends beyond the geography of Asia and the Pacific which we typically think of, but really encompasses the diversity of Los Angeles itself. As a person who’s not from L.A., but has lived here off and on since 2002, I wanted the opportunity to celebrate the diversity of our Asian and Pacific population.”

Recounted Dr. Hall, “I didn’t have any connections to contemporary artists in L.A. but I know we have one of the most wonderfully diverse and densely populated areas of people of Asian heritage living in one of the most creative cities on earth. I knew my task would not be that difficult and I just began to explore. Once I decided to develop an exhibition featuring the work of L.A.-based Asian artists, I started googling and looking at galleries, exhibitions, and artists’ websites. I made a long list of artists, and chose the seven I was most interested in and whose work I was most drawn to. It was a slow process at the outset but it was interesting and I learned a lot about artists in Los Angeles.

“As part of the exhibition, we also have these videos of three- to five-minute conversations with the artists that add layers of understanding. One of the joys, for me, in putting together this exhibition, is how brilliantly and clearly each of these artists articulate their vision in their work as well as when they talk about it. Furthermore, they’re very dynamic artists – each one works in different media and from a different perspective.”

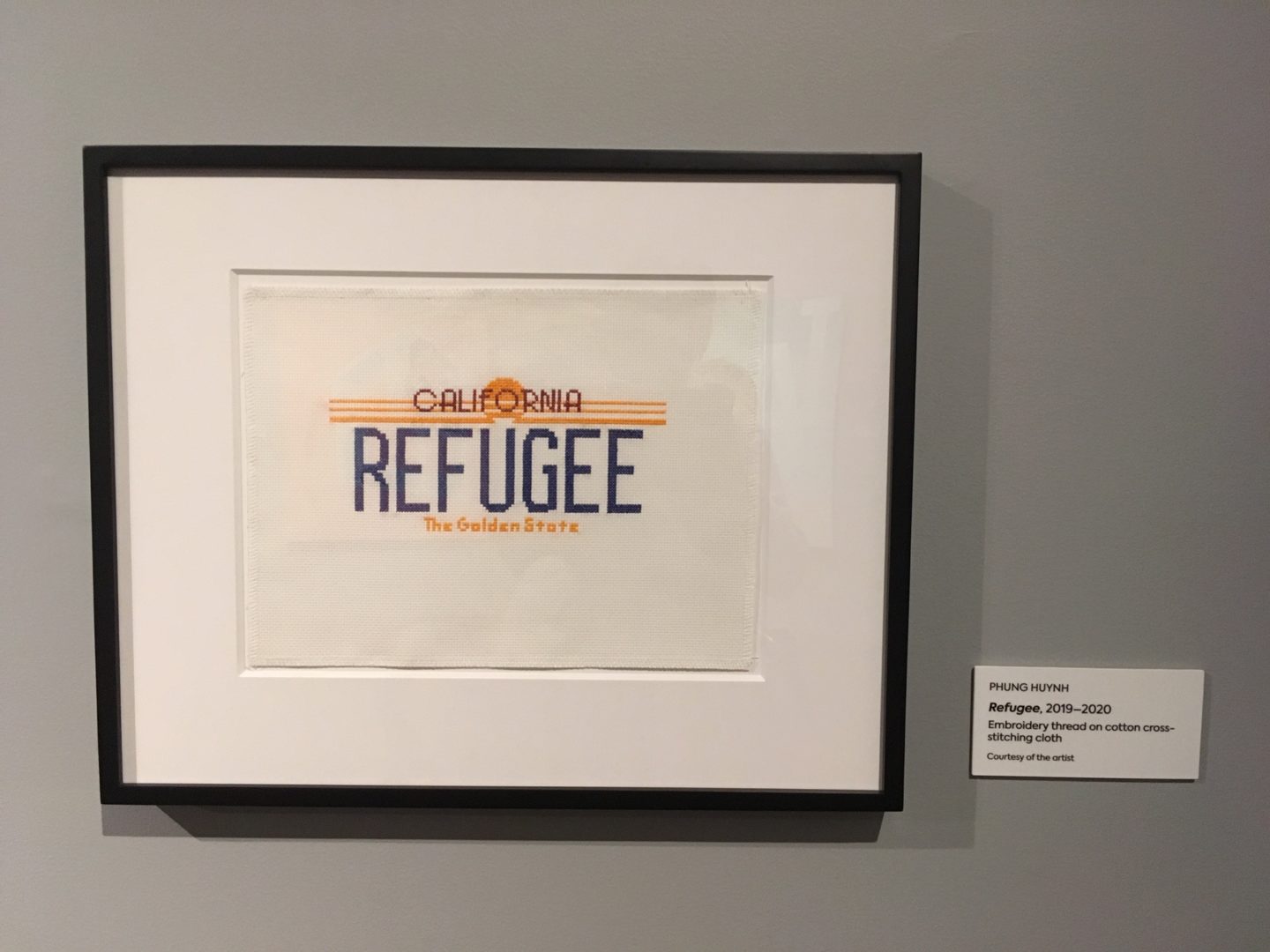

The exhibition is organized by artist – there is a small display with a short introduction about each, with an accompanying detail about their work. As you walk in you’ll enter the space of Phung Huynh. Dr. Hall described, “Phung is a refugee from the Vietnam War but her history isn’t as straightforward as just that. Her mother is Vietnamese; her father is Cambodian who fled Cambodia into Vietnam where he met her mom. Her mother’s