On Nov. 5, tens of millions of Americans will head to the ballot box to vote in one of the most consequential presidential elections in recent history. With so much on the line, anxious election-watchers naturally want clarity on the outcome.

But can any poll, no matter how precise, offer a reliable glimpse into where the cards will fall on Election Day? The answer is complicated, especially given that this year’s election is particularly tricky to forecast.

For starters, there’s no clear frontrunner. Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump are in a dead heat, according to polls. Predictions based on close numbers are precarious; a last-minute surprise could tilt the election one way or the other.

What’s more, trust in institutions is low. Just 46% of Americans in 2024 say they trust politicians “a great deal” or “a fair amount,” according to Gallup surveys, down from 68% in 1972. Trust in the media has dropped even more precipitously over the same period, from 68% to 31%.

Many voters rightfully look at predictions with a jaundiced eye after the 2016 election, which serves as a cautionary tale: Surveys erroneously suggested that Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton was headed for a solid victory, and then went on to lose the race by a narrow margin.

Polls simply do not carry much weight among Americans, and many question their legitimacy. Yet there’s palpable tension between the skepticism around polling and the desire for crystal ball clarity.

So, where do we go from here?

Stacker looked at news reports and academic research to see what the polls suggest about the 2024 election and explain why outcomes can be so difficult to pin down.

The polls are tightening

The U.S. is at an inflection point, having emerged from a difficult economic period after weathering a pandemic and coping with the highest levels of inflation in years. In addition to helping the nation recover from economic turbulence, the next president will inherit multiple wars and possibly pick a new Supreme Court justice. Whether founded or not, dire headlines about the end of democracy make the stakes of this election impossibly high — intensifying the desire for clarity among the electorate.

Amid this heightened tension, the election itself has taken an unusual course. Neither party held competitive primaries, and the candidates from both major parties were well known.

