In the final days leading up to the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, U.S. diplomats organized the massive evacuation of American and South Vietnamese citizens in an operation called Operation Frequent Wind. The capture of Saigon by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, which marked the end of the Vietnam War, was a humiliating failure of American foreign policy in Southeast Asia.

Elizabeth Ai, a Chinese-Vietnamese-American writer, filmmaker, and producer who was born and raised in Alhambra, in the western San Gabriel Valley, documents the stories of the people who were transplanted here in the aftermath of the Vietnam war.

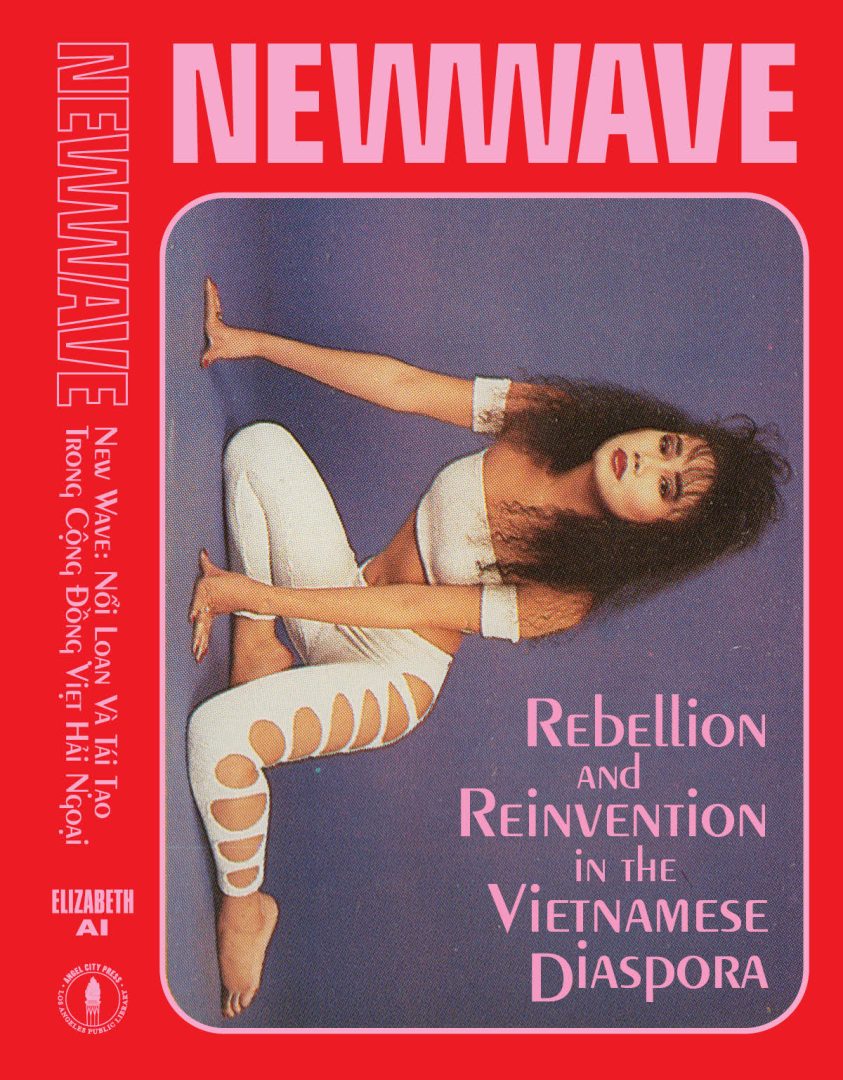

Ai’s film documentary “New Wave” and companion book “New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora” shine a light on the music that saved the 1.5 generation — refugees who were born in Vietnam but were raised in the United States. Many of these young people in Southern California found a new life and a new identity in New Wave music, a type of Euro Disco that became enormously popular in this community.

The idea for the film was conceived in Ai’s head in 2018 when she was pregnant with her daughter. She reveals that it started out as a documentary focused on the Vietnamese as a way to leave something for her daughter. She was trying to save the memories of this community before they disappeared but, in time, it all blurred into her own family history. As people shared their stories, she discovered how much they mirrored hers.

“New Wave,” the film, begins with a news clip showing the arrival of close to 160,00 Indo-Chinese refugees who first settled in Camp Pendleton and other settlements. It centers on the lived experience of Ai’s two main interviewees Ian Nguyen and Lynda Trang Đài — prominent artists of the music genre when the young refugees came of age in the 1980s — and her own.