side of the family is actually ethnic Chinese who moved to Vietnam as refugees from China. She moved to the United States when she was a toddler and, living in Chinatown, was pushed to learn Chinese; it became a part of who she was. So her initial works of art and what she had shown up to this point were about how we perceive Chinese people and culture and how Asian American woman are pressured to modify their appearance to acceptable American standards. When I met with her, she had actually just been embarking on artwork that looks at her experiences as a Vietnamese and Cambodian refugee.

“When you come into the gallery you’ll see right away something iconic – a dozen pink donut boxes that she’s using as a canvas for portraits. Each portrait is that of a refugee from Southeast Asia who exemplifies power and perseverance: herself as a toddler; her parents; an artist; a chef; and some local personalities she interviewed, including someone who survived the Khmer Rouge through his art; and a documentary filmmaker who now lives in France.

“She created a baker’s dozen and on one wall is a portrait of a 13th person who isn’t a refugee – Mister Rogers. He was the one who made her and her family feel welcome in the United States and helped them to learn English. I think a lot of people can identify with that compassion he showed everybody and his lack of judgement in the way that he helped people see that they’re all Americans. He has a warmth that we should all aspire to.”

Pink donut boxes reference the donut shops that Cambodian refugees opened to build a new life in Southern California after they fled the genocide. Huynh’s display of cross-stitched license plates, meanwhile, are souvenir key chains that kids going to theme parks can buy that signifies inclusivity and an opportunity for all Americans to find their names on these mementos.

The next artist is Ann Le and she has twelve pieces in the show.