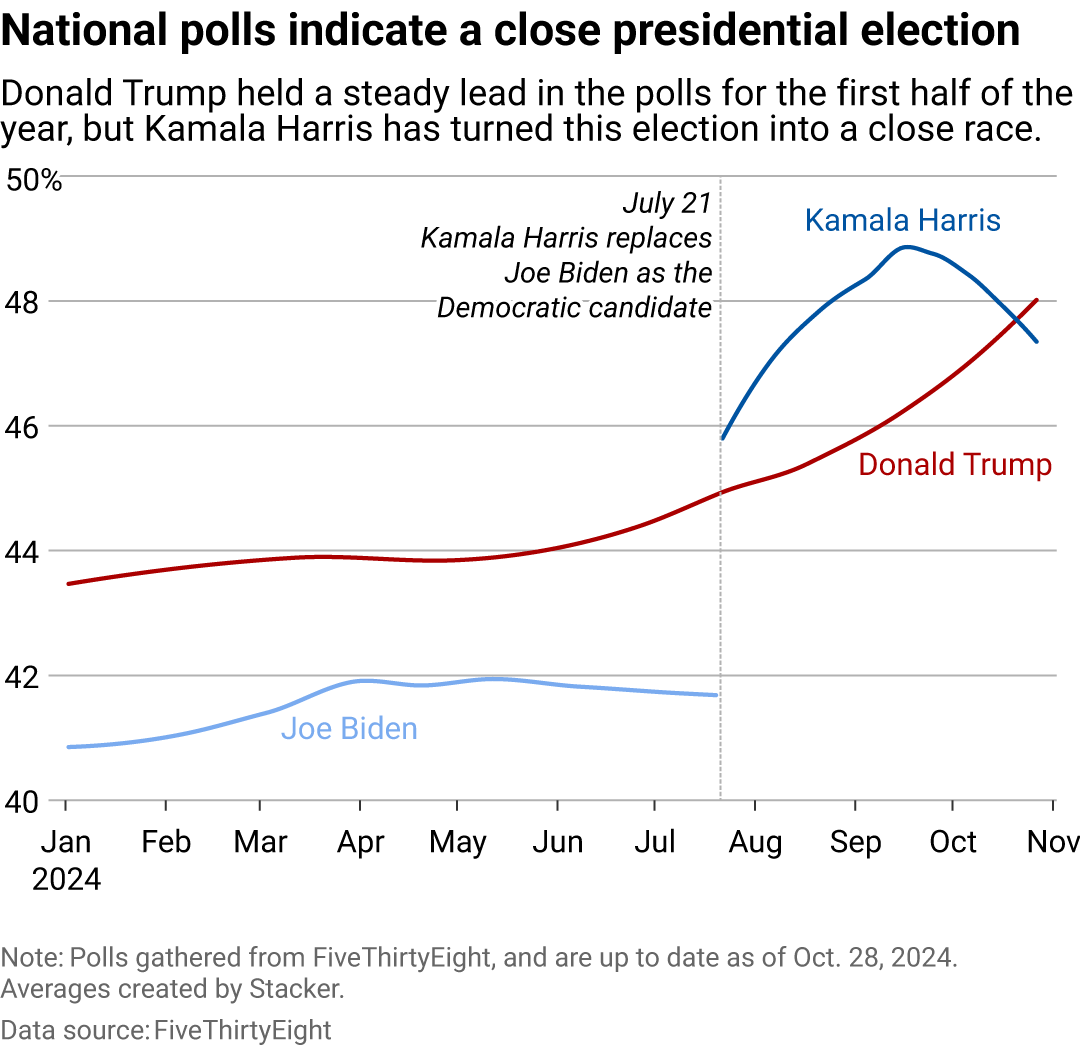

For the entirety of this year, Donald Trump led Joe Biden in the polls. The two candidates on June 27 held their only debate of the year. Biden performed poorly throughout the debate, leading many prominent Democrats to call for him to withdraw his candidacy over age-related concerns. Weeks later, Trump narrowly survived an assassination attempt at a rally in Pennsylvania.

These unusual events might have caused a shift in the polls — but they didn’t.

The polls only budged on July 21 when Biden announced he would not seek reelection. The move paved the way for sitting Vice President Kamala Harris to become the nominee. This candidate switch revitalized Democrats: Harris performed far better in the polls than Biden did.

As of Oct. 28, national polls show Harris and Trump in a dead heat to win the popular vote. This is not comforting to either political party. Headlines declaring the candidates are in a “deadlocked race” and in “the closest race in 60 years” do little to quell voters’ anxiety.

