In 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order that gave the U.S. army authority to compel 120,000 Japanese Americans believed to be security risks, to sell their homes and dispose of their possessions, and send them to ten concentration camps across the country.

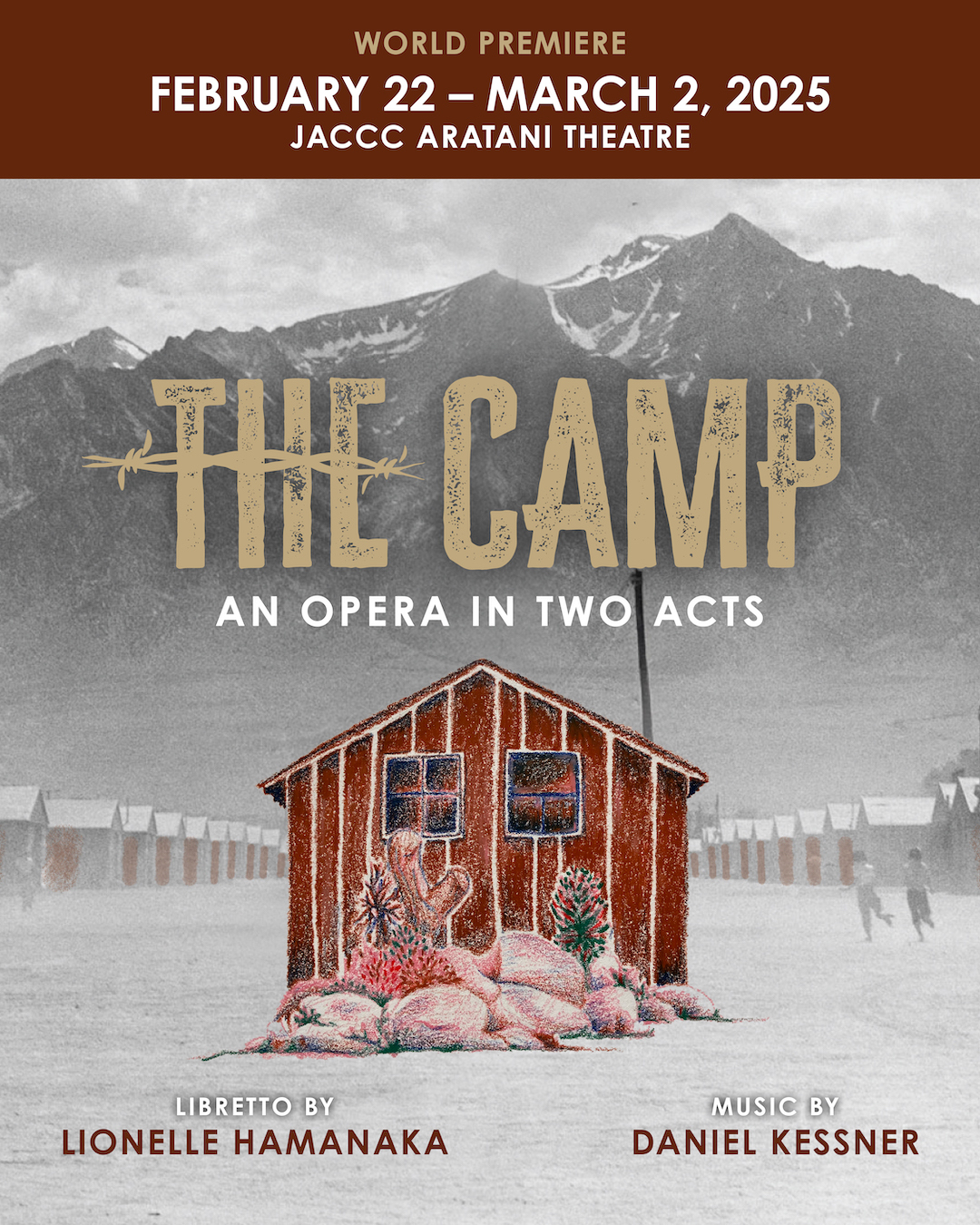

This internment of Japanese American men, women, and children — one of the darkest moments in U.S. history — is the topic of an opera called “The Camp.” It will make its world premiere on Feb. 22 with additional performances Feb. 23 and March 1 and 2 at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, which is within blocks of where 83 years ago families were loaded on buses in downtown Los Angeles and sent to the camps.

“The Camp” tells the moving story of the Shimono family, Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their suburban home in Southern California. After Mas, a fisherman and the head of the household, is arrested by the FBI on suspicion of espionage, the family is reunited in a desolate incarceration camp. As the family struggles to survive the emotional and physical toll of their wrongful imprisonment, this poignant, new opera illuminates the remarkable strength of familial bonds and the power of collective resistance in the face of injustice.

Presented in partnership with JACCC, “The Camp” is a collaboration between librettist Lionelle Hamanaka, composer Daniel Kessner and director Diana Wyenn. It features an intergenerational cast of eleven singers and a 22-member orchestra led by conductor Steven F. Hofer. The associate director is John Miasaki, joined by artistic consultant Anne Marie Ketchum de la Vega, scenic designer Yuri Okahana-Benson, lighting designer Pablo Santiago, costume designer Kathleen Qui and properties designer Brittany White to complete the creative staff.