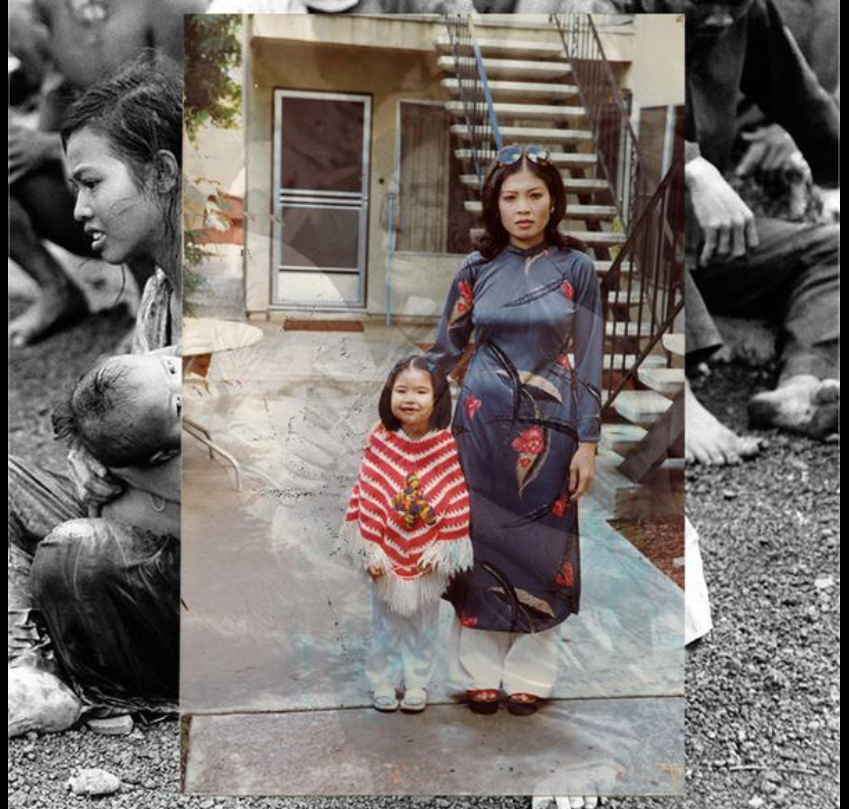

Dr. Hall expounded, “Ann was born in the United States to Vietnamese refugees. Growing up in a Vietnamese refugee community with her family left a lot of questions for her about who she was and why she was in this country. But her conversations with her family never directly touched on the war, its effects on them, and the reason they were refugees. I think she realized it was most important for her to articulate that point of view. She wanted to give voice to that experience and found a way to do it visually.

“Ann’s father was a photographer in Vietnam and he continued that interest in America. She has an archive of family photographs and her vision really came together when she looked at her family album. She took the photographs, collaged them on the computer, and layered them to create this juxtaposition that talks about war and loss, family and memory, in an incredibly compelling way. These are all members of her family in Vietnam and she put those photographs in front of typical Southern California middle class households to think about the disconnect, or connection, depending on your perspective, of who they are. She bridged that gap of what they would have if they were in California, or what they would have if they were in Vietnam.

“She has done a lot of research about the Vietnam War and wrapped that research into her work as well. She shows photos of her family placed together with imagery of the war – it’s a very strong statement. There are some subtleties but everyone sees and understands what she’s trying to get at. She’s very aware of the need for that conversation to take place.”