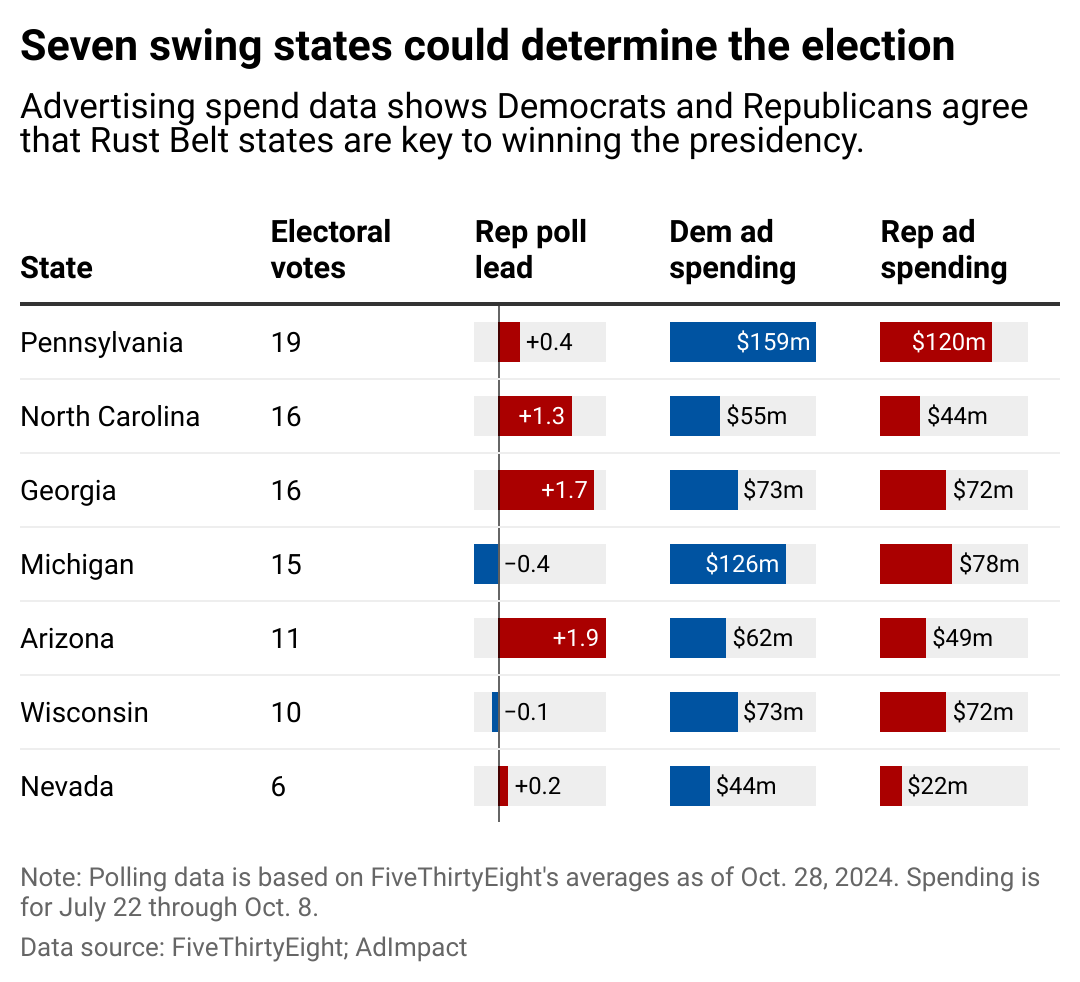

The electoral college ultimately decides the presidency, making forecasting the race especially challenging. National polling can show one candidate winning, but whoever wins enough swing ultimately becomes president. The race could even be decided by a handful of small communities in swing states, making this nail-biter of an election even more tense. In layman’s terms, no one knows what will happen.

In the last two elections, the Republicans held roughly a 3-point “electoral advantage,” meaning they could lose the popular vote by 3 points and still win the presidency. A New York Times analysis published Sept. 25 suggests, based on current polling, the Republican electoral advantage could be down to just 0.7 points this year. This means any poll that shows a tie on the national level implies an electoral loss for the Democrats.

Accurate polling is challenging

Polling is as much an art as it is science. To put together a single poll, researchers start by interviewing a few hundred to a few thousand people, asking questions about their demographic characteristics, political affiliations, and preferences for the upcoming election.

Pollsters then analyze the data and adjust, or weight, the responses to make them representative of the electorate as a whole. For instance, if only 20% of survey respondents are between 18 and 30, but pollsters anticipate that 30% of voters will be aged 18 to 30, they need to adjust the data accordingly.

They also need to factor in the poll’s margin of error, which measures how uncertain a poll’s results are based on its sample size. For instance, a Reuters/Ipsos poll released on Oct. 22 showed 46% of voters for Kamala Harris, with a 3% margin of error. This means pollsters believe the true number of people who will vote for Harris ranges between 43% and 49% — about 95% of the time.

If Harris leads Trump by 1 percentage point, that 3-point margin of error can make or break the race.

However, the margin of error only accounts for a particular kind of statistical uncertainty. Pollsters face other challenges, including uncertainty around turnout and declining response rates. There could also be “shy voters” who make false statements about who they plan to vote for. These factors add further uncertainty to polling numbers.

