In Southern Arizona, on an over-100-degree day in June, humanitarian aid workers found a group of migrants standing in a thin slice of shade formed by the large steel slats of the border wall. Among them were a pregnant woman, an elderly woman, two women showing signs of heat exhaustion and young children. In total, about 30 people had crossed into the United States and were waiting for the Border Patrol to pick them up so they could make an asylum claim.

They were some of the lucky ones. Advocates told The 19th that more and more people are ending up stranded in the desert because of onerous Trump and Biden administration restrictions that make it difficult to ask for asylum at official ports of entry. Instead, people are trying to cross through remote desert areas.

That’s a risky decision year-round; the desert can be disorienting and people can get lost, injured or fall prey to criminal organizations that operate on the Mexican side of the border. But in the summer, that decision can be deadly for another reason: Temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit without reliable water sources. Even for migrants waiting to make asylum claims on the U.S. side of the border, “you are going to be waiting against a very large 30-foot-tall, heat-conducting wall, with very little in the way of shade,” said Brad Jones, a volunteer and media liaison with Humane Borders, whose members encountered the asylum seekers by the border and countless others in the Arizona desert.

Crossing the desert is a dangerous gamble, but often the only option left for asylum seekers after their long and arduous journeys from places like Venezuela, Honduras, Guatemala and Haiti, which are beset by violence, political instability and poverty.

“We know, based on 20-plus years, that the harder you make it, the greater the risks that they will take in the desert, whether it is in Texas or Arizona,” Jones said. “It means that risk-taking exponentially increases the likelihood you will die.”

