In Los Angeles County, freeways are a ubiquitous part of our surroundings. It’s hard to imagine a time when we traveled the expanse of the region on city streets. As population increased and more cars traversed the roads, freeways were constructed to make driving safer for people and areas more accessible.

The 110 Freeway, more popularly known as the Pasadena Freeway, is one of the oldest freeways, if not the first in the United States. The first section — the Arroyo Seco Parkway — opened to traffic in 1938 and the rest of the throughway opened in 1940. Today, there are several freeway interchanges that connect Los Angeles to various parts of California and other states.

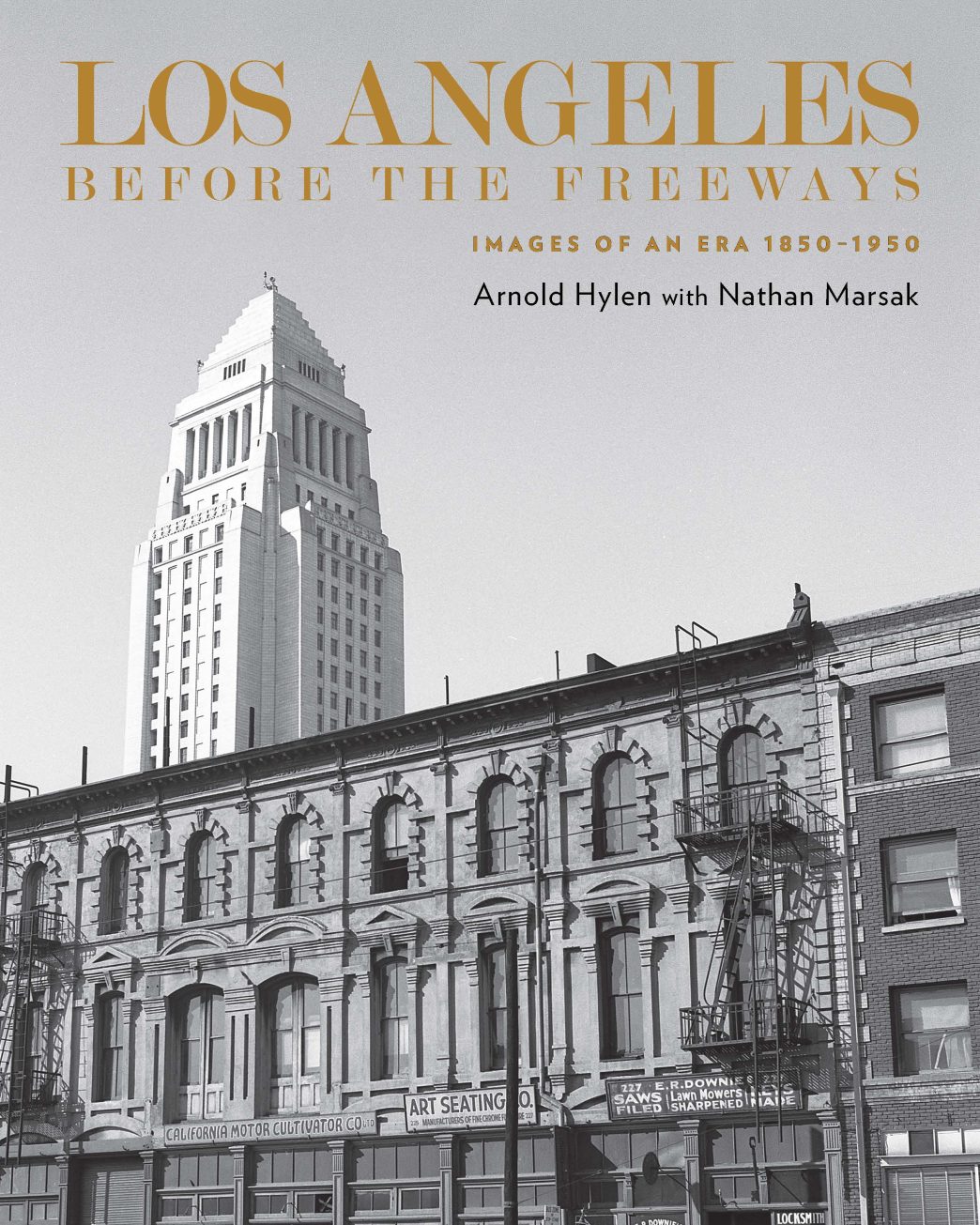

Countless buildings were demolished to make way for the construction of these freeways. The book “Los Angeles Before the Freeways: Images of An Era 1850-1950” gives a lush, visual tour of a Los Angeles that no longer exists — one of elegant office buildings and stately mansions that were razed in the name of “progress.” Originally published by Dawson’s Book Shop in 1981, it has become a cult classic among LA’s architectural historians.

Gorgeous black-and-white photos from Arnold Hylen that capture a forgotten era are showcased in the book. It has an original essay by the photographer that provides historical background and context for the time period. This new edition from Angel City Press, to be released on March 25, contains additional, never-before-seen photographs from Hylen and newly unearthed information from historian Nathan Marsak on these lost architectural treasures.

