Art Collectors’ Council members also purchase a rare Edward Burne-Jones portrait as a promised gift

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens announced this week that it has acquired a newly discovered painting by John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) depicting celebrated 18th-century British actress Mary Robinson, as well as works by British artists Alice Mary Chambers (ca. 1855–1920) and Madeline Green (1884–1947) and a set of screen prints by R.B. Kitaj (1932–2007), who, like Copley, was born in America and worked in England. The acquisitions were funded by the Huntington’s Art Collectors’ Council at its annual meeting last month.

In addition, longtime council members Hannah and Russel Kully purchased as a promised gift for The Huntington a painting by the 19th-century British artist and designer Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898). The painting, a portrait of the artist’s daughter, had been kept in the family since it was painted around 1888.

“This year we cover 200 years of British art history and bridge the Atlantic, celebrating the interconnected web of American and British art,” said Christina Nielsen, Hannah and Russel Kully director of the Art Museum at The Huntington. “In this group are masterpieces, rarities, works by underrecognized female artists, and works that tie together different collection areas at The Huntington in intriguing ways. Together, they amplify our collection’s strengths and further its reach into the 20th century, all thanks to the generosity of our Art Collectors’ Council. To the Kullys—words fail to express the depth of our gratitude for their indefatigable commitment to The Huntington’s art collections. With this Burne-Jones portrait, we will be able to share with visitors a rare and arresting work that expands our great William Morris collection to reveal a very personal look at his artistic partner.”

“Robinson in the Character of a Nun” is a cabinet portrait, perhaps commissioned by an admirer, of one of Britain’s most famous actresses of the late 18th century. Lost for generations until it was sold in 1999 at auction as a French painting of an unknown sitter, the newly identified work portrays Robinson in her role as Oriana in George Farquhar’s comedy “The Inconstant; or The Way to Win Him,” which she performed on the London stage in the spring of 1780. In the course of the play, Robinson’s character engages in a series of ruses—dressing as a nun, feigning madness, and finally disguising herself as a pageboy—to win the heart of her love interest.

The portrait was painted just a few years after Copley, who had already established himself as a leading portraitist in colonial America, moved from Boston to London to test his skills at the Royal Academy, and at the height of Robinson’s career. Around the same time, she sat for four of Copley’s professional rivals—Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, George Romney, and John Hoppner.

In the painting, Copley’s talent for rendering likeness and dress is on full view, with the darks of the nun’s habit set off by the painter’s incomparable use of gauzy whites. A beam of light through the window illuminates the fine features of the sitter’s face, highlighting her hands and the wooden cross laying across her lap.

Acclaimed by many to be one of the most beautiful actresses in England, Robinson was also a popular poet, novelist, playwright, feminist thinker, fashion trendsetter, and, most famously, mistress of the Prince of Wales, later George IV. The Huntington’s Library holds a renowned collection of materials related to the history of London theater and British literature that includes many of Robinson’s published and unpublished poems, novels, plays, and her posthumously published autobiography. The painting also serves as a complement to The Huntington’s American-made Copley, a portrait of Sarah Jackson (ca. 1765), and a later work from his British period, “The Western Brothers” (1783), both displayed in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. The Robinson portrait will go on view in the Huntington Art Gallery, among a collection of British portraiture.

Burne-Jones was among the most influential artists of his day. A friend and collaborator of William Morris, he was a designer of stained glass, decorated furniture, and textiles. Hundreds of working drawings relating to his design accomplishments are held at The Huntington, as well as one of the most popular installations in the Huntington Art Gallery, a two-story-high stained glass window, the “David Healey Memorial Window,” which he designed for the Unitarian Chapel, Heywood, Lancashire, around 1898.

Burne-Jones was also a painter, associated with both the pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement. His oil paintings often explore themes of faith, chivalry, and love through the lens of medieval or Renaissance art and are marked by a dreamy, otherworldly quality. With its restrained composition and harmonious palette, “Portrait of Margaret Mackail,” which depicts Burne-Jones’s beloved daughter, is typical of his style. Last owned by the sitter’s great-granddaughter, the painting has never been exhibited or published. It will go on view in the Huntington Art Gallery alongside other works from the British Design Reform period.

Though she was well connected among London’s pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts artists, and regularly exhibited her work at the Royal Academy, Alice Mary Chambers was a Victorian-era artist who only recently is emerging from obscurity thanks to the recent definitive identification of the monogram with which she signed her work and a 2018 scholarly article on her life and career.

