In 1919 D.W. Griffith directed Hollywood’s first onscreen interracial love story between a white woman and a Chinese man. The movie was “Broken Blossoms” and the lovers were played by Lillian Gish as Lucy Burrows and Richard Barthelmess, in yellow face make up, as Cheng Huan.

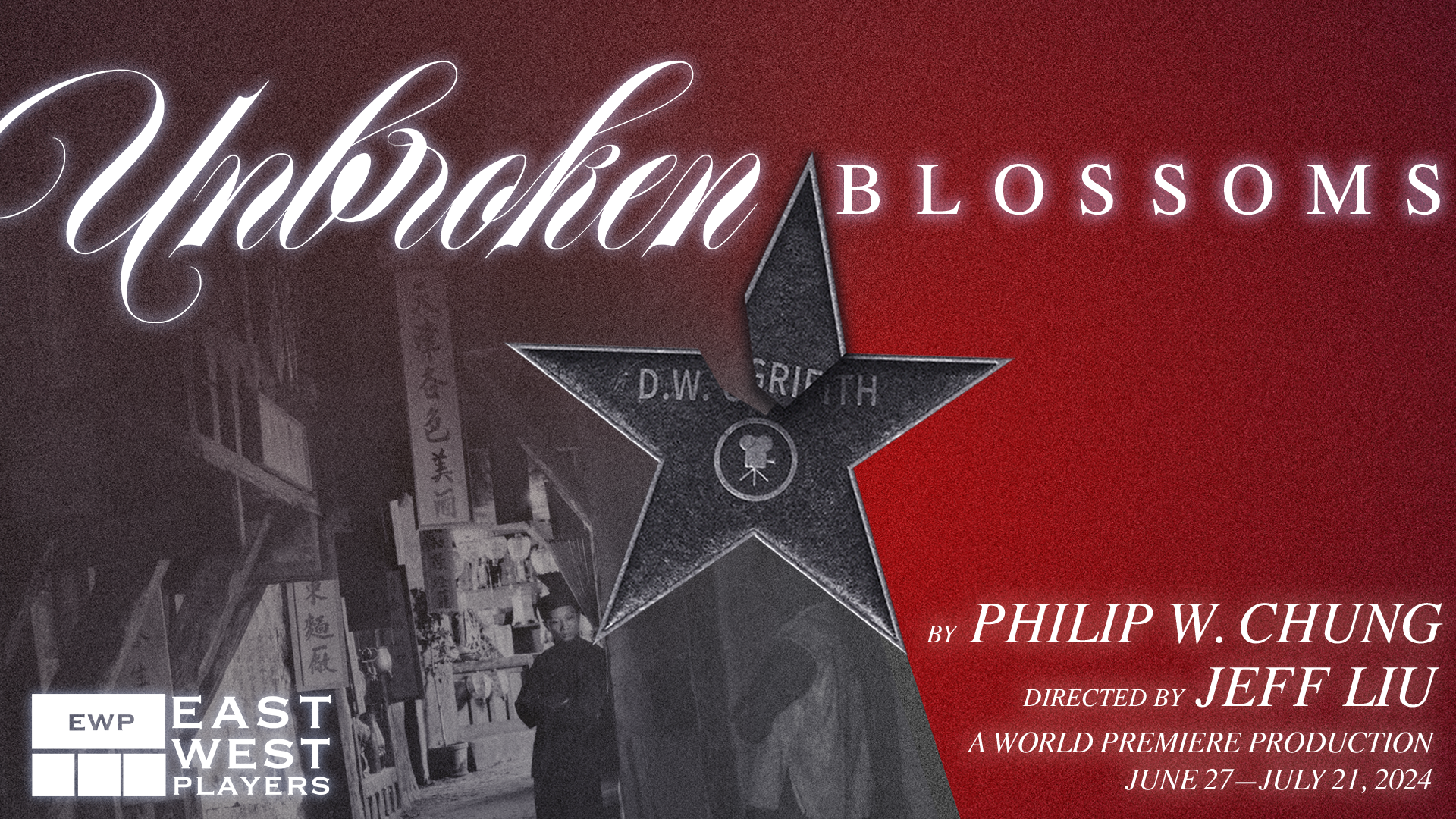

What went on behind the scenes is the subject of East West Players’ next World Premiere play “Unbroken Blossoms” — a historical reimagining of the making of this actual boundary-breaking Hollywood classic — written by Philip W. Chung and directed by Jeff Liu.

“Unbroken Blossoms” follows two Chinese American consultants who are hired for the movie “Broken Blossoms” — Moon, an idealistic family man and James, a cynical, aspiring filmmaker — as they contend with the inflated ego of the film’s director D.W. Griffith, who is hoping to disprove criticisms of racism after the release of his controversial Civil War epic “The Birth of a Nation.”