The stunning photography recalls an era when downtown Los Angeles was unspoiled by widescale redevelopment and retained much of its original character. Each page offers a glimpse of what the city used to be, before some of its architectural jewels were destroyed for the newer, more modern city that would soon follow.

Marsak discussed via email how he became an LA historian — despite not being a native Angeleno — and the upcoming book “Los Angeles Before the Freeways” and why it’s important to get it republished.

“I was born and raised in Santa Barbara, and Los Angeles was like a weird, distant backyard,” he began. “Our television stations were all out of LA so I became obsessed with, for example, commercials for Zachary All and Cal Worthington. Then we’d go to LA and it was so different from the picture-perfect neighborhoods of Santa Barbara; in the 1970s Los Angeles was pretty treeless, covered in billboards, blanketed in smog. Like a dying civilization, but with so many insane neon signs, so much bizarre architecture. The whole of the city was fantastical like Disneyland, albeit a giant, grimy, dystopic version of Disneyland.”

The career choice, however, was preordained. “My father was a historian and I follow in his footsteps,” Marsak explained. “While other parents took their kids to baseball games, I was being led through Florentine museums or the cathedrals of France. I would have been destined to become a historian no matter where I landed, but I’m very glad my home became Los Angeles.”

Taking up roots in LA, though, wasn’t always part of Marsak’s plans. He disclosed, “In the early 1990s, I was out in Wisconsin, going to graduate school and doing architectural history. But the lure of Southern California pulled me back, especially after I saw the ’92 riots on TV. I packed my things, and read Raymond Chandler and James Ellroy to acquaint myself with my new home, and moved to East Hollywood and began looking for ‘Old LA.’

“Sometime in the mid-90s, I was in a downtown bar talking up the old timers about lost Los Angeles and one of them said ‘you know there was a guy who took photos all around here back in the fifties, and he published a coupla books of them’ — referring of course to Arnold Hylen — and I immediately began combing the bookstores until I found Hylen’s 1976 Bunker Hill book, and his 1981 Los Angeles Before the Freeways.”

And reading those books became the impetus to discover the architectural history of his adopted home.

“I loved Hylen’s Freeways book, and used to drive around with it on my lap like a Thomas Guide of phantom Los Angeles,” said Marsak. “And because so few copies existed — Dawson’s Book Shop only printed 600 of them in 1981 — I made it my mission to reprint it.”

“But for all of Hylen’s groundbreaking research, as included in his indispensable essay, there were unanswered questions,” Marsak continued. “I wanted to flesh out the buildings with the addition of their architects and construction dates. Naturally, as well, I wanted the images to be larger, and clearer, and that would require being in possession of the original negatives, which I finally managed to purchase in 2016. Each negative strip had three images, so sometimes there were alternate angles or shots of something not in the book. I was thrilled to be able to include some of those never-before-seen captures.”

The original version of Hylen’s book contained 116 photos, and the expanded new edition of “Los Angeles Before the Freeways” has 143 images. Hylen began taking photographs downtown about 1950. The majority of his output occurred between 1955 and 1960, but there are images in the new book that date to as late as 1979, according to Marsak.

“This is not a book about buildings that were only lost to freeways,” Marsak clarified. “It also includes some structures that were demolished when the Hollywood Freeway made its easterly path through Fort Moore hill, and of course there are some images of the Harbor Freeway as it was constructed west of Bunker Hill. But most of the structures contained herein were lost to parking lots, or the expansion of the Civic Center. An accurate number for how many structures were razed because of freeway construction would be difficult to gauge, but a safe bet is about 1,000.”

The road to getting the book republished was long. Marsak recalled, “I established contact with Hylen’s family about 2006, and by the time I acquired rights and negatives, in 2016, I was already working on my Bunker Hill book for Angel City Press, so ‘Freeways’ took a back burner. I began writing the captions and scanning the ‘Freeways’ negatives in early 2022, which was about two years of work before I handed Angel City Press a completed manuscript in 2024.”

Marsak added, “I hope readers take away that there were first-rate domestic and commercial structures by top-flight architects in the 19th century. Naturally, the fact that the majority of the structures featured have been wiped away, I also hope causes readers to become active with preservation in their communities.”

Through this book, Marsak would also like us to have a better appreciation for the city.

“There’s more to Victorian LA than just the Queen Anne houses on Carroll Avenue or at Heritage Square — which are great, don’t get me wrong! — but we once had an incredible collection of Romanesque Revival, Italianate, and other styles blanketing the city in general, downtown in particular,” he emphasized.

Unfortunately, these magnificent edifices didn’t survive the wrecking ball and — but for the images in the book — no trace of their past existence remains.

“Very few people in postwar America were interested in architectural salvage from Victorian buildings,” Marsak lamented. “The Magic Castle, though, utilized parts of structures for its fanciful interior. And of course, most famously, two houses from Bunker Hill were moved to Montecito Heights as the first structures in the Heritage Square project. But they were sadly burned to the ground not long after their relocation.”

It’s a disgrace that the inspired works of eminent architects had to be sacrificed in the service of building something as pedestrian as a parking lot. Fortunately, we’re now repurposing the ruins of significant structures. Many interior decorators and designers are sourcing demolished materials to integrate into new construction to imbue character and a distinctive look. It’s one way to ensure that torn down buildings are given a second life.