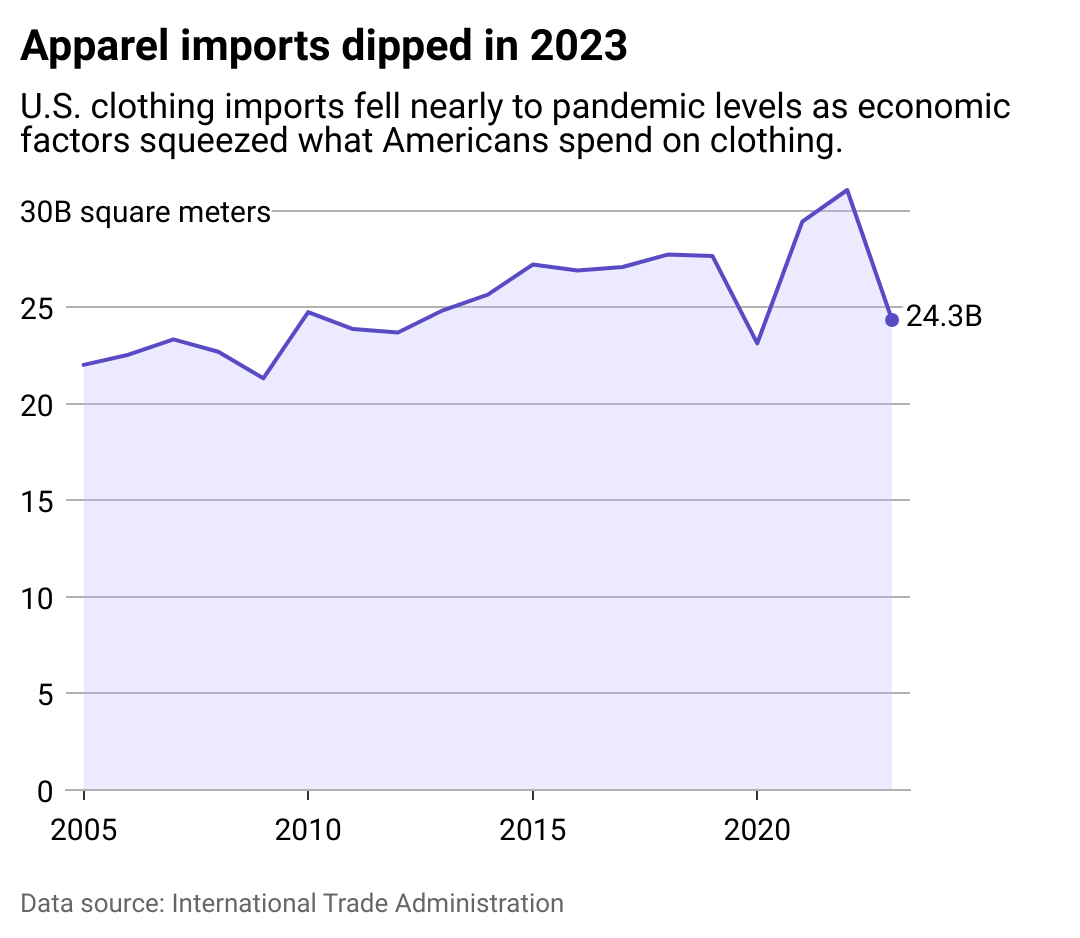

It’s no secret that fast fashion imports from international brands like H&M, Zara and Shein have come to dominate Americans’ wardrobes. The U.S. imported more than $24 billion of apparel in 2023, and consumer demand shows no sign of slowing.

Fast fashion came to prominence in the early 1990s, though the concept had been around since the ’70s. Until about half a century ago, most Americans purchased textiles and clothing made in the U.S. of A. Since the Industrial Revolution, Americans enjoyed wide availability of mass-produced textiles, but only during two cycles: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter, the traditional seasons for new fashion releases.

Later, as trade relations warmed between China and America in the 1970s, demand skyrocketed for luxurious Chinese clothes such as embroidered silks. Combined with the relatively new technology of containerized shipping, which allowed companies to ship massive quantities at low costs, savvy business owners became wise to a new possibility: importing garments made cheaply in other countries and selling them at a profit.

But it wasn’t until the early ’90s, when Zara’s first brick-and-mortar store in the U.S. took off, that fast fashion gained ground. The fast-fashion business model depends on cheap, rapid cycles of production that allow retailers to push out batches of clothing while styles are still at the peak of popularity. This means consumers can snap up garments inspired by the hottest runway trends — known as “dupes” — for a small fraction of the couture price.