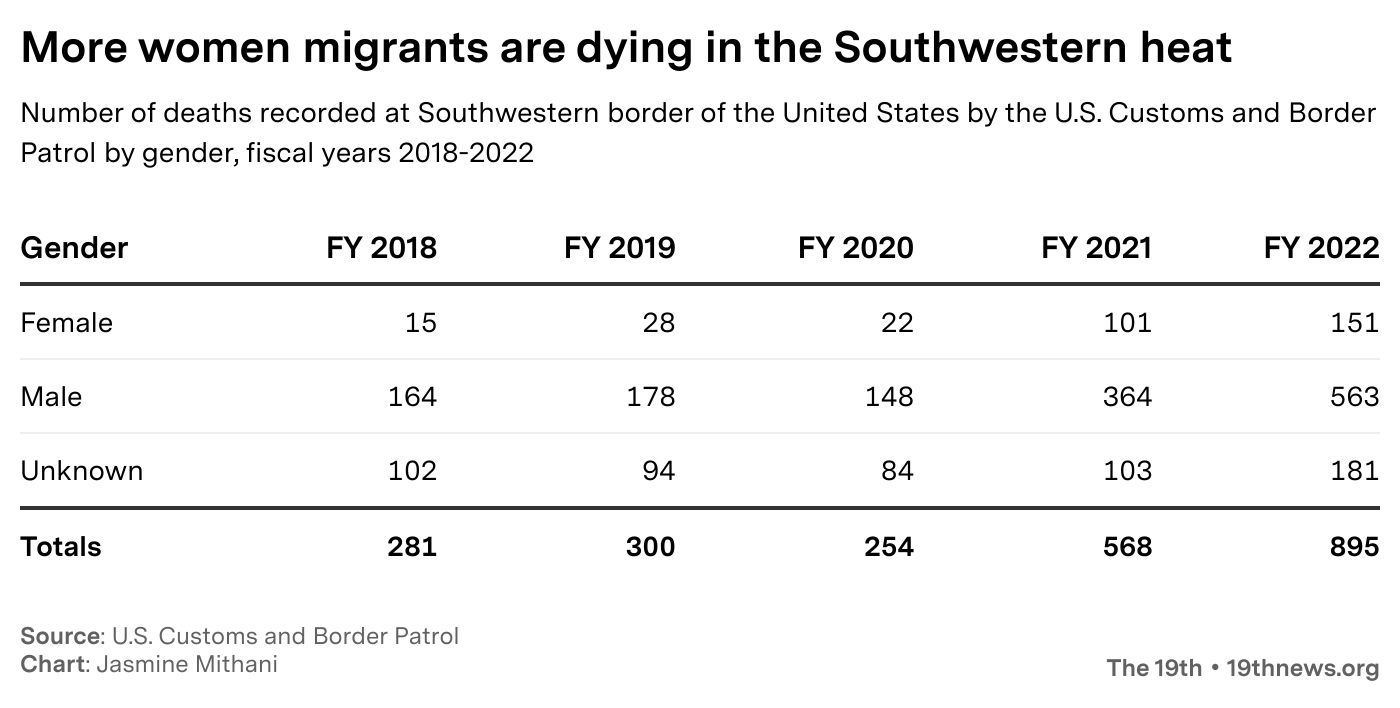

Historically, men made up the majority of those dying in the border desert. But in recent years, the balance has shifted. Increasingly, those dying are women.

For the last several decades, those crossing the border into the United States were mostly Mexican men looking for jobs, said Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. But starting around 2010, that began to shift, with people from other countries making the trip more than in previous decades, as well as more families. Experts say these demographic changes could also explain the shift in demographics of migrant deaths.

In April, No More Deaths, a humanitarian aid organization, issued a report quantifying the changes in who is dying while trying to cross the border. The report examined deaths in the Border Patrol’s El Paso sector, which covers southwest Texas and the bootheel of New Mexico. In 2023, the group documented 140 deaths in that area — 31 more than in 2022. Of those, 51 percent were women. It’s the first time that data captured anywhere along the border has indicated a higher number of deaths for women than men.

And across the board, the number of women who die appears to be rising. According to the Humane Borders’ Migrant Death Mapping, a partnership with the medical examiner’s office in Pima County, Arizona, that tracks deaths in the state’s border desert region, 38 women were found dead in 2023 — or 22 percent of all cases. Just the previous year, women made up 15 percent of all deaths. Between 2010 to 2020, they accounted for approximately one in 10 deaths.

Melanie Nezer, vice president of advocacy and external relations for the Women’s Refugee Commission, said women are driven to migrate for the same reason as men: lack of employment, persecution by local armed gangs and, increasingly, climate change, which is affecting farming yields and food security. Climate-intensified disasters have also led to high levels of displacement around the world and are linked to higher rates of domestic violence and sexual assault in their aftermath.

All these factors interact in ways that can lead a person or a family to migrate. “A lot of times when you’re talking about women, you’re also talking about children,” Nezer said. Women, she said, “don’t want their kids to be forcibly recruited by gangs. They want their kids to be able to grow up and go to school and work and have a future.”

Myriad reasons why more migrants are dying

According to the No More Deaths report, many of the deaths in the El Paso sector in the last year were related to environmental exposure, dehydration and hyperthermia, a term used to describe heat illness. In data going back to 2014, the report also included migrants who died trying to climb over the border wall, among them a 19-year-old pregnant Guatemalan woman who died in 2020, or by drowning in canals. It also noted deaths involving the Border Patrol, in which migrants died while in custody, while being chased or by use of force.

The data in the report comes from medical examiners’ offices, news sources and from the volunteers themselves, who find remains out in the desert every year while they are leaving food and water along the trails used by migrants. The tally is different from the number the U.S. Customs and Border Protection provides. In most years, No More Deaths documented a higher number of deaths than the federal agency. One exception is 2023, when CBP registered 149 deaths in the El Paso sector. On its website, CBP says that “statistics are pulled from designated target zones, which comprise 45 counties along the southwest border.”

Any figure is also likely an undercount — in part because of the vastness of the U.S.-Mexico border, which spans nearly 2,000 miles, and because of how animals and the elements scatter remains.

In the 1990s, the United States implemented a “prevention through deterrence” border strategy aimed at funneling migrants away from cities by concentrating more agents in urban hotspots. This forced people “over more hostile terrain, less suited for crossing and more suited for enforcement,” according to the plan details. Advocates say this is why so many people die making the trek in the first place.

Since 1998, the Border Patrol has recorded over 8,000 deaths along the border, with a majority occurring in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts, located in Arizona and New Mexico, respectively. Last week, the agency reported three deaths in the Sonoran desert, including a 17-year-old girl.