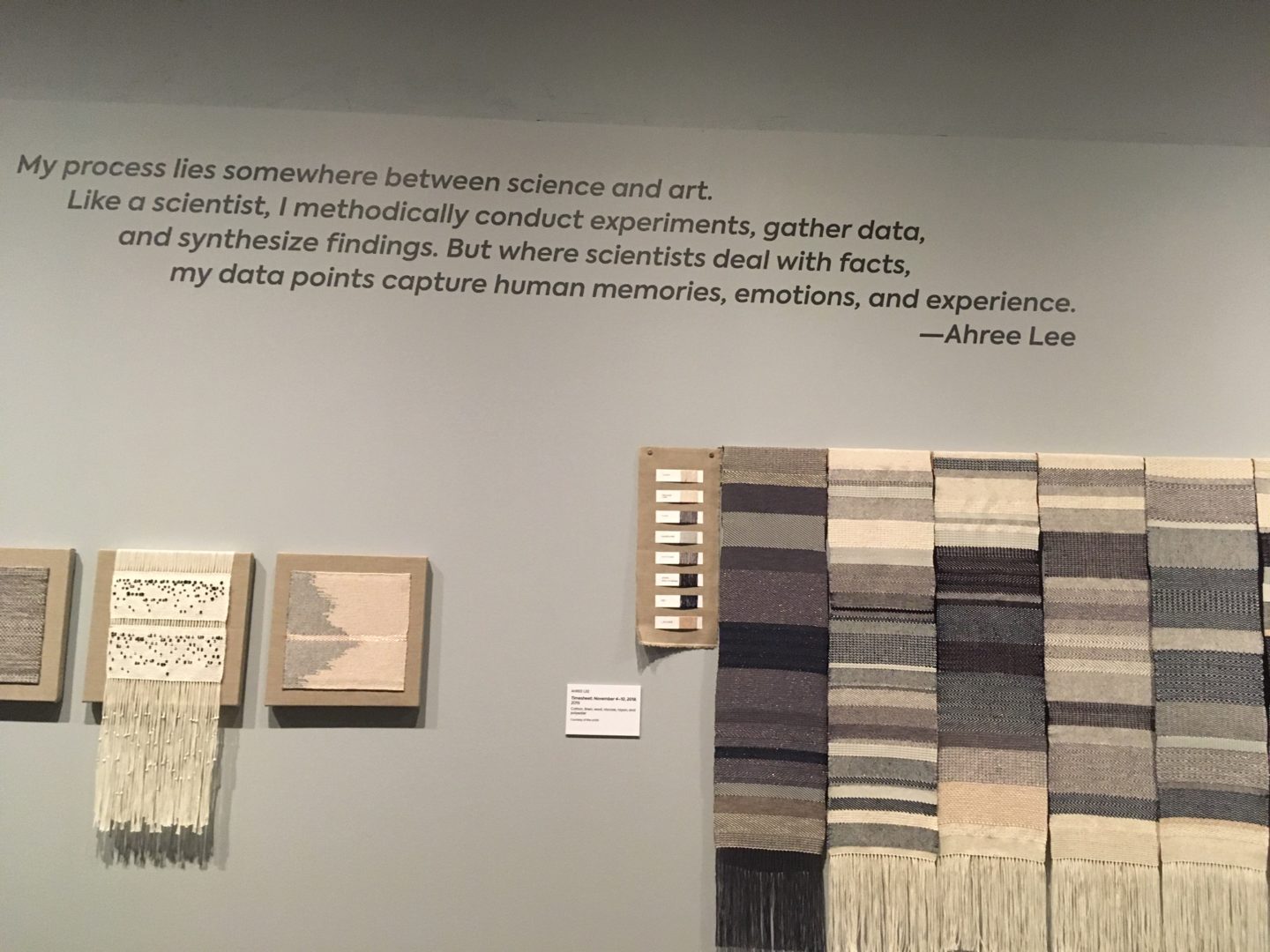

Dr. Hall introduced the next artist Ahree Lee and her work, “It was actually this video that drew her to me; I find this to be a very emotionally beautiful experience. It’s called ‘Bojagi’ (Memories to Light) which she created when she was resident artist at Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. She collected home videos and films from members of the Asian community in San Francisco doing just regular, mundane activities like visiting Frontier Town or going to the beach for a picnic, that aren’t important enough to be represented in mainstream media. She looked at human memories, emotions, and experience and then determined what was missing – in this case, the Asian-American experience – and put that into her work. What she came up with is a video that she called Bojagi, which is a Korean hand-quilted cloth that mothers would make for their daughters when they were going away to be married and got passed down over generations.

We then approached the next two displays which Dr. Hall explained are a totally different body of work that’s very new for Lee. She learned to weave when she became fascinated with the connection between weaving and computer technology. Her resulting artwork reveals a history that somehow got buried – that computer coding was based on loom technology and the pioneers of early programming were women. But when computer technology turned into a hugely profitable enterprise, it became a men’s field and women were shut out of the scene. She created a piece called ‘Ada,’ after Ada Lovelace, who was the first computer programmer in the 19th century, which physically and visually connects to that past and brings women’s labor into the discussion.

The other piece is composed of seven different weavings demonstrating her own labor. It’s one week of time in 2018, wherein she showed which portion of her day was spent on each activity – personal care, food, housework, childcare, non-household work, art, and leisure.