Ian Nguyen, who goes by the professional name DJ BPM, is one of the remaining New Wave artists. He describes what it was like to live in a new country; they shared a house with four different families. It was through one of the teenage boys that he discovered New Wave music. With its steady disco beat, electronic drums and synthesizer, it seemed ahead of its time.

Several record stores in Chinatown started carrying cassette tapes and vinyl records of the music which sounds like today’s Depeche Mode. They called it New Wave and the name stuck; in the 1980s it was played at all Vietnamese supermarkets and restaurants.

Nguyen started deejaying in LA, Orange County and San Diego; he has been a New Wave DJ and concert producer for almost 40 years.

After his daughter was born, Nguyen decided to try to rebuild a relationship with his father. He went to visit his dad in the nursing home and, at his father’s request, he drove around to show him the houses he used to live in. It turned out to be a very emotional reunion because it was the first time he hugged his father.

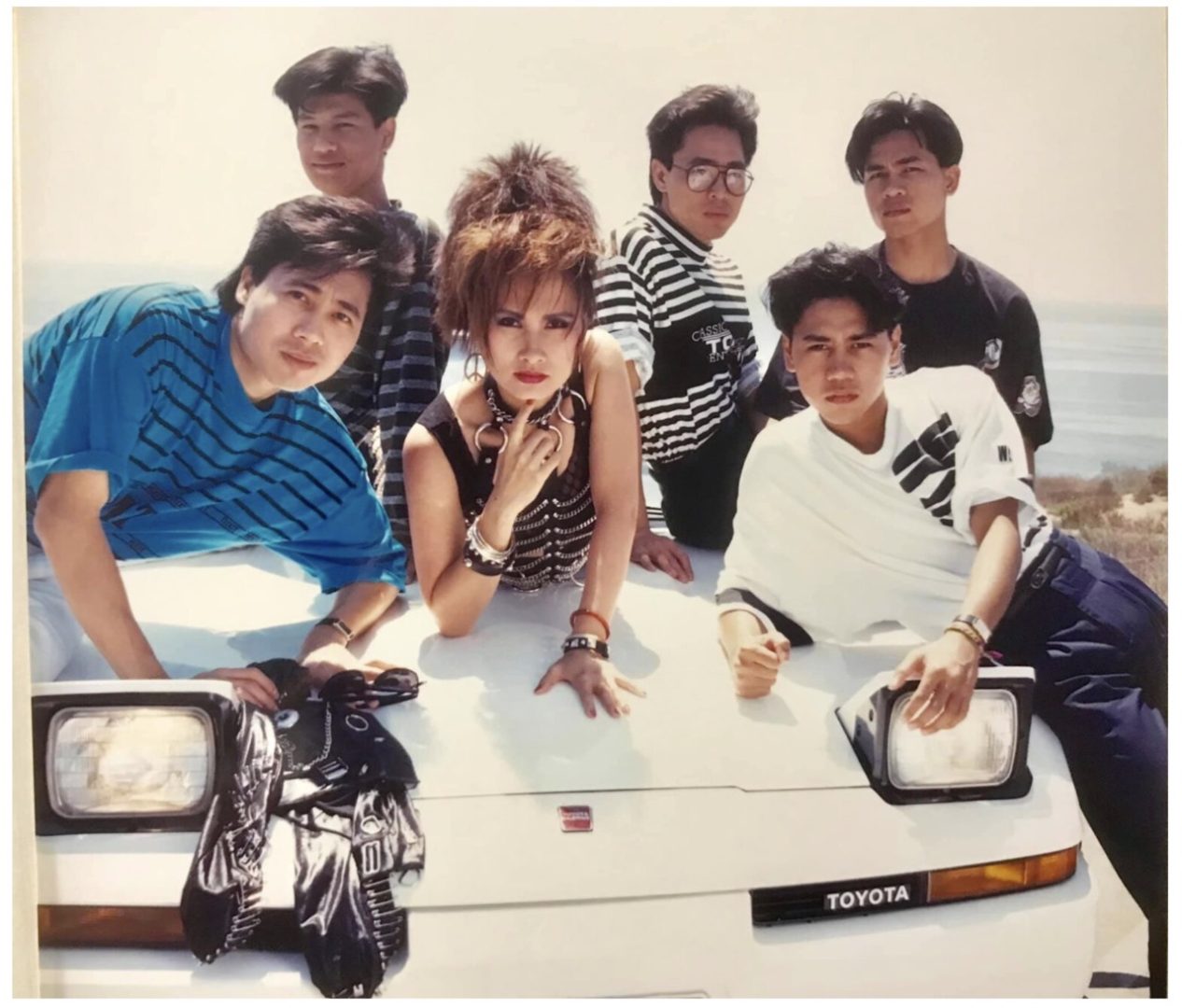

New Wave singer Lynda Trang Đài, is called the Vietnamese Madonna. When she arrived here, she says she saw white, black and Hispanic singers, but no Vietnamese artists — and she dreamed of being the first. She started out singing at community events.

It was when she was a high school senior that Đài began singing professionally on weekends at night clubs. During one of her weekend gigs she was discovered by a Vietnamese TV producer of a show called “Paris by Night,” a variety program that catered to the Vietnamese in Paris. For some, it was the only way to see other Vietnamese people; for another generation, it was a way to dream about their homeland.

Her show debuted on the same week as her high school graduation and “Give me your Love Tonight” was the song that launched her career. Young people loved Đài’s revolutionary music and the Lyndaholics became her loyal followers.

Đài became internationally famous and performed in Australia, New Caledonia, Moscow, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Norway, Finland, England, Germany, Italy and all over Asia. After several years of collaboration, the producers of Paris by Night put on Đài’s final performance. It was the end of her TV career.

Shortly after that, Đài had a baby. To earn a living she opened a sandwich shop, which she ran while still touring with her husband Tommy who was also a singer. Because they were gone so much they didn’t spend a lot of time with their son, who grew up resenting their career and employment choices.