Advocates believe the growing number of deaths in El Paso and elsewhere along the border stems from a combination of two things: changes in asylum requirements converging with the growing number of asylum seekers. Asylum is a form of protection given to people fleeing persecution over identifiers like their religion and race or for being a part of a certain social group. Unlike refugees, who are granted permission to enter the country ahead of their arrival, asylum seekers request protection once they are already in the country or at ports of entry, which are the official entry and exit points into a country. To start the process, migrants have to undergo what is known as a “credible fear” interview, where an asylum officer determines if they meet the minimum threshold to request asylum.

As the number of people migrating across the world has continued to climb, actions by both the Trump and Biden administrations forced many migrants to stay in Mexico while their asylum claims are being processed. In June, faced with intense political pressure from Republicans — in an election year where immigration and the border rank as top-of-mind issues to voters — President Biden swung right. He issued an executive order that triggered a ban on migrants requesting asylum between ports of entry if the southern border is experiencing over 2,500 crossings a day. The order also raised the bar for migrants seeking protection, and requires migrants to voluntarily share or demonstrate their fears of persecution before being asked by a Border Patrol officer in what’s known as “the shout test.”

A requirement implemented last year remains unchanged: Asylum seekers must first make an appointment through an app called CBP One and wait in Mexico. The problem is that it can take many months to get an appointment. And the longer people have to wait, the more desperate they become. In an interview, Bryce Peterson, a volunteer with No More Deaths who helped compile the report, said he recently visited a migrant camp in Ciudad Juarez, the Mexican city bordering El Paso, where there is very little sanitation and no cooling system, so temperatures were consistently over 100 degrees.

Staying in Mexico is also very dangerous, Nezer said, as migrants are essentially sitting ducks for organized crime. “The shelters are completely overwhelmed, and security, particularly for women and children, is a major issue. Extortion, sexual violence, kidnapping — all of those things,” she said. “At some point, if they’re waiting for an appointment that may never come, they make the decision to try to enter wherever they can, with the plan of presenting themselves to border authorities once they cross.”

While there aren’t official stats breaking down how many asylum seekers coming to the United States are women, anecdotally, Peterson and Jones say they are seeing more women crossing — and more women with families. And because they initially come to seek asylum, these people may be less prepared for a desert crossing and not as aware of the dangers of heat.

Now with even more asylum restrictions in place this summer, advocates are wary of how many will then take the chance as summer temperatures continue to climb. “Our biggest concern is that asylum seekers are just going to take greater risks,” Jones said. “That means entering in more remote areas to get into the country. That is our biggest concern. Border policy sometimes incentivizes risk.”

Migrants crossing desert face border patrols and deadly extreme heat

Recent measures by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, who ordered the placement of concertina wire along the Rio Grande and deployed state troopers and the Texas National Guard to patrol the border, may be pushing more people to cross through the El Paso sector, Peterson said.

Around El Paso, average temperatures are typically in the 90s during the hottest months, which are June, July and August. But heat records in the region keep getting shattered. In 2023, there was a 44-day stretch of 100-plus temperatures in El Paso, which broke the previous record of 23 days in 1994. Last year, Tucson, a southern Arizona city about an hour’s drive from the border, also broke its own record: 15 consecutive days over 110 degrees.

Extreme heat can become deadly in a matter of hours, causing a person’s heart to pump faster in order to circulate more blood to the skin’s surface in an effort to cool the body down, which can lead to a heart attack or organ failure. Heat also causes sweating, the body’s natural evaporative cooling mechanism; in extreme cases, that can lead to dehydration and kidney failure. Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat because they have a harder time controlling their body temperature and get dehydrated more quickly. Extreme heat is also linked to a higher rate of preterm birth and miscarriage.

In the El Paso sector, according to the No More Deaths report, most of the deaths are occurring near neighborhoods and densely-populated areas. But in Arizona, Jones said, some people who opt to cross can become frustrated with the wait at the border and choose instead to walk across the desert.

“It’s a recipe for death,” he said. “There is no potable water apart from the water stations we maintain. And stumbling upon those is like a needle in the haystack. So we go to great lengths to put the word out: Do not venture out on your own, because you may not be coming back.”

Written by Jessica Kutz.

This story was produced by The 19th and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.

Re-published with CC BY-NC 4.0 License.