El Dorado County is famously recognized as the place where California’s Gold Rush began. According to historical accounts, on Jan. 24, 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold on the south fork of the American River in the valley known to the Nisenan Indians as Cullumah (beautiful valley). That momentous instance not only helped shape California’s future, it reinvigorated the country’s economy as well.

Toward the end of the 1880s another historical, albeit little-known, event transpired in El Dorado County — the public hangings that sent shock waves across Placerville.

Based on newspaper articles at the time, a reputedly wealthy farmer John Lowell was murdered on March 24, 1888, during a robbery at his ranch near Mormon Island in El Dorado County. Three men were convicted of first degree murder — John Henry Meyers, a 27-year-old immigrant from Germany; John Olsen, a 24-year-old Norwegian native immigrant; and William Drager, a 41-year-old immigrant from Germany.

Meyer was hanged on Nov. 30, 1888. Olsen and Drager — who steadfastly claimed throughout the trial that they weren’t involved in the murder of Lowell — were hanged on Oct. 16, 1889. These were the last legal hangings and among the last public executions in California.

Hangings were not uncommon in the United States back then; Placerville had been referred to as “hangtown” since the Gold Rush days. However, Olsen and Drager’s sentence galvanized the whole town into action because Placerville residents felt they had not been complicit in the murder, and the death penalty was too harsh for their actual crime.

Over 425 townspeople — including the district attorney who prosecuted the case, the sheriff, and nine of the 12 jurors — signed a petition requesting the sentence be reduced to life imprisonment. It was, however, rejected and the pardon turned down. It fell upon El Dorado County sheriff James Madison Anderson to carry out the sentence and, for years, that an injustice might have been done weighed heavily on him.

His great-great-granddaughter M.G. Rawls — a retired Pasadena lawyer and author of fantasy trilogy books “The Sorts of Pasadena Hollow” — delves into this event and gives readers an intimate look at the victim, the killers, the crime and the hangings. She chronicles the details of the case and then reaches her own conclusions about this long-forgotten and rarely discussed episode in Placerville’s past in her book called “Hanging Justice,” scheduled to publish in October 2025.

In the course of her extensive research, Rawls traveled to El Dorado County several times and visited the gravesites of her ancestors at Placerville Union Cemetery. During one of her trips there she found out about Save the Graves.

Conceived in 2019 by Mike Roberts and his wife Michele Martin, Save the Graves is a nonprofit organization with a mission to restore, preserve and celebrate El Dorado County’s historic cemetery and the stories they contain.

Speaking by phone, Roberts begins just as he does all his talks about Save the Graves: “Some people discover at some point in their lives that they have a peculiar fondness for old cemeteries. And I am one of those people. I’ve always been fascinated by them and drawn to them. It turned out there’s a word for people like us — taphophiles.”

“When I was walking my dog one day, I came upon this cemetery near my home and realized that what was once a beautiful place had gone to seed,” Roberts recounts. “No one was cutting the grass and the trash cans were overflowing. There’s so much history beneath these headstones yet no one was taking an interest in preserving it. So I took it upon myself to do that.”

Roberts explains, “There are several ‘Friends of’ organizations in several cities, so I tried to create Friends of Union Cemetery. To attract people into joining the group, I wrote a piece about the history of Union Cemetery, had it published in the local paper, and apprised readers that I was holding a couple of formation meetings and gave the times and dates.

“One of those people who showed up was a retired PR executive for a utilities company who told me he was part of something similar to this in Long Beach called Save the Graves,” Roberts recalls. “The Historical Society was involved and they did theatrical portrayals of local historical characters buried in the cemetery. They researched and wrote scripts; the actors rehearsed and wore costumes authentic to the era. They charged money for the performances which people loved because they learned about the town’s history; that enabled them to raise funds to restore the cemetery. He had already committed to do some work for the Placerville Park but offered to help as soon as he finished that project.”

“I had forgotten about it until he called me two years later and asked if I was still interested in collaborating,” Roberts continues. “Coincidentally, a theatre professional he had previously performed with in Long Beach had just arrived in Placerville and he recruited him to get involved. They got us a grant and the three of us partnered up and launched our first production. As challenging as it was to stage a show at a cemetery, we pulled it off and it was very well received in the community. We held the second production and then we had a pandemic.”