In the film, Ai discloses that Đài reminds her of her mom, Lan. She was very good at what she did and she broke the rules about what it meant to be a traditional Vietnamese woman. Behind her stage persona was someone who took care of her family and provided for them.

Like Đài, Lan was the sole breadwinner for their entire family. She was pushed by her own parents to take care of her 12 siblings.

Lan came to America but ended up divorcing her husband and becoming a single mom. She worked day and night so she could pay for the mortgage and the cars, and send money to relatives back in Vietnam.

And when these relatives came here, Lan helped them start new lives. She put them through school and bought them cars; she purchased a house for her grandparents and even funded their gambling hobby.

Because her mom was moving from one nail salon to another trying to build an empire, Ai was practically raised by surrogate parents — her Aunt Myra, her mother’s sister, and a rebellious uncle. She and her brother lived with their grandparents. They saw very little of their mom and they eventually became estranged.

Ten years after Ai last saw Lan, she reunited with her mom, who lives in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. She took her little daughter there to meet her grandmother for the first time.

The audience can feel the tension between Ai and her mom as she expresses how she felt abandoned as a young child. It’s no longer a film about the Vietnamese people and how they coped in their new environment, but of the filmmaker’s personal journey and her courageous decision to confront her own buried trauma.

“New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora,” the film’s companion book, contains essays by Elizabeth Ai, Thúy Đinh, Thúy Võ Đặng, Thao Ha, Lan Duong, Eric Nguyen, Carolyn Huynh, Julia Huỳnh, Thuy Tran, Paul Quốc Trần and Trace Le. It is a story of joy and youthful defiance, showing how young Vietnamese refugees reinvented themselves in the West through music, fashion and community.

Speaking by phone, Ai discusses the film and the book, and people’s reaction to the documentary.

“Featuring Lynda Trang Đài was a no brainer,” Ai declares. “She’s the Vietnamese Madonna so I had to have her in the film. DJ BPM was someone I met randomly at a night club where my team and I went to for revival parties. He was a big fan of the New Wave music, not necessarily Lynda but of the Euro-disco artists. He used to deejay music at garage parties. They had to import this music in and he was one of the original people on the scene listening to the music. He collected these New Wave vinyl records when he was a teenager until he was in his 50s.”

Ai mentions in the film that her life changed when she had a baby and that made the big difference on how the documentary evolved.