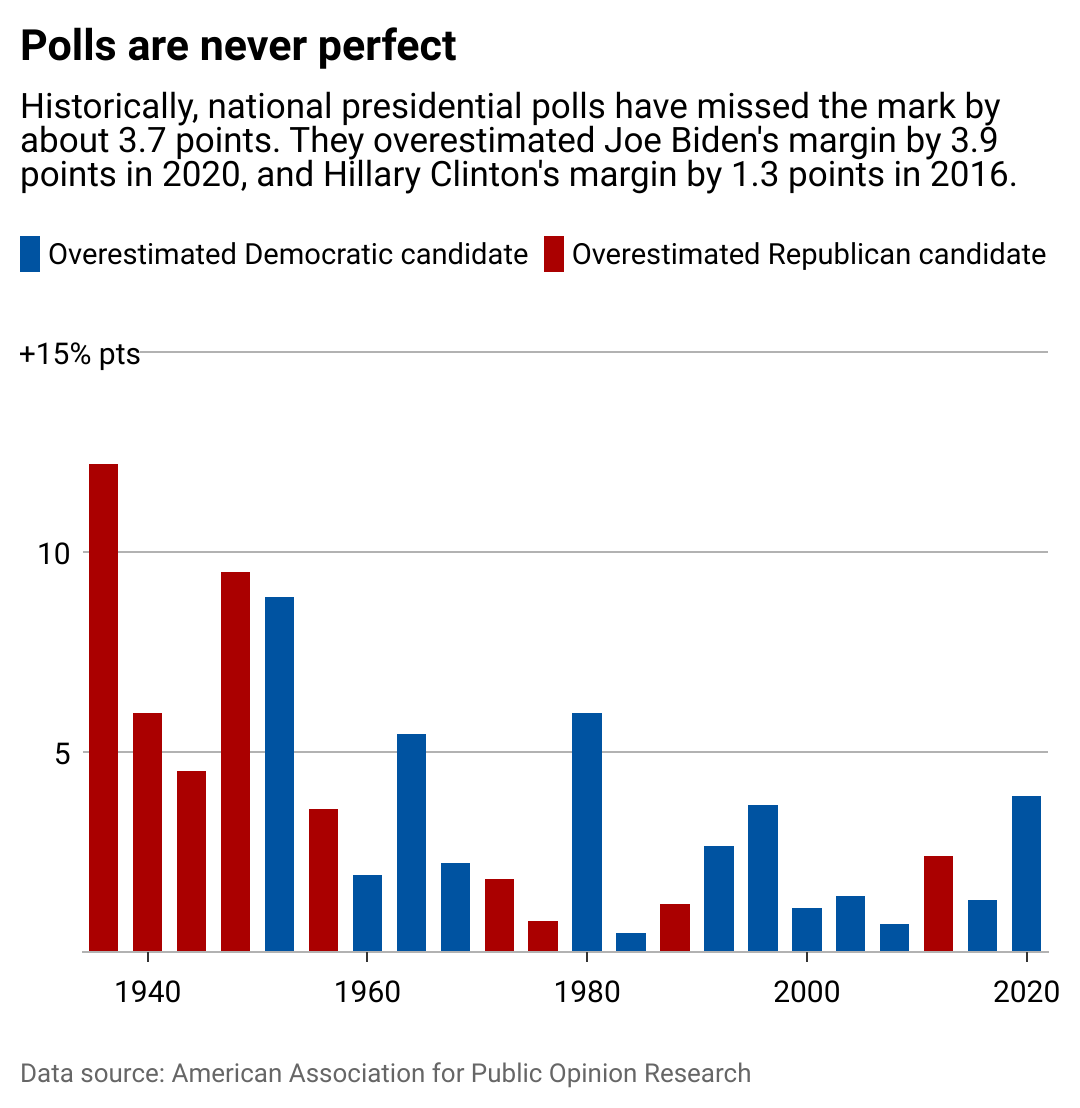

A more comprehensive way to understand how much polls can err is to look at the track record. According to the American Association for Public Opinion Research, presidential polls have historically been off by an average of 3.7 points since 1936.

This means forecasts based on tight polls could incorrectly guess the winner of the popular vote.