These two gentlemen Roberts teamed up with eventually moved on to do theatrical productions elsewhere, leaving Roberts to focus on his original objective.

“I was everywhere doing fundraising and cemetery improvement projects, running volunteer groups, as well as doing repair and restoration work myself,” Roberts says. “What bothered me most were the broken headstones. The county that managed the cemetery wouldn’t let me touch anything because of the liability. Heaven forbid the county gets sued by someone because I cleaned their ancestor’s grave! So I circumvented a potential lawsuit by checking the genealogy of the people buried there and choosing to repair the headstones of those with no relatives in Placerville.”

Using money they’d raised, Roberts paid $3,000 to a sympathetic local cemetery operator who agreed to get 18 of the headstones off the ground. And that made a huge difference. Instead of merely explaining to people what he was trying to accomplish, it gave him something concrete to show when he asked for donations. It also made fundraising easier the following year.

According to Roberts, the real fundraising vehicle is the program for the annual event. They started out with a four-page leaflet and last year they printed a 48-page magazine with a glossy cover and inside were advertisements about local shops and proprietors interspersed with the schedule of activities.

These days, when Roberts tries to sell advertising space he’s asked about readership and circulation figures, which makes him laugh. He no longer has to do door-to-door solicitations; he reaches out by email. But when he does go out to see potential advertisers, he’s always wholeheartedly welcomed. People comment on how beautiful the cemetery looks.

In the six years since he established Save the Graves, Roberts has become something of a local luminary. He attends the downtown merchants association meetings and listens to some of the problems they encounter and helps find solutions. He has been giving two-hour talks about Save the Graves before various groups.

“Last year we incorporated Save the Graves as a non-profit organization and that enabled us to apply for funding and we got our first big one — a $5,000 grant,” Roberts says happily. “The County Board of Supervisors gave us $10,000. We’ve been receiving donations from many people in the community, I’m so humbled. This year one of the descendants of a Placerville sheriff also sent us money. I didn’t know we had prominent historical figures in our town – we’d lost track of them.”

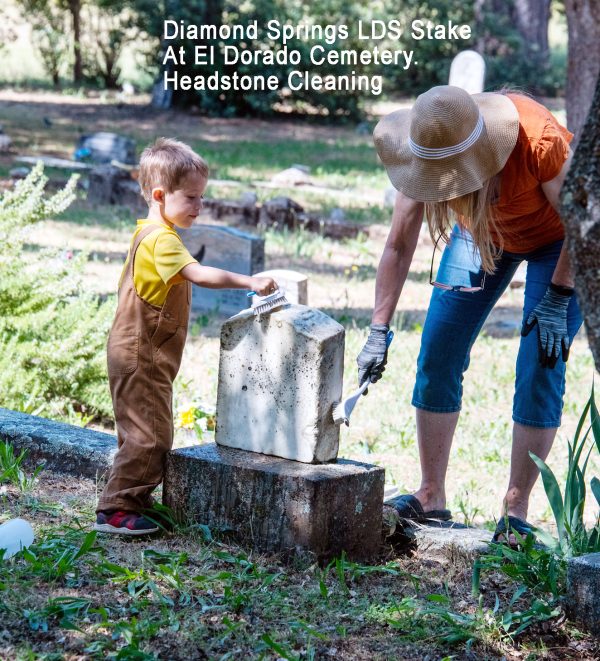

“We now have the luxury of having the money to take care of the cemetery,” Roberts declares. “The headstone cleaning can be done by volunteers so the funds go into fixing more complicated issues, like accessibility and terrain problems, crumbling copings along the walkways, etc. We’ve gotten a lot of damaging lichens out of old headstones and we’ve posted all sorts of interpretive signs that tell stories of these places to engage people who wander through.

Roberts emphasizes, “Save the Graves is as much about building community as it is about fixing the cemetery. Historic cemeteries strengthen the fabric of our community by building connections between people. Part of that requires that you know something about those who are buried — and we accomplish that through our theatrical productions, biographical stories we post and a Find the Grave QR code the general public can scan with their smart phones. We’re building connections to the people who are here now and to the place they live — that’s community. It starts to grow and we eventually connect with each other.”