Based on real events, this story of the suppressed voices behind the silent film “Broken Blossoms” reveals a historical conflict just behind the silver screen. “Unbroken Blossoms” goes on stage from June 27 through July 21 at the David Henry Hwang Theatre in downtown Los Angeles. The cast includes Gavin Kawin Lee as James Leong, Ron Song as Moon Kwan, Arye Gross as D.W. Griffith, Alexandra Hellquist as Lillian Gish/Gilda, and Conlan Ledwith as Richard Barthelmess.

Speaking by phone, Chung explains the genesis of the play. “I’m fascinated by Hollywood history so I’ve read about D.W. Griffith; he is considered the godfather of cinema. His film ‘Birth of a Nation’ is hailed as one of the first and greatest films of all time. But it’s also a movie that makes heroes out of the Ku Klux Klan. It says something about America that the film which defined Hollywood — it introduced new forms and techniques about the craft — had KKK as protagonists. I thought it was interesting.”

“Studying his career I realized that he made ‘Broken Blossoms,’ one of the first ‘positive’ interracial relationships in Hollywood films, after that,” Chung continues. “But, of course, it was 1919 and it was a white man in yellow face makeup playing a Chinese character. I watched the movie and from today’s point of view it’s very dated and offensive because of the stereotypes. So one has to look at it from the historical context. For that time, this was a progressive movie — it was arguing for this relationship between a white woman and Chinese man. They were clearly trying to do something that wasn’t the usual negative depiction of Chinese people. The intent might have been good but, because of the limitations at that time, the result was still problematic.”

“And then I found out during my research that he hired two Chinese American consultants for the movie — James Leong and Moon Kwan,” adds Chung. “They were both real people and went on to have long careers working in Hollywood films. But we don’t really know much about that history and a lot of it is forgotten. That got me thinking about what it might have been like to work on this movie at a time when the Chinese were being portrayed but not in an authentic way. ‘Unbroken Blossoms’ tries to explore both sides of that dichotomy. It’s an imagining of what transpired from their point of view.”

Chung finished writing a draft of “Unbroken Blossoms” in 2015 and the play had a public reading of it at the Japanese American National Museum with East West Players and Visual Communications. He put it away after that and worked on other projects. It was during the pandemic that he revisited and reworked the play.

“The world has changed a lot since I wrote ‘Unbroken Blossoms’ in 2015,” explains Chung. “The play is set in 1919 in Los Angeles during the Spanish flu pandemic. It was very similar to COVID: people were wearing masks and there were several race riots — black versus white — and anti-Asian violence all over the country. Those were the things in my play, but when I wrote in 2015 those were events that happened in the past. I wanted to explore that parallel between now and 1919 more closely than I did in the original version. The fact that the play feels more relevant now than it did back in 2015 is strangely disappointing in a way, because it shows that history is repeating itself and we didn’t learn from past experience.”

That Chung called his play “Unbroken Blossoms” hints at something hopeful, though. He discloses the idea behind the title. “The white woman and Chinese man in the 1919 film are broken blossoms. Each has tragedies in their lives that prevent them from being a whole person. I thought it would be interesting if the play was the opposite of that. Is there a way to become unbroken — specifically in this case — if the portrayal of being Asian is a broken version of ourselves that we see from Hollywood? Is there a way beyond that?”

