From the moment you enter the Metropolis for the American Contemporary Ballet, the space breathes intimacy. Situated in a secluded corner of Downtown Los Angeles, across from the Hotel Indigo, the warehouse-esque atmosphere feels more akin to a speakeasy than the stereotypical image of a traditional ballet.

Walking into the dimly lit, slightly smoky room surrounded by frosted glass windows, a wall of mirrors, and two grand pianos, it was apparent that I was in for an experience disguised as a performance. It is in that contrast between bourgeois ballet expectation and sultry reality where the American Contemporary Ballet announces itself and delivers.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B4OEAgCgSe3/

The first half of the performance, entitled Inferno, is a ballet unlike any I have ever witnessed. My image of the ballet has always been one of distance and dissonance, typically seated in the far recesses of a grandiose space, watching a series of dancers on a far off stage. Inferno takes this preconception and immediately turns it on its head, seating the audience mere inches from the stage—so close I was worried that my gangly limbs might trip up a dancer that came too close, cognizant of my feet crossed beneath me.

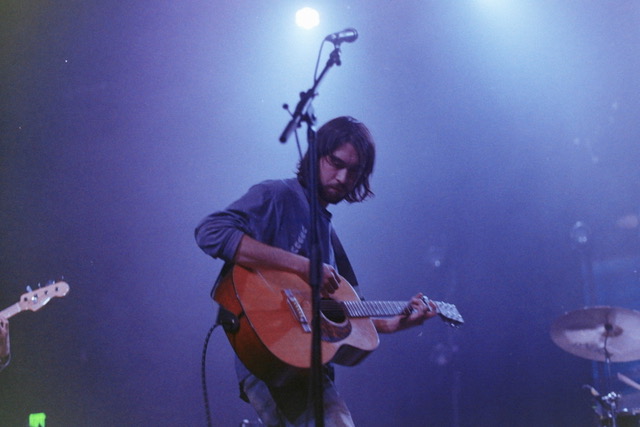

In the silent anticipation, the music begins, a chaotic and visceral composition by Charles Wuorinen, played by two pianists (Alin Melik-Adamyan and Naomi Sumitani) in tandem, the singular spotlight stage right turns on and the immersion begins.

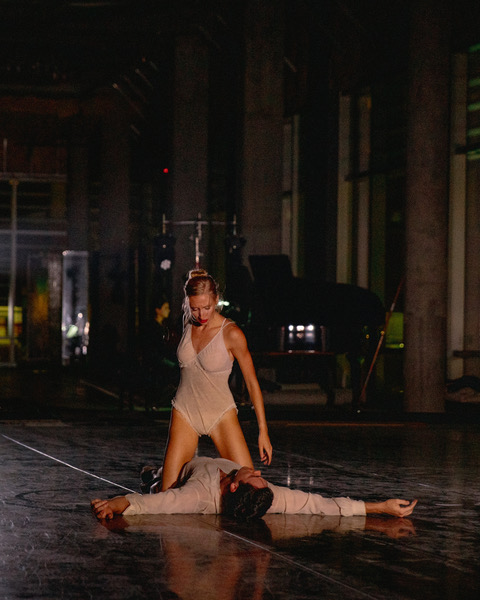

The proximity between voyeur and performer that Inferno embraces only heightens the sense of rapture. As the dancers each enter for their respective numbers from various sides of the stage (which is only a dark floor mat like the ones I remember from tumbling gyms and high school wrestling rooms) they creep into view under the light, often still partly in shadow—highlighting their movements and the tension between each dancer seamlessly. There are a few moments in Inferno that continue to haunt me the morning after—if not the entirety of the performance.

I am still haunted by the image of Joshua Brown as Virgil, the only male dancer in the production, carrying Carmen Callahan on his back around the stage; her nudity is only revealed when he tip-toes them both into the light. The raw intimacy of these moments lives in the striking tension of the audience’s proximity. Intimate involvement curbs the potential for the subjects to be sensationalized.

The performance’s sensuality moves from performative to visceral as the physicality of the dancer comes into full view. During each pause or elongated pirouette, the audience can see the shiver of muscle and hear every exhausted, yet composed, breath. Thus, the Inferno dancer moves from the art object to the human, creating an intimacy that, by the final act, had reduced me to tears.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B4P2Us8JjHG/

After Inferno, and a brief intermission (with complimentary red wine), the production shifts into Burlesque, a series of deeply sensual vignettes—performed entirely by female dancers. The sexuality that Burlesque implies in title alone is highlighted in the first act as the dancers trade their ballet flats for sparkling heels, an emblem of feminine “performativity” that intrigued me more than the nudity itself. The attention to the feminine is then simultaneously capitalized on and subverted as the dancers begin to perform a variety of abstracted strip-teases, the most shocking of which unfolds in the second scene.

As the singular spotlight dims, and the music slows, two male stage-hands carry out a single sheet of plexiglass, blurring the line between performance and production and creating a mixture of unease and fascination that foreshadows the BDSM inspired scene to come. Still shrouded in darkness, two female dancers approach the glass followed by a man (so shadowed that only his stature gives him away) carrying dancer Cierra Flood covered from head-to-toe in latex.

As the performance unleashes so does the dancer-as-gimp, slowly unraveled from her skin-tight covering by her two dominatrix cohorts. The first half of the performances in Burlesque live in this dimly lit and deeply sexual space. The second scene presented a woman (Brittany Yevoli), promptly walked out on a leash by Joshua Brown covered in nothing but leopard print body paint. Yet for all the shock-and-awe of these numbers, the American Contemporary Ballet exudes tasteful decadence under Artistic Director Lincoln Jones’ vision, elevating the visceral to a place of intimacy, making the scenes of dominance and submission feel no different than the graceful dances on pointe of Inferno.

In contrast and compliment to the first-half, the final vignettes of Burlesque shift toward the feminine in a way that challenges the positioning of the female body as a sexual object. In the final scene of the performance, dancer Cara Hansvick in a ball-gown and fishnets undresses in front of the audience, so close that the sound of satin against her tights meshes with the music itself.

The audience watches her as if from within her bedroom, after a long night out on the town, performing only for herself. In her wake, the voyeuristic element feels far removed from Hansvick’s relationship to her body and movement.

As the final layers of clothing come off, she reveals a set of bejeweled pasties as she saunters off stage—the dim light reflecting off the sides of her crystal clad breasts, a perfect and haunting metaphor for the experience of the American Contemporary Ballet.

ACB pushes the boundary between intimacy and abstraction with ease and grace. It is a show that you’ll want to see more than once. I guarantee, just like me, you’ll be thinking about the experience long after the final applause.

Inferno & Burlesque concludes on November 2nd following a Strange Halloween fundraiser, titled Hellraiser, featuring Dita Von Teese. Tickets are available at acbdances.com.