The two parties are zeroing in on the Rust Belt

Polls did a better job estimating the popular vote in 2016 than in 2020. Polls took more heat in 2016 because they misfired at the state level, overestimating Clinton’s advantage by around 5 points in three crucial swing states: Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

Data from FiveThirtyEight showed Clinton up roughly 4 points in the polls in these key Rust Belt states leading into the election. In reality, Clinton lost all three states by fewer than 78,000 votes.

Those same three states are poised to be pivotal in the 2024 race. Both candidates are focusing their campaign efforts in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania and pouring tens of millions of dollars into advertising there. Current polls show Harris and Trump within 1 point of each other in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

Given that state-level polls have missed by an average of around 5 points in the past 20 years, no one can confidently say who will prevail in those states. The other four key swing states that the two candidates have zeroed in on — Nevada, North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona — are also well within this 5-point margin.

Demographic shifts are afoot

Pollsters slice data in all kinds of ways to understand how people are voting. One way they do so is through cross-tabulations, or crosstabs, which compare the impact of one variable with another. This allows them to identify voting patterns across demographic variables like race, age, and gender.

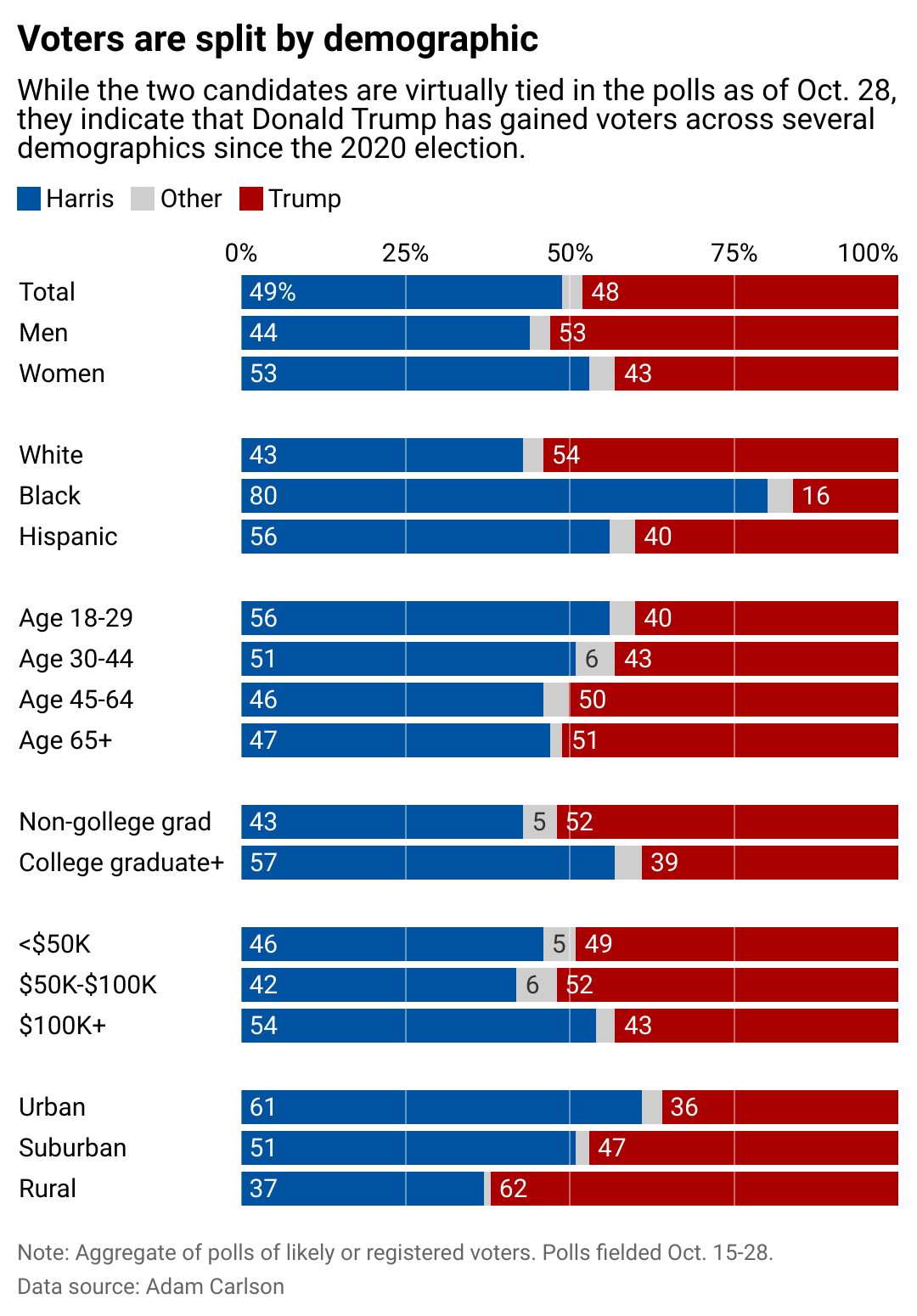

Adam Carlson, a former Democratic pollster, has compiled crosstabs from a wide variety of general election polls, which look at how particular demographics plan to vote. A typical general election poll of roughly 1,000 respondents might have only a few hundred — or even just a few dozen — respondents from a narrow slice of the population. But by highlighting that small cohort using crosstabs, pollsters can identify trends and patterns among a particular group.