Walking to the space of Kaoru Mansour, Dr. Hall declared, “I love Kaoru’s work. You look at it and you just want to take it home with you. Growing up in Japan, Kaoru was discouraged from becoming an artist. When she moved to America, she started taking art classes and found her voice as an artist. The fact that she’s able to work every day on something that expresses who she is makes her happy. And that joy shines through in her work; she’s playful.

“Kaoru crafts her own visual language and doesn’t restrict herself – she moves through what’s interesting to her. She comes up with an idea, like heavy things hanging from a string, and she places the strings on the canvas. She falls in love with doilies and pompoms and creates art from those. She is active outdoors and in nature, and she integrates that in her work. If she’s thinking about family and her relationship to people, her work pivots in that direction.

“Her artist’s statement ‘If I can represent my character in the artwork, then I feel that I have successfully created an honest piece,’ is spot on. It perfectly describes her joy, her love of life, and her love of making art … and it spreads. People walk in this gallery and they love it – they feel excited.”

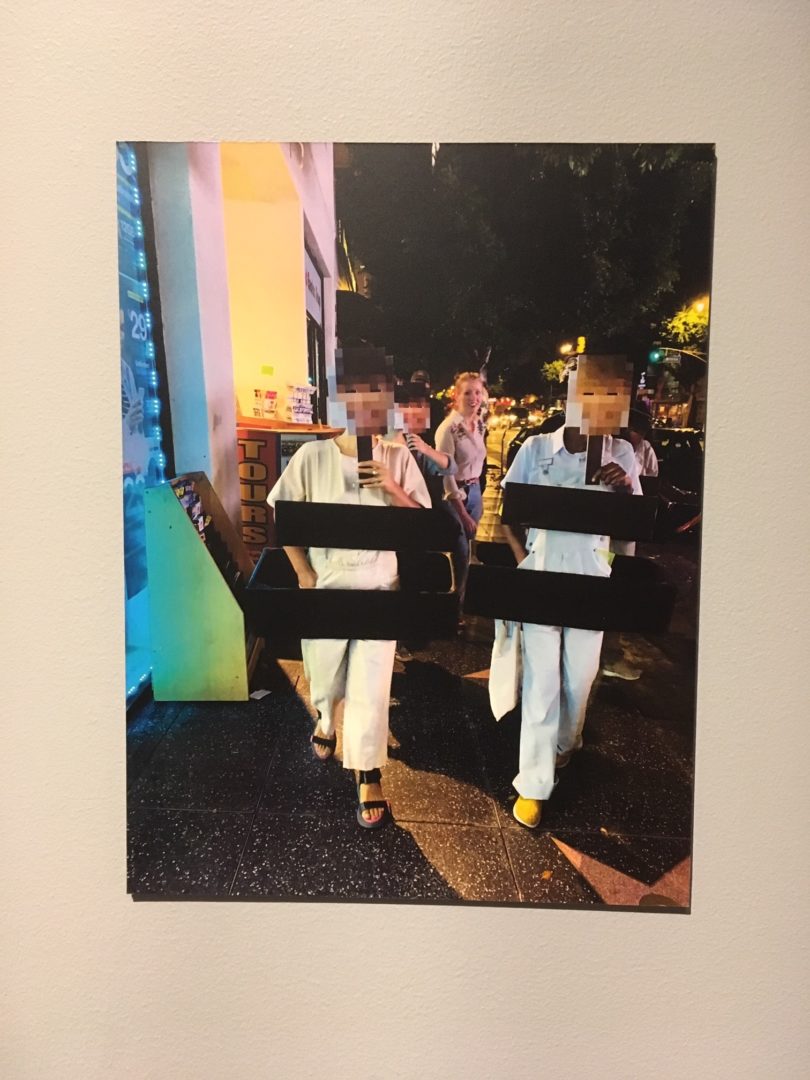

“Reanne Estrada‘s art is a little bit more difficult to explain,” Dr. Hall confessed as we reach the next display. “But I could not be more thrilled that she’s in this exhibition. She works very eclectically; she has both a collaborative and an individual art-making process. All of her work that we show here are part of a single idea – surveillance and security systems and how we function within something we aren’t actively a part of – we’re being watched all the time by cameras.