Over the next decades, as more international brands came stateside and e-commerce took off, clothing production was further expedited, making fast fashion even faster. Today, it’s hard to avoid buying clothing manufactured outside the U.S. — the days of waiting for seasonal clothing collections are long gone. Brands like Zara and Forever 21 now produce an estimated 52 micro-seasons every year. Social media has continued to speed up trend cycles, increasing demand for the latest and greatest looks.

However, the accessibility of fast fashion comes at a cost. The RealReal analyzed data from the International Trade Administration to explore how clothing imports have shifted over the past 20 years — and what it means for both people and the planet.

The data shows imports in terms of both U.S. dollars and quantity, focusing specifically on clothing instead of accessories and shoes. Quantity values are in square meter equivalents and do not represent individual items imported into the U.S.

The growth of fast fashion fueled environmental issues

Fast fashion’s meteoric rise is apparent in retail giants like Shein and Uniqlo, which both saw more than 20% revenue growth between 2022 and 2023 alone. But, as the industry grows, the human and environmental toll has also increased.

Many fast-fashion companies boost profit margins by shaving labor costs and upholding inhumane standards. A 2024 report from Public Eye, a Swiss consumer awareness group, found that employees in Shein factories averaged 75-hour workweeks.

Furthermore, these grueling labor practices sometimes lead to deadly consequences. In 2012, more than 100 workers died in the Dhaka, Bangladesh, garment factory fire due to a lack of appropriate health and safety measures, including emergency exits.

Between carbon emissions and excess waste, the industry also wreaks havoc on the environment. In 2018 alone, more than 11 million tons of textile waste ended up in landfills. The “throwaway culture” around fast-fashion garments means they often end up in the trash after the trend goes out of style. Rampant environmental racism also means clothing waste and other forms of pollution disproportionately impact individuals from Black and Hispanic communities — something advocates have been raising the flag about for decades.

Fast fashion also accounts for a whopping 10% of annual emissions globally, according to a March 2023 report from the United Nations Environment Programme. That’s more than the aviation and shipping industries combined.

Asia is home to leading apparel producers

As an industry, the leading fast fashion producers are found in countries where cheap labor and a high economic reliance on exported products. Today, just a small handful of nations produce the vast majority of clothing Americans wear — and, in turn, those nations expect a certain amount of demand from consumers.