Chambers was a friend of infamous art dealer Charles Howell, and correspondent of James McNeill Whistler; and her interest in the work of William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (co-founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) is evident in “Portrait of a Young Woman.” Worked in sumptuous strokes of red chalk, the delicate figure looks up from under heavily shaded brows in an expression that lends her a dreamy quality typical of Burne-Jones’s work. The leafy background of the portrait is reminiscent of Morris’s wallpaper designs, and Chambers consciously modeled her monogram in the lower left on that of Rossetti. The portrait adds a rare example of a female artist’s work to the collection of more than 12,000 British drawings at The Huntington.

Joseph Duveen, the famous art dealer who helped Henry and Arabella Huntington acquire the works that became the core of The Huntington’s art collections, championed Madeline Green, acquiring her painting “The Future” (1925) in 1927 and giving it to the Manchester Art Gallery that year. Green also won awards at the Royal Academy and exhibited at the Paris Salon and Venice Biennale. But her work is practically unknown today, and only recently reemerging through a new publication and recent exhibition at Gunnersbury Park and Museum in London.

With the self-portrait “Miss Brown,” Green playfully puns on her last name to present herself in the guise of another. Throughout her career, Green played with the concept of portraiture and self-portraiture, depicting herself as a mother, a wife, a dancer, an actress—alternately fierce, timid, provocative, but always appearing intelligent and with a pronounced independence. Miss Brown is dressed as a costermonger (fruit and vegetable seller) with apron and checkered scarf. (In other paintings, Green depicts herself dressed as a male costermonger.) Green’s technique involves rich layers on the canvas, with some areas so thinly painted as if to evoke watercolor, and others thick with impasto. Green explained how she accomplished the unique depth and texture of her painting, saying she worked “in body colour [opaque watercolor] underneath and glazed with pure colour and oil. I always paint in this way and although it takes rather a time, I don’t think the same effect can be obtained otherwise.”

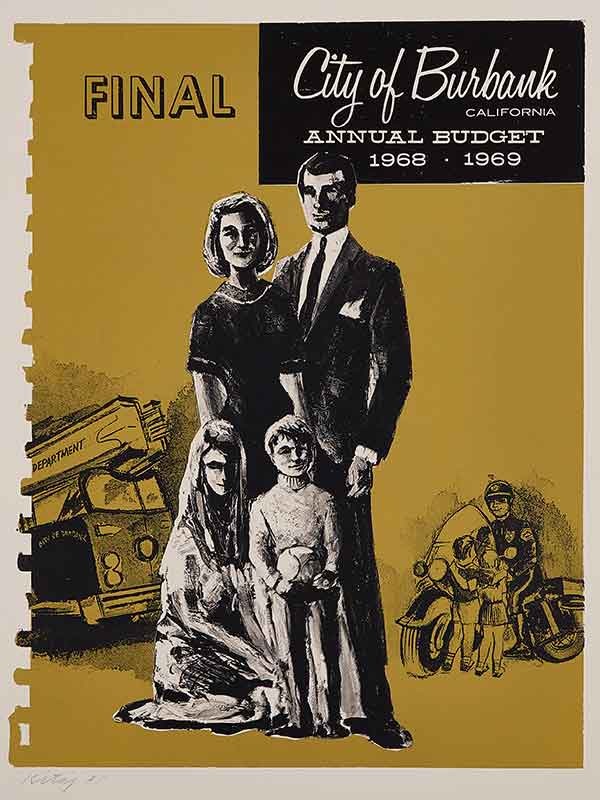

Kitaj, an American, was one of the most prominent figures of the London art scene during the 1960s and ‘70s. As a young man, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill to study art in the U.K., and ended up staying there for nearly 30 years, only occasionally returning to the U.S. for short periods to teach.

Kitaj is credited with coining the phrase “School of London” to describe his circle of figurative painters that included famous names such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and David Hockney. In addition to painting, printmaking was a major part of Kitaj’s practice since 1962, when he was introduced to master screen printer Chris Prater at London’s Kelpra Studio. For Kitaj, printmaking, with its serial generation of imagery, had an immediacy that did not exist in oil painting. He called the practice “as close to spontaneity as I’ve ever managed to come.”

A portfolio of 50 prints, “In Our Time: Covers for a Small Library After the Life for the Most Part,” produced at Kelpra, reflects the interconnection of art and literature that is a major hallmark of his work. It reproduces the covers of books the artist had collected. As he recalled, “I combed bookshops and libraries, my own and those of friends, over a few years for memorable covers, for the look of them, their associations, variety, color, reverberations, titles, etc.” The acquisition includes an additional three prints representing book covers not part of the original edition.

“In Our Time” complements The Huntington’s growing holdings in the field of later 20th-century graphic and pop art, which include the work of Romare Bearden, Henry Moore, and Andy Warhol.