The cast of eleven is headed by leading Los Angeles area vocalists — bass-baritone Roberto Perlas Gómez as Mas Shimono, mezzo-soprano Shu Tran as Haruko Shimono and soprano Tiffany Ho as Suzy Shimono. With Habin Kim as Rebecca Shimono, Patrick Tsoi-A-Sue as Nobu, Krishna Raman as the Commentator, FBI Agent and PFC Parker, Sarah Wang as Mrs. Hosaka, Steve Moritsugu as Tana, Dennis Rupp as Edwards and Reverend, Hisato Masuyama as Kenji and Jamie Sanderson as Taylor.

Speaking by phone just two weeks after the Palisades and Eaton fires, New York-based Lionelle Hamanaka precedes the interview by thoughtfully inquiring after my safety and well-being. She then likens the displacement the fires caused with what happened during World War II.

“I was looking at the population of the U.S. in 1945 compared to today,” Hamanaka begins. “In 2020 the U.S. population was 329 million, in 1945 it was 139 million — 120,00 Japanese Americans were displaced in 1942 because they were incarcerated and today about 200,000 California — specifically LA area — residents were evacuated because of the fires. A slightly higher percentage was displaced in 1942 than from the fire. Sixty percent of the residents lost their property or had to sell it in a week. I think the Japanese American population has in its collective memory a comparable tragedy to the one in California. It’s a horrible thing that it happened at all.”

Hamanaka, a sansei whose parents were incarcerated at the Arkansas Jerome War Relocation Center, wasn’t born yet during World War II. Her mother was in her late teens and had two kids while her father was about 20 years old and had graduated from Fresno State College when they met at the camp.

Like many people who endured the horrors of the Japanese American internment, her parents didn’t tell her or her siblings about their experience.

“I found out at 12 years old through my social studies teacher in class,” recalls Hamanaka. “Most Japanese Americans didn’t tell their kids because they didn’t want them to be burdened with a negative self-image.”

Learning about the camps changed Hamanaka’s entire life; she says she felt traumatized and never got over it.

I ask how she moved forward from that revelation and she replies, “I had a very different background. I think when we were little, my dad used to read us passages from classical literature, including the works of Shakespeare, E.E. Cummings, and other writers. Even though we didn’t understand all the words, we actually memorized a lot of poems and passages when we were 3 and 4 years old.”

“My father was an actor,” continues Hamanaka. “He was a very friendly guy and he used to have a salon in our apartment — as miserable as it was — on the Lower East Side. Because we lived where one-sixth of all Americans have passed through, it’s a very universal place. While it was segregated, my father’s circle wasn’t. He was friends with Isamu Yamaguchi and James Baldwin. Later he became friends with Mako, who was a very important actor. We had racially and sexually integrated salons at our house and I think that gave a healthy balance to the trauma that my parents had lived through.”

Hamanaka went to the Japanese American National Museum to get the records about the camp where her parents, half-brother and half-sister were imprisoned. “The Camp” integrates people’s experience from the various camps and the stories she had heard and read.

“My mother was imprisoned in Santa Anita Race Track, a local assembly point where she was in a horse stall for nine months, before she and others were transported to permanent camps. I referred to it in a dialogue in the opera,” Hamanaka discloses.

Prior to writing this opera, Hamanaka has had exposure to people’s work related to the concentration camps.

“I’ve read important works of literature written about the camps, including a book called ‘No-No Boy’ by John Okada,” she explains. “The topic has been covered in a musical on Broadway; I’ve seen George Takei’s ‘Allegiance,’ which was very good. An opera will appeal to a different audience. I think all segments of the population should be exposed to our history but nobody knows that history unless it’s available.”

According to Hamanaka, “The Camp” is a passion project for her and the others involved in it.

“I used to be a jazz singer and now I’m a playwright,” she says. “I think when you’re an artist you feel it’s necessary to express yourself. In the United States there’s no support for artists, therefore, there has to be a pretty compelling reason.”

“I think culture is a decisive factor in determining consciousness. Because as human beings, we have words and we are able to tell stories. I’m a minority woman and I live in 20th and 21st century. I’m Japanese American and we went through this experience — it’s a pivotal part of my life. Otherwise I wouldn’t have written these works that I have already done. We live in a segregated society and world; we’re divided nationally according to class and race. Within our country we’re segregated according to nationalities and generations, and so forth,” expounds Hamanaka.

“Culture is a way of people seeking understanding and education, of ending segregation, of having compassion and all of the virtues that are described in all religious work and oral literature from the beginning of time,” Hamanaka says further. “Therefore, it’s a need; it’s part of our identity as a species.

“Because when there’s no understanding, when there’s segregation, when there’s class, national, racial, and sexual antagonism, we wind up killing each other. It’s like the teachers used to say — use your words. I used to use music, now I’m using words. I was very lucky to meet Daniel Kessner on Facebook and do this project with such an acclaimed composer.”

Hamanaka concludes “I hope to some small extent I reflect the character of my people in that struggle and the struggle against racism in this country. Because we’re under attack right now and we need to have a big united front. If even one person or child who sees and hears the opera decides they’re going to do something and not be afraid, it is a victory.”