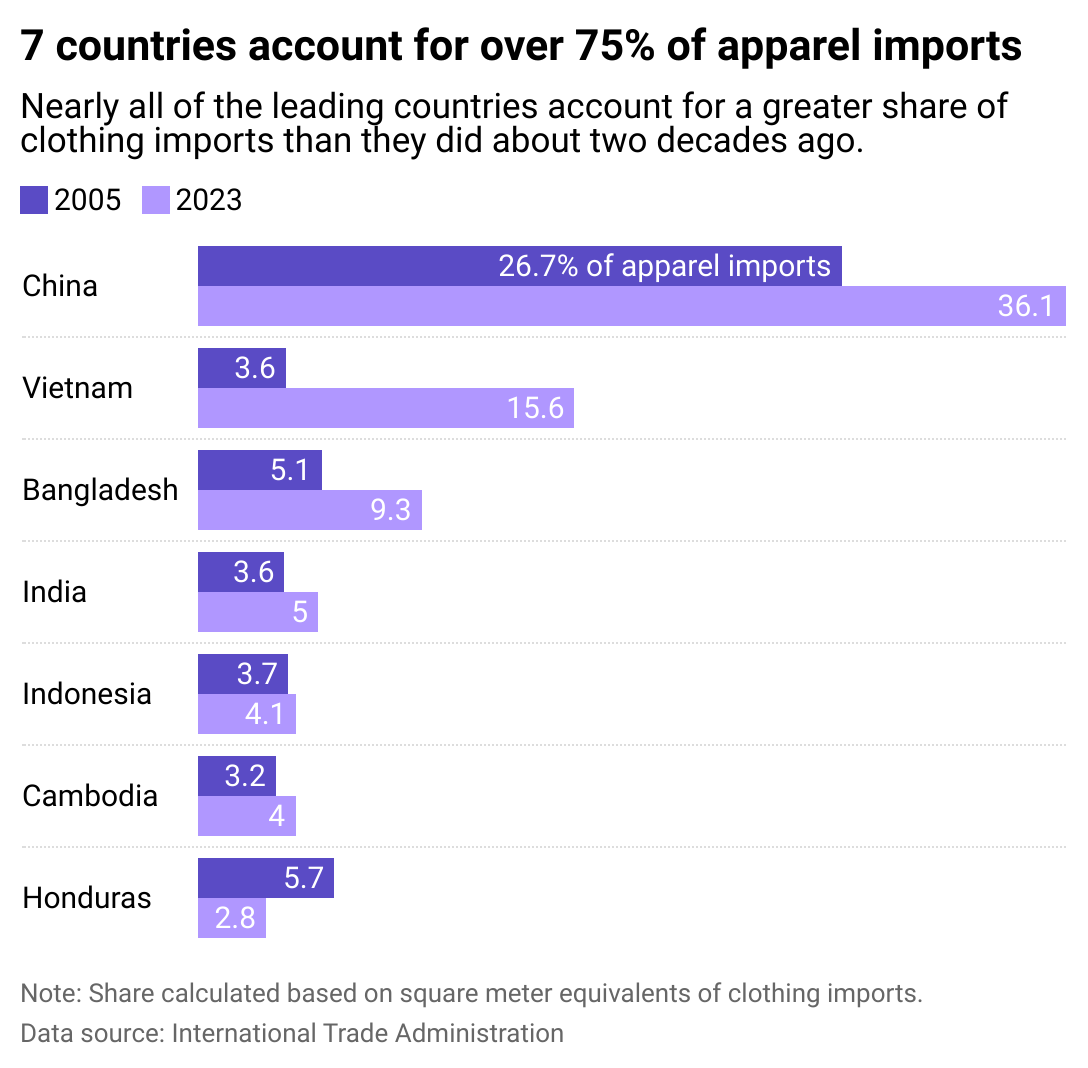

In 2005, 14 countries produced more than 75% of the clothing imported to the U.S.; less than 20 years later, though, only seven countries do the same, with China, Vietnam and Bangladesh topping the list. Meanwhile, North American countries like Mexico, which provided nearly 8% of clothing imports in 2005, have fallen behind.

As a result, clothing exports have become economic pillars in certain countries. McKinsey reported the ready-made garment sector accounted for 84% of Bangladesh’s exports as of 2021, meaning that a blow to the market could severely impact the country’s economy. And as some nations, including France, have banned fast-fashion advertising or limited its circulation to thwart its environmental and social impacts, industry changes may arrive sooner than expected.

Vulnerable to a shaky supply chain

The countries that supply fast-fashion brands aren’t the only ones in a precarious position. In the U.S., outsourcing the vast majority of the clothing market has left the nation heavily reliant upon just a few nations to produce the garments most Americans wear. As a result, economic and political issues can easily disrupt the production and availability of clothing.

In 2023, for example, apparel imports dropped to lows not seen since the pandemic as trade tensions arose between China — the world’s #1 clothing supplier — and the U.S. Plus, economic factors at home, including soaring inflation, saw purchasing power decline.

With these detrimental consequences in mind, the end of fast fashion may not be a question of if, but when. As consumers gain awareness about the unseen costs of buying cheap clothes, many have already discarded fast fashion, with some urging others to do the same. That includes celebrities like Chappell Roan, who spoke out against H&M in September 2024.

But consumers have grown accustomed to cheap, trendy, and readily available clothes. And for shoppers who can’t shell out hundreds of bucks for high-end outfits, brands like Shein that offer almost identical dupes can be hard to resist. As of June 2024, a typical dress from Shein costs less than $30. When that dupe inevitably wears out, shoppers can simply buy a new one to fit the next trend.

Time will tell whether fast fashion loosens its grip on the U.S. clothing industry. Though fast-fashion companies like Shein and H&M claim to have implemented more eco-friendly policies, such as using artificial intelligence to reduce garment waste, many customers remain skeptical. Legislatures like the rulings seen in France could transform the industry even further.

In the meantime, help break the cycle of consumption and waste by approaching clothes shopping mindfully, purchasing from sustainable brands wherever possible, and reducing clothing waste by either donating or recycling. A 2022 report from the Berlin-based think tank Hot or Cool Institute recommends that those living in high-income G-20 nations take measures to make clothing last and limit purchases to just five garments per year to support global warming prevention.

Better yet, only buy the amount of clothes you actually need, rather than the amount you might want.

Written by Cu Fleshman. Data work by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on The RealReal and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio. The article was retitled and copy edited from its original version.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.