If, for instance, you wanted to know how rural voters were leaning in the election, looking at any one poll would likely give you unreliable information. However, aggregating crosstabs on rural voters across multiple polls could, in theory, yield more accurate numbers.

Current polling indicates that most demographics are voting similarly to how they did in past elections. In general, women, college-educated voters, people living in urban areas, Black and Hispanic people and younger people tend to favor the Democrats, while men, voters without bachelor’s degrees, people living in rural areas, white people and older voters tend to prefer Republicans.

However, the votes of many young Latino voters are still up for grabs. Latinos are the fastest-growing demographic in swing states, and with many young Latino voters identifying as independent, this cohort may still be swayed by either candidate’s messaging. It’s yet another example of why forecasting this election is so challenging.

Survey data suggests that there have been a few shifts in how people are voting compared with the previous election, including notably Black and Hispanic voters. In 2020, Biden was estimated to win the Black and Hispanic votes by 83 and 24 points, respectively. Current data suggests that Kamala Harris will win amongst these demographics by just 65 and 20 points.

There also appears to be movement among college-educated voters. In 2020, Biden led among voters with bachelor’s degrees by 14 points, compared with Harris’ current lead of just 5 points.

If these forecasts hold up at the ballot box, they would constitute a major realignment of American politics. But if they are wrong, they could indicate that this year’s polls are especially unreliable.

