By Anna Maria Barry-Jester

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Lifesaving HIV treatments. Cures for hepatitis C. New tuberculosis regimens and a vaccine for RSV.

These and other major medical breakthroughs exist in large part thanks to a major division of the National Institutes of Health, the largest funder of biomedical research on the planet.

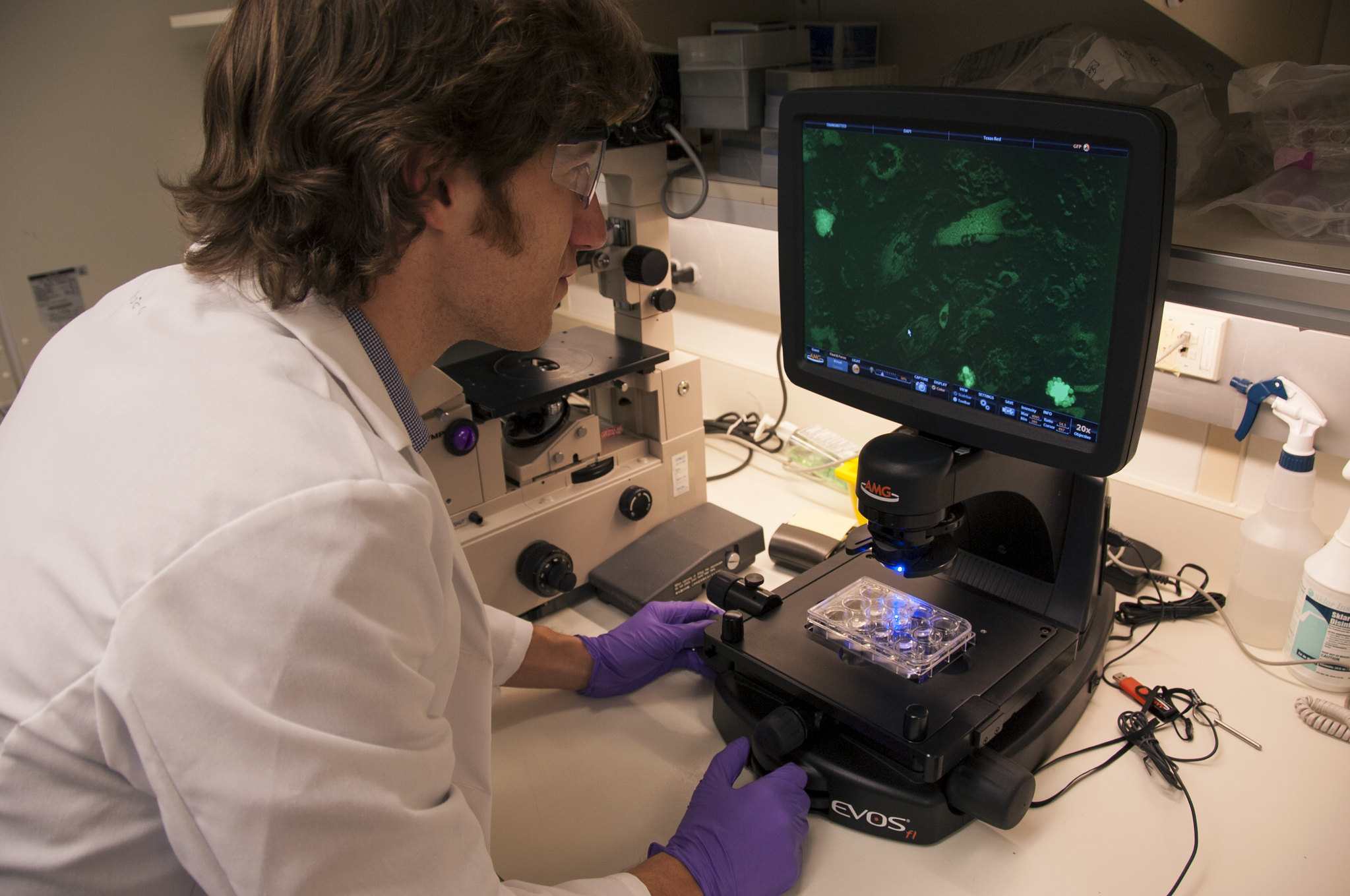

For decades, researchers with funding from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have labored quietly in red and blue states across the country, conducting experiments, developing treatments and running clinical trials. With its $6.5 billion budget, NIAID has played a vital role in discoveries that have kept the nation at the forefront of infectious disease research and saved millions of lives.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

NIAID helped lead the federal response, and its director, Dr. Anthony Fauci, drew fire amid school closures nationwide and recommendations to wear face masks. Lawmakers were outraged to learn that the agency had funded an institute in China that had engaged in controversial research bioengineering viruses, and questioned whether there was sufficient oversight. Republicans in Congress have led numerous hearings and investigations into NIAID’s work, flattened NIH’s budget and proposed a total overhaul of the agency.

More recently, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Trump’s nominee to run the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the NIH, has said he wants to fire and replace 600 of the agency’s 20,000 employees and shift research away from infectious diseases and vaccines, which are at the core of NIAID’s mission to understand, treat and prevent infectious, immunologic and allergic diseases. He has said that half of NIH’s budget should focus on “preventive, alternative and holistic approaches to health.” He has a particular interest in improving diets.

Even the most staunch defenders of NIH agree the agency could benefit from reforms. Some would like to see fewer institutes, while others believe there should be term limits for directors. There are important debates over whether to fund and how to oversee controversial research methods, and concerns about the way the agency has handledtransparency. Scientists inside and outside of the institute agree that work needs to be done to restore public trust in the agency.