“Placerville’s demographics are shifting with folks from big, congested cities moving in because they can buy an acre of land and enjoy nature and wildlife. And guess what else they like — old cemeteries! And they’re willing to help out,” Roberts enthuses.

Two of those transplants to Placerville are Jacob Rigoli and Sean Manwaring with whom Rawls got acquainted when she went to see the house her great grandfather used to live in — which they now own. “Jacob and I first met Meg in October 2021. At that time we were restoring the historic residence colloquially known as ‘Judge Thompson House,’ named after her great grandfather, Superior Court Justice George Thompson,” Manwaring says. “It was also the childhood home of her grandmother Virginia Thompson Gregg. Before that, her great-great-grandparents lived in the circa 1862 home, making it the residence of three generations of her family. Her mother and uncles visited the home in their youth with her grandmother.

“It was Meg who introduced us to Save the Graves,” Manwaring clarifies. “The following year, we joined the planning committee and assisted with the annual event and fundraiser. Although I’m not a Placerville native, I grew up in Northern California, frequently visiting old mining camps and Gold Rush towns with my family. I have fond memories of Placerville. Like her, my husband Jacob and I are descendants of pioneers who arrived in California either just before or during the Gold Rush.

“We quickly bonded with Meg over our shared enthusiasm and deep appreciation for all things related to early California history. Since then, she has become a dear friend, and we truly understand her passion for preserving her family’s legacy,” states Manwaring.

“The work of Save the Graves is vital in preserving not only our local history but also the stories of California’s pioneering women,” informs Manwaring. “Last year, we featured one such remarkable figure: Mollie Wilcox Hurd. Born in Placerville in 1870, Mollie’s life took an unexpected turn when she married Frank Stoddard, nephew of Elizabeth Stoddard Huntington, the first wife of Central Pacific Railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington.”

Collis P. Huntington’s nephew, Henry Huntington, and his wife Arabella founded Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens – a beloved institution in the San Gabriel Valley in Southern California.

“Frank’s family connections and career in the railroad industry propelled Mollie into the elite social circles of Los Angeles,” Manwaring continues. “While in Los Angeles, she served as President of the Los Angeles Florence Crittenton Home, which was established to help women and children in need. Beyond raising their two children, Mollie dedicated herself to philanthropic endeavors, particularly advocating for women’s and children’s rights. She played a pivotal role in securing state legislation requiring fathers to pay child support regardless of marital status.”

Mollie and Frank Stoddard were married for 25 years. Following her divorce from him and after their children had grown, she married her old friend – Los Angeles area senator, Henry M. Hurd. She remained deeply connected to her Placerville relatives. She was a founding member of the Placerville Shakespeare Club, generously bequeathing a donation to build their historic building upon her death in 1929. Mollie and Senator Hurd are both buried in the Placerville Union Cemetery.

“This year’s show called ‘Law and Order,’ to be held on Oct. 19, will focus on four notable crimes that occurred in El Dorado County between 1855 and 1903,” he explains. “Each crime will be presented through historical portrayals, featuring two key figures — ranging from perpetrators to victims, and from law enforcement to members of the press. Attendees will gain insight on both the community and the justice system.

“The portrayals are historically accurate and performed graveside — often near the burial sites of the pioneers being depicted — and actors wear period costume,” describes Manwaring. “One featured crime is the John Lowell murder of 1888, in which Meg’s great-great-grandfather Sheriff James Madison Anderson testified during the trial and guarded the accused. Additionally, her great-great-uncle, Marcus Percival Bennett, served as the district attorney. The case haunted both men for years.

“Jacob and I contributed to the research and organization for this year’s event,” Manwaring adds. “He will serve as a stage manager and I’ll portray Marcus Bennett. We are just two of the many volunteers who help put on this annual event at Placerville Union Cemetery. Mike and Michelle are the driving force behind the fundraiser that helps preserve the cemetery and the stories of those buried there.

“Meg’s research has unearthed a forgotten story,” concludes Manwaring. “It’s fascinating to discover the events that shaped the townspeople and the motivations of those involved in the John Lowell murder trial. She’s helping our community discover this important chapter in our history.”

Indeed a significant event transpired over a century ago at Placerville that residents there today may know nothing about. Roberts admitted as much when he said he didn’t know about Sheriff Anderson. But through the organization he and Martin created, they are learning about these episodes in their local history and making them unforgettable.