“She did a performance piece on Hollywood Boulevard in September 2019 in which she used prophylactics to obscure people’s gaits from being recorded by security monitors to identify who they are. She underscores the fact that surveillance is something that we have become so passive about. She is the only artist whose work carries over into our permanent collection – she created an audio tour of the Pacific Asia Museum that talks about surveillance and how it’s everywhere, but it is necessary because we’re protecting priceless works of art. But maybe when you leave, you’ll think about how surveillance cameras invade our privacy.

“Related to that is this website called ‘People Who Don’t Exist’ which shows how computers can harvest images of people who aren’t real but look real. She talks about how we lose control because of all the technology around us and finding ways to reassert ourselves.”

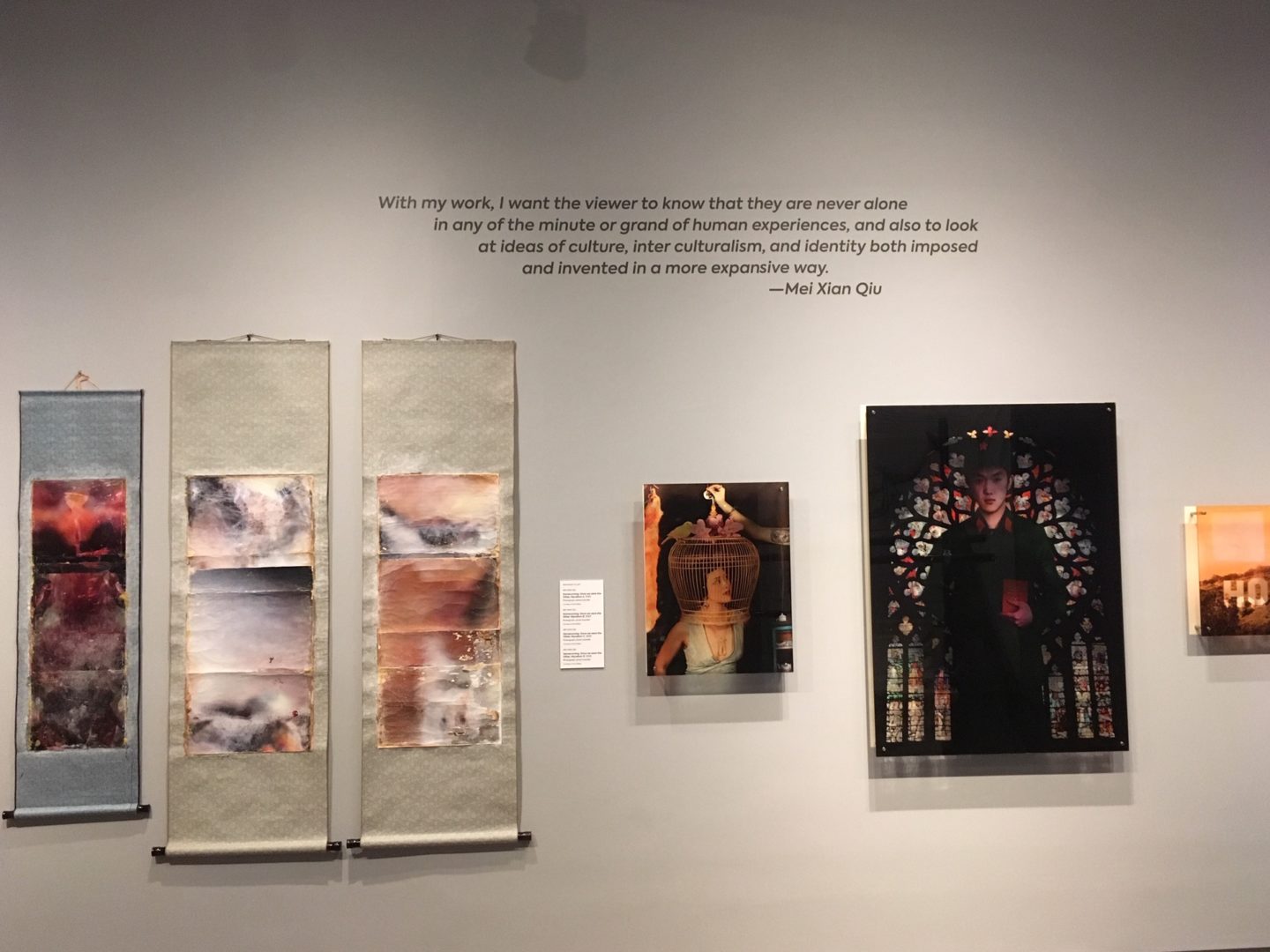

In the final gallery, visitors will see the works of two artists – Mei Xian Qiu and Sichong Xie.

Dr. Hall said about Qiu, “Mei is an ethnic Chinese woman born in Java. Her family has been in Indonesia for several generations since the 19th century where there’s a divided relationship between the Chinese and the Indonesian population. When she was born, she was given three different names by her family – a Chinese name, which was illegal according to the Indonesian government; an Indonesian name, which was required by the Indonesian government; and an American name, in anticipation of any possible future – in an embrace of her heritage. Her family fled to the United States to escape the anti-Chinese riots in Java. Her grandparents still live there, hence, Mei has been going back and forth between Indonesia and the United States with her family since her childhood. Her perspectives emanate from her as a Chinese, Indonesian, and American woman trying to figure out how she fits into all of this.”

“We’re showing different series of Mei’s work,” continued Dr. Hall. “The first one is an ongoing series she’s been doing for several years now called ‘Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom.’ It is a play on a 1965 Mao speech ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom’ that saw arts flourish but subsequently got artists persecuted. She’s exploring how we think we have freedom of expression, but maybe we do not.