Elections are increasingly coming down to the wire

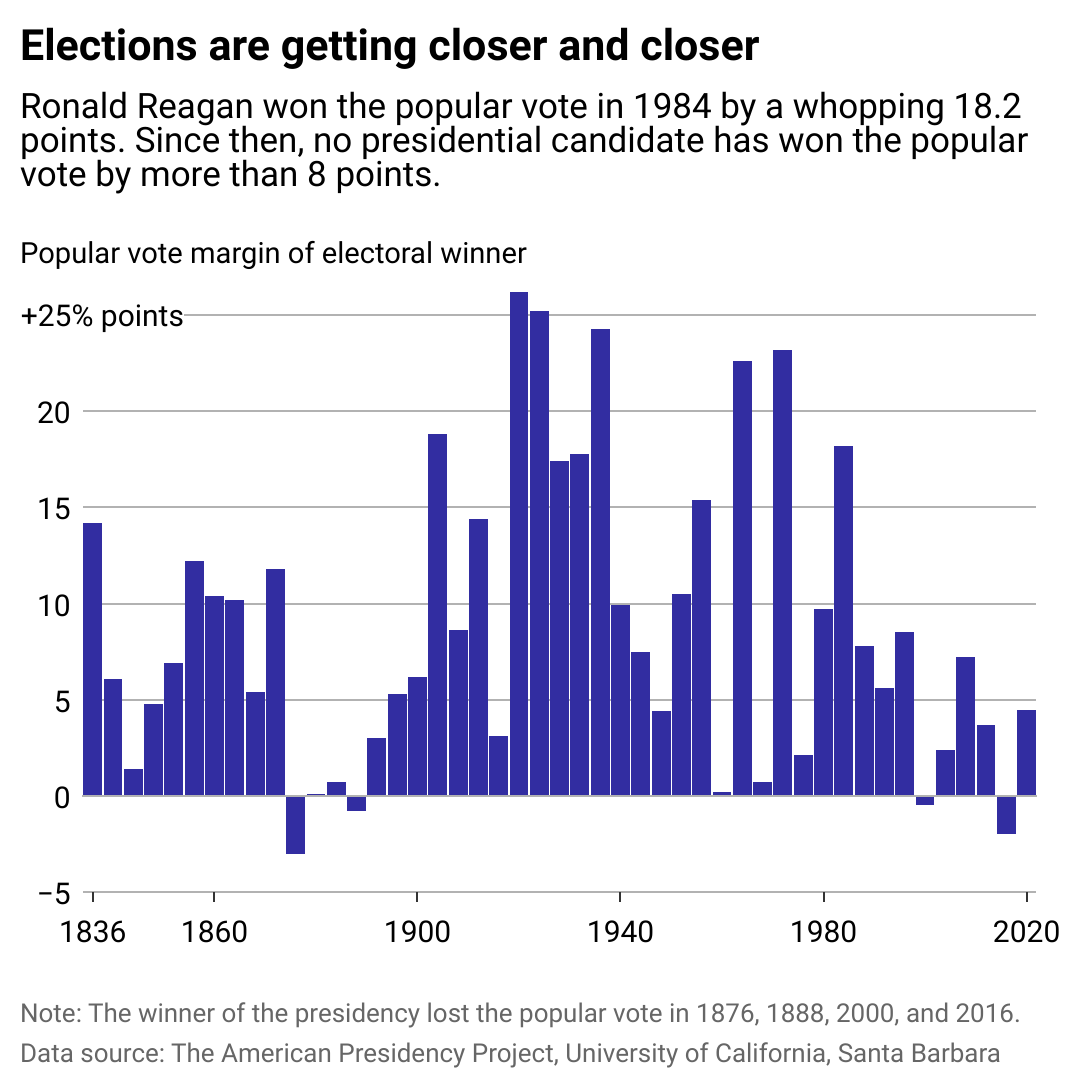

Understanding polls requires awareness of one of the prevailing trends in American politics: Elections are becoming closer and closer. It used to be expected for presidential candidates to beat their rivals by double digits in the popular vote. Ronald Reagan, for example, won reelection in 1984 with an 18-point lead over Walter Mondale in the popular vote.

But over the past four decades, margins have tightened, with no winning candidate taking the White House by more than an 8-point margin. Biden won the presidency in 2020 with a 4.5-point lead, while Trump won in 2016 despite losing the popular vote by 2 points.

Increased partisanship could explain some of these results. Americans routinely say the economy is the most important issue, but people’s perceptions of how well the economy is doing now heavily depend on whether their preferred party is in office.

At the start of 2020, when Donald Trump was still president, Pew found that 81% of Republicans thought the economy was doing well compared with just 39% of Democrats. More recent polls from this past September show that only 10% of Republicans feel good about the economy versus 41% of Democrats. No such partisan divide in perceptions existed in the 1990s.

Several factors contribute to this increased polarization, including but not limited to the 24/7 news cycle, a more partisan press, the rise of social media, and economic uncertainty. Regardless of its cause, a divided electorate will care more about their side winning than policy debates. While this might suggest an electorate with strong opposing preferences, a 50/50 election is actually precisely what social science would predict in a two-party race.

Current forecasts from the betting markets and election analysts show the race will be close to a 50/50 bet, with Trump generally having a slight lead, depending on the source. No matter what happens in the coming days, one thing is clear: No one — not even professional forecasters — knows exactly how the election will pan out.

Written by Wade Zhou. Story editing by Alizah Salario and Elena Cox. Additional editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

The article was copy edited from its original version.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.