But experts and patient advocates worry that an overhaul or dismantling of NIAID without a clear understanding of the critical work performed there could imperil not only the development of future lifesaving treatments but also the nation’s place at the helm of biomedical innovation.

“The importance of NIAID cannot be overstated,” said Greg Millett, vice president and director of public policy at amfAR, a nonprofit dedicated to AIDS research and advocacy. “The amount of expertise, the research, the breakthroughs that have come out of NIAID — It’s just incredible.”

To understand how NIAID works and what’s at stake with the new administration, ProPublica spoke with people who have worked for NIAID, received funding from it, or served on boards or panels that advise the institute.

Decisions, Decisions

The director of NIAID is appointed by the head of the NIH, who must be approved by the Senate. Directors have broad discretion to determine what research to fund and where to award grants, although traditionally those decisions are informed by recommendations from panels of outside experts.

Fauci led NIAID for nearly 40 years. He’d navigated controversy in the past, particularly in the early years of the HIV epidemic when community activists criticized him for initially excluding them from the research agenda. But in general until the pandemic, he enjoyed relatively solid bipartisan support for his work, which included a strong focus on vaccine research and development. After he retired in 2022, he was replaced by Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, an HIV researcher who was formerly the director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She has spent much of her time in the halls of Congress working to restore bipartisan support for the institution.

NIH directors typically span presidential administrations. But Donald Trump has nominated Dr. Jay Bhattacharya to lead NIH, and current director Dr. Monica Bertagnolli told staff this week that she would resign on Jan. 17. A Stanford professor, Bhattacharya has spent his career studying health policy issues like the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and the efficacy of U.S. funding for HIV treatments internationally. He also researched the NIH, concluding that while the agency funds a lot of innovative or novel research, it should do even more.

In March 2020, Bhattacharya co-authored an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal arguing that the death toll from the pandemic would likely be far lower than predicted and called for lockdown policies to be reevaluated. That October, he helped write a declaration that recommended lifting COVID-19 restrictions for those “at minimal risk of death” until herd immunity could be reached. In an interview with the libertarian magazine Reason in June, he said he believes the COVID-19 epidemic most likely originated from a lab accident in China and that he can’t see Trump’s Operation Warp Speed, which led to the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines at unprecedented speed, as a total success because it was part of the same research agenda.

Bhattacharya declined an interview request from ProPublica about his priorities for the agency. A recent Wall Street Journal article said he is considering how to link “academic freedom” on college campuses to NIH grants, though it’s not clear how he would measure that or implement such a change. He’s also raised the idea of term limits for directors and said the pandemic “was just a disaster for American science and public health policy,” which is now in desperate need of reform.

Where the Money Goes

Grants from NIAID flow to nearly every state and more than half of the congressional districts across the country, supporting thousands of jobs nationwide. Last year, nearly $5 billion of NIAID’s $6.5 billion budget went to U.S. organizations outside the institute, according to a ProPublica analysis of NIH’s RePORT, an online database of its expenditures.

In 2024, Duke University in North Carolina and Washington University in Missouri were NIAID’s largest grantees, receiving more than $190 and $173 million, respectively, to study, among other things, HIV, West Nile vaccines and biodefense.

Over the past five years, $10.6 billion, or about 40% of NIAID’s budget to external U.S. institutions, went to states that voted for Trump in the 2024 presidential election, the analysis found. Research suggests that every dollar spent by NIH generates from $2.50 to $8 in economic activity.

That money is key to advancing medicine as well as careers in science. Most students and postdoctoral researchers rely on the funding and prestige of NIH grants to launch into the profession.

New Drugs and Global Influence

The NIH pays for most of the basic research globally into new drugs. The private sector relies on this public funding; researchers at Bentley University found that NIH money was behind every new pharmaceutical approved from 2010 through 2019.

That includes therapies for kids with RSV, COVID-19 vaccines and Ebola treatments, all of which have key patents based on NIAID-funded research.

Research from NIAID has also improved treatment for chronic diseases. New understandings of inflammation from NIAID-funded research has led to cutting-edge research into cures for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and a growing body of evidence shows how viruses can have long-term impacts, from multiple sclerosis to long COVID. When private companies turn that research into blockbuster drugs, the public benefits from new treatments, as well as jobs and economic growth.

The weight of NIAID’s funding also allows it to play quieter roles that have been essential to advancing science and the United States’ role in biomedicine, several people said.

The institute brings together scientists who are normally competitors to share findings and tackle big research questions. Having that neutral space is essential to pushing knowledge forward and ultimately spurring breakthroughs, said Matthew Rose of the Human Rights Campaign, who has served on multiple NIH advisory boards. “Academic bodies are very competitive with one another. Having NIH pull the grantees together is helpful to make sure they talk to one another and share research.”

NIAID also funds researchers internationally, ensuring the U.S. continues to have an influential voice in global conversations about biosecurity.

NIH has also been working to improve representation in clinical trials. Straight, white men are still overrepresented in clinical research, which has led to missed diagnoses for women and all people of color, as well as those in the LGBTQ+ community. Rose pointed to a long history of missing signs of heart conditions in women as an example. “These are the type of things commercial companies don’t care about,” he said, noting that NIH helps to set the agenda on these issues.

Nancy Sullivan, a former senior investigator at NIAID, said that NIAID’s power is its ability to invest in a broad understanding of human health. “It’s the basic research that allows us to develop treatments,” she said. “You never know which part of fundamental research is going to be the lynchpin for curing a disease or defining a disease so you know how to treat it,” she said.

Sullivan should know: It was her work at NIAID that led four years ago to the first approved treatment for Ebola.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox. Republished with Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).