“It is a playful, yet serious look at the possible Chinese invasion of the United States. She’s toying with perception and the relationship between the Chinese and the United States. For instance, in this piece ‘Hollywood Land’ from 2012, the models she used in her work are actually people who would have been persecuted under Mao’s regime – intellectuals, writers, and artists. The apparel that they’re wearing, like military outfits, were from the photo studios in Beijing that people would go to mimic the Red Army or Red Guard.

“Mei’s second series is about the homeland. This one is called ‘Homecoming: Once we were the Other,’ about a Chinese woman going home who felt a disconnect between herself and her environment. She is questioning who this woman is with multiple identities in connection with the trash in the street. So she began collecting it and making art from that which asks ‘Who am I as a Chinese woman and how do I connect with this material?’ ‘How do I excavate Chinese culture and that Chinese side of myself?

“There’s always apprehension when she goes back to Indonesia because of the ongoing tension between the Chinese and the Indonesian people. It ebbs and flows – there’s violence and then everything seems fine. Using her Indonesian name Cindy Suriyani, she created a piece ‘Dewi Cantik’ (Pretty Darling) that shows a child’s and a woman’s bedroom, all nice and pretty but underneath, the threat of violence is always there. The cutout pieces are actually batik pattern because their family had a batik factory. This woman’s work changes depending on what she’s doing but they’re all around the idea of figuring out who she is with all these identities stemming from her having three different names.”

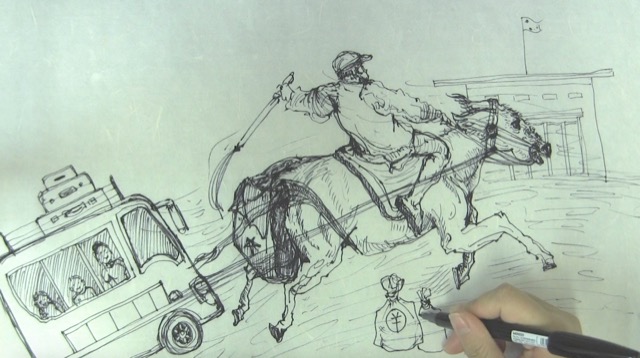

The seventh artist featured in the exhibition is Sichong Xie. Dr. Hall noted, “One aspect we’re touching on is that many people who live in L.A. are transplants and Sichong is an example. She was born in Mainland China, came to the United States initially as an undergraduate student, and found her voice as an artist. She eventually moved to L.A. for graduate school and decided to stay here.