“Beyond the Asian American community, I really wanted to touch on the theme of parent and child relationship,” Ai says. “I don’t know if everyone wants to be a parent, but each one of us is someone’s child and we understand the friction and tension. You don’t have to be an immigrant or a refugee, or a child of a refugee, to understand what it feels like to not belong sometimes. But I do feel that the barriers, the challenges, and the obstacles become greater as a refugee or an immigrant — as somebody who is of two different worlds and cultures.”

“I feel that as a theme, the relationship between a child and a parent is universal,” Ai continues. “We’re fighting for our identities and sometimes our parents don’t understand or have their own obligations and circumstances. I think, for me, having had the privilege to be a parent on my own terms really made it even more intense the need to be able to share a part of my story with my daughter.”

Ai adds, “A lot of people thought I would be going into Vietnam war stories. But for me it was more important to talk about that time when my uncle and aunties — the people who raised me — were the ones navigating this space with so much complexity and struggle. We always look at the adults who are learning English at night and working three different jobs. At the same time, it’s very challenging to be a young person in this world trying to figure out who you are.”

The pandemic happened in the middle of filming so Ai and her team largely paused production throughout 2020 and 2021, prompting a start to their Instagram page to crowdsource archival material. It was also how the companion book came about.

“I got so many archives from the community with our social media, on Instagram, and our crowd sourcing that I felt it was necessary to share some of the documents that didn’t go into the film in this different medium,” Ai says. “So that if people didn’t see the film, they could find the material in a different way. In the same token, it’s something that I felt was necessary because we don’t see these archives of us being saved by western, White American media. They don’t preserve our history.”

The authors who contributed essays in the book wrote about belonging.

“The sense of wanting to belong and having their own world that they can build,” Ai explains. “Between all the other essays and my contributions, it really was to show that for so long we have been kept out of the narrative that we see on TV, or in film, or in books.”

Ai says further, “I really believe that both the film and the book are acts of community preservation and community film- and book-making. It’s really important to me to acknowledge all the people who contributed — even the act of taking a photograph and saving it — so that we could share it in this way.”

While Ai’s family — her maternal grandparents, parents and her mom’s siblings — were refugees, she was not. And she thinks it’s because of it, not in spite of it, that she’s more involved in her ethnic community much more than immigrants are.

“Our whole life, we had the obligation to assimilate,” reasons Ai. “When we become adults we ask ourselves why we haven’t been more immersed in this world. It’s imperative that we realize all of this white-washing of culture. I’m in my 40s and as a teenager all I ever saw on magazine covers were white women; it was the most radical thing when you finally saw a black woman on the cover of a magazine or in a film.

“But it’s still rare to see an Asian person in the media, so now we get to change that narrative,” Ai adds. “It’s beautiful to see this reclamation happening among Asian Americans in the global diaspora. Even though we were displaced by American wars happening in our country, we could still reclaim our heritage. I think we all still want to be very much connected to our ancestry; this is our cultural inheritance. I see a lot of young people in their 20s doing it and I’m as proud of them as much as I’m inspired by them.”

Those who’ve seen the film are not only asking questions, but also sharing their family dynamics as well as the challenges they have to overcome.

“That’s what the problem is with this model minority myth,” Ai observes. “We’re all perceived as crazy rich Asians who do great in school. But that’s not true across all our diasporas; that’s not true for all cultures, not Chinese, or Japanese, or Korean, or Filipino. Everybody struggles and it’s very harmful to have these stereotypes because that becomes the expectation. Then people believe that you don’t need help or that you don’t have problems. The misconception that ripples through the community is that we’re all doctors and lawyers.”

“It’s important to have these conversations — with each other, with our parents, with our children. And as artists, to tell the stories and to say that we worked hard and we struggled, and there’s pain in the community even when we appear to be successful. I think that to have humanity is to see the full scope of what it is for each one of us,” Ai emphasizes.

“New Wave” had its world premiere in New York at the Tribeca Film Festival in June where it won a Special Jury Award for best new documentary director. It will be playing in over 20 film festivals before the end of the year. Since Tribeca the film has been shown in California — in LA, Orange County, and San Diego — and all over the United States. It has likewise been screened in Germany, Poland, and other countries.

A majority of the audience at the Vietnamese Film Festival were Vietnamese but the people who have attended the screening and have come out to support it have not been exclusively Asian Americans.

It’s heartening that the Vietnamese community and, by extension, Southeast Asians are having this opportunity to be seen and heard as “New Wave” tours the country and the globe. It’s one more step taken on the long road towards belonging and inclusion.