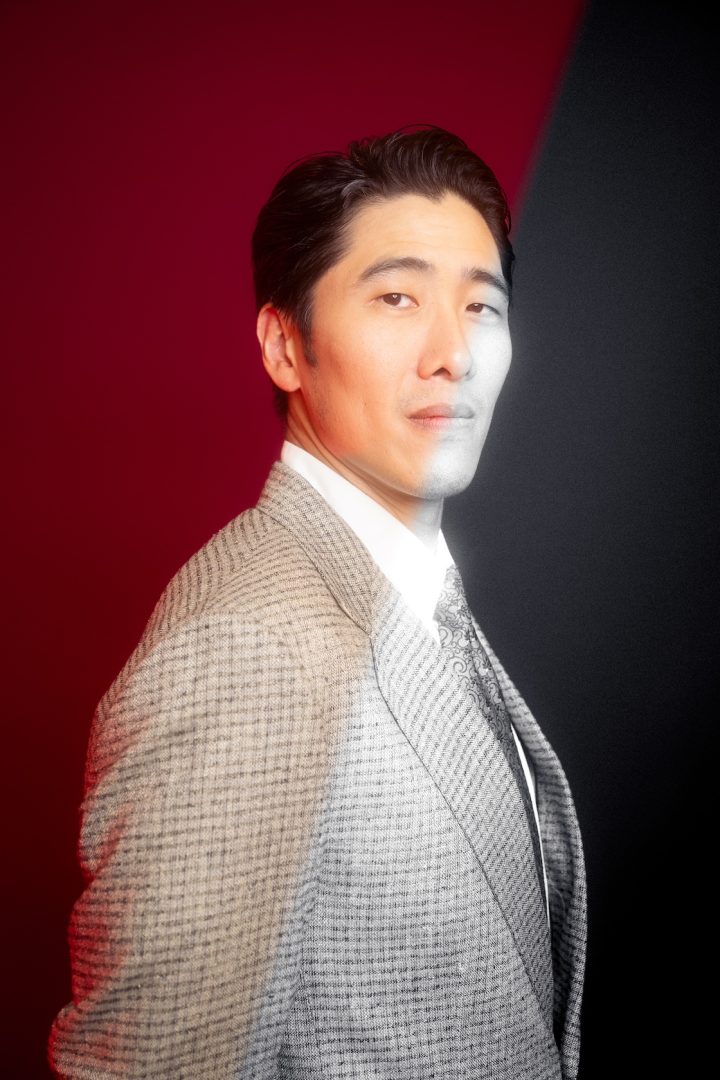

Gavin Lee, who plays James Leong, heard about Chung’s play in February through “Unbroken Blossoms” director Jeff Liu. He says, “I had worked with Jeff before and he asked me if I was interested in reading a new play. He sent me the script and I thought it was pretty visceral. There are many elements in the play, like the misogynistic laws at that time, that got me angry. But they are obviously meant to have that effect. There are some scenes that were difficult to read — particularly the part where Moon gets mistaken for me and he gets brutally beaten. They can’t tell the difference between the two Chinese men.”

“Anyone who watches the play will definitely feel for the two Chinese consultants,” states Lee. “They have vastly different viewpoints. My character is very cynical. Already he knows the filmmakers don’t really care about them or their opinions; they were only hired because the producers want to look good. My character understands that whole process and he’s just trying to get something out of it. Moon, on the other hand, really believes he’s there to be a consultant. I feel like he’s the one the audience will root for.”

“Moon and James poke at each other because Moon believes he’s helping to make the characters be more authentic and represented in this film,” Lee relates. “James, on the other hand, believes the only way the film can be more authentic is if it has an actual Chinese actors instead of white actors portraying Chinese people. So Moon laughs at what James is trying to do; he thinks it’s unrealistic and wishful thinking.”

Two weeks into rehearsals, Lee reconsiders his initial reaction about his character. “When I first read the play, I saw James as being cynical. The more I work on it, though, I’m finding parts in which his love, passion, and hope show through his sardonic exterior, which is fun to play. I’m not sure if this was the intention of the author, Philip Chung, or if it’s just a character trait I had to apply myself to get more grounded in it. But it does make me want to root for James more. While he seems cynical, James’s ultimate goal is to learn from a renowned director so he can make films that are true to Chinese people.”

Lee didn’t set out to be in theater. He reveals, “I had always been into math and sciences — or at least that was what I thought. I was on a pre-med track going into college and I had taken the MCAT. But about ten years ago, I decided that medical school wasn’t for me. I had switched from pre-med to teaching and was living in Korea then. I took an interest in acting after reading career guide books and taking personality tests which showed it was the best career for me. I thought it was strange, but I tried it out on a web series. I had no training so I was awful. As bad as I felt about my acting, though, I actually loved doing it.”

“So I moved back to the U.S. and almost immediately I signed up for acting classes,” says Lee. “I went to the Beverly Hills Playhouse and took a course on scene study. Then I did my first play in 2016. I have also done some TV and film but theatre has become a strong passion for me.”

“I feel that there’s better representation in theatre than TV or film. But that’s only my opinion and it’s based on my lived experience,” Lee clarifies. “I get audition calls for roles for open casting. In fact, I have another audition to play a British character. I think theatregoers are more accepting seeing a non-white actor portraying a traditionally white character.”

As for the audience takeaway, Lee opines, “Whether people believe one viewpoint or another, any good play will have them contemplating the repercussions of what they saw. Some people may disagree with the message of the play but I definitely think people will come out after seeing the play feeling a flurry of emotions — which is why we do theatre. There’s comedy in it, obviously drama, anger, which is one of the feelings I had when I read Philip Chung’s play. Ideally, some people will leave the theatre hopeful that because times have changed in the last hundred years, it will continue to do so for the better.”

While it’s unfortunate that Chung didn’t find much information about Moon and James and their experience, it’s also propitious. Having a blank canvas accorded him the freedom to create nuanced, complex characters and the engrossing plot that make Unbroken Blossoms compelling theater.