“Sichong’s work is quite personal as well. She was very close to her grandparents; when her grandfather passed away, she found out he had drawn an illustration that had been published in the Beijing paper in the 1960s that had a political element to it. Because of it, he was thrown into a labor camp for two years and it had an adverse effect on her family. They had to relocate to Xian where she was born. The political cartoon was destroyed and nobody talked about it again so when she found out about it, she wanted to recreate it.

“What you see here came about from the chain of conversations she had with her grandmother in trying to redraw the cartoon. She would talk on the phone with her grandmother in Xian, and draw out how her grandmother would describe the cartoon and then would send it to her grandmother. Her grandmother would say, ‘That’s not right at all; the donkey wasn’t just holding the money bag, the donkey had the family riding on it, or there was a car, etc.’ And so, she has five different versions. It brings up questions about memory and about protection – ‘Is her grandmother misremembering it?’ and ‘Is she still afraid of what the cartoon would do for her granddaughter?’

“Sichong is a performance and an installation artist and we’re trying to show both. In this installation, she asks ‘Do donkeys know politics?’ and she’s done versions of it over the years and I really wanted it in the show because she came up with this way of presenting it. It’s totally new from everything she’s done before.”

Of the experience, Dr. Hall remarked, “I really enjoyed the process of working with the artists. It was definitely a conversation between me and each of them. We talked together to choose which pieces would be in the show and I tried to give them creative freedom and flexibility. Some artists were in the process of creating new works of art that are in the exhibition. A lot of that was just really good timing and for that reason I could not be happier. For example, Phung Huynh had explored aspects of being Asian in the US and the specific pressures placed on Asian women, but had only just started on her work examining the refugee experience when I first met with her. Reanne Estrada was just beginning her work on surveillance and created the site specific audio tour for USC PAM. And Mei Xian Qiu totally branched out from the photography series that people are more familiar with of hers, into the scrolls and the artworks exploring her experiences in Indonesia.”

The exhibition highlights women artists and Dr. Hall said it wasn’t by design. When she set out to find the artists, she discovered that they made what she found most compelling. Coincidentally, the show was scheduled to open in 2020 when there were many planned celebrations about women. Unfortunately, what would have been a commemoration of ‘The Year of the Woman’ was eclipsed by a year marked by untold worldwide devastation brought about by a pandemic. But it’s never too late to salute women and their accomplishments.

Dr. Hall clarified, “Personally, I’m not promoting it as an exhibition of women’s work, but this is at the point it should be because these artists do incredible work. But as a curator, I feel that the more important thing is I look forward to the day when having seven women of Asian heritage together in one show is not something out of the ordinary.

“Setting gender aside, however, the work of these artists engages with who they are as people and, often, who they are as immigrants or refugees. What I also love about their work is that they’re impeccably made. So even if you’re not interested in their narratives, I think that you can look at them and appreciate them for what they are. Furthermore, while their pieces are very specific, they express sentiments we can relate to and understand.”

Besides being a celebration of Asian artists’ achievements, and Asian women’s work in particular, it is being shown at a very opportune moment when anti-Asian crimes have reached immense proportion and publicity. For far too long, Asians have endured such hate crimes in obscurity and silence. Recently, they have been speaking up – urgently – and it’s time they were seen and heard.

Speaking as an Asian American, we should stop being invisible and voiceless. We’re no less important than others and our truths are no less significant than that of the next person’s. ‘We Are Here’ demonstrates that Asians are part of the human race but the Asian experience isn’t exclusive to Asian immigrants and refugees. The stories these seven women are telling are as profoundly personal as they are fundamentally universal.