Most American diners and food enthusiasts know that Wagyu beef makes the best steaks and other meat dishes. After sushi and ramen, it is the latest Japanese food to gain popularity in the U.S. Unlike sushi and ramen, though, it can be found on every American steakhouse’s menu and not just at Japanese restaurants. And we value Kobe – Wagyu beef from black cattle raised in Japan’s Hyogo Prefecture – for its flavor, tenderness, and perfectly-marbled texture. It can be prepared as steak, sukiyaki, shabu-shabu, sashimi, and teppanyaki.

The company behind the Japanese cuisine that largely changed the American culinary landscape is Mutual Trading Co., Inc. It was founded in 1926 as a co-op by several Little Tokyo businessmen to import commodities from Japan, including kitchenware for home use and foods – mostly dried and canned. Though the company ceased operations during the war, recovery afterward was quick and it flourishes to this day.

In 1989 Mutual Trading held its first Japanese Restaurant show as a modest chinaware sale held at their warehouse area and parking lot. Their staff designed and produced the event – from the theme that changed yearly, to product selection, to seminar highlights – and even procured special items aimed at filling customers’ needs. It was so successful that in 2013 they had to find a larger venue. (Read related story about the company’s growth and its role in the evolution of Japanese cuisine)

After a four-year absence because of the pandemic and post-Covid health and safety concerns, Mutual Trading returned to the Pasadena Convention Center on Sept. 23 for the 32nd annual Japanese Food and Restaurant Expo. About 3,000 pre-registered for the expo, with 146 suppliers participating. Attendees were business owners, managers, buyers, and chefs representing various trades – restaurateurs, retailers, and wholesalers. There was a significant increase in the number of wholesalers and Thai business operators.

Atsuko Kanai, Mutual Trading’s executive vice president, talks about the challenges they navigated and still face today, what this year’s event had to offer, and the future of the food industry.

“Our clients know that we hold the show every year around fall,” Kanai begins. “Obviously, no one asked during the pandemic. But they started asking last year if we were going to have the event. However, it takes months for us and the suppliers to prepare for this so we need the reservation from them about six months prior to the expo. Additionally, Japan was very conservative; a lot of companies were not sending employees here because of health and safety concerns. And without our suppliers – many of whom are from Japan – we have no show or customers won’t have fun. We decided to hold it this year when we were certain about safety and we knew Japanese suppliers would come.”

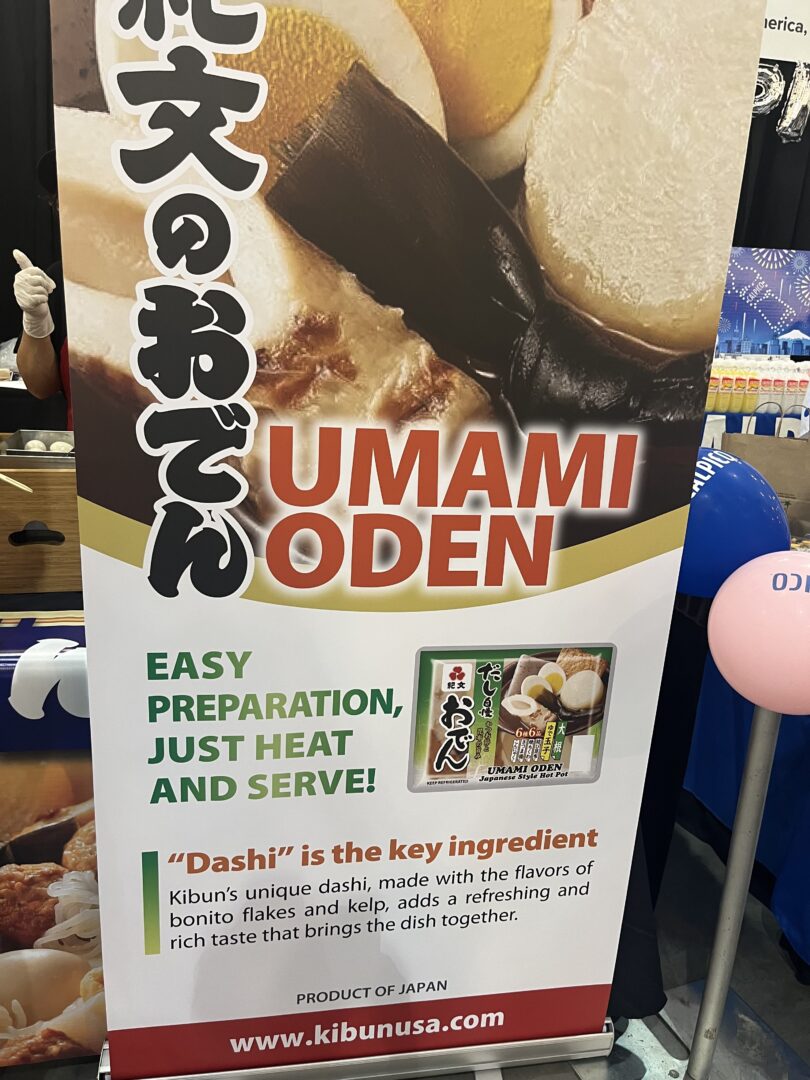

“Chefs want this show so we try to bring in things that they would appreciate,” clarifies Kanai. “There are 146 suppliers participating from Japan, China, Southeast Asia, Canada, Mexico, the U.S., and other places. They carry dry items and ingredients like tempura flour and rice; chilled, frozen, and super frozen grocery items like beef and other meats; a line of kitchenware for the chefs; alcohol like beer, wine, hard liquor, and so forth. The school that trains the chefs joins the show as well.”

“However, Japanese food isn’t just for the Japanese anymore – it’s for everyone,” Kanai points out. “So we have an obligation to grow the industry for our business and our customers’ business. We also believe that food is a gateway to cultural understanding, much the same way as sports, fashion, and the arts unify us and transcend wars and politics.”

Kanai has been with the company for several decades and has witnessed how people’s perception of Japanese food has advanced through the years. She recounts, “Thirty years ago, Americans who came to our booth would say, ‘I love Japanese food.’ And when I asked why, they would say, ‘Because it’s healthy and good for the mind.’ But recently, the answer I get the most is, ‘It’s fun.’ People who grew up during the depression and war wanted something bright and positive while those in their 20s and 30s experience a new flavor and it feeds into their knowledge. I’m looking forward to hearing what people say 30 years from now.”

The pandemic upended everyone’s life and altered what we thought of as normal day-to-day existence. The food business, in particular, was severely affected and Mutual Trading quickly reacted to mitigate the anxiety and pressure caused by the crisis.

“No one was able to go grocery shopping, especially the elderly. So we started a food delivery service,” states Kanai. “Depending on where the customers are, they would order online and, with a minimum order, we would deliver certain products to their home. People didn’t mind the large quantities because they were able to buy products that supermarkets don’t carry. We offered the service for a couple of years and discontinued it only this past spring.”

“On the restaurant and wholesale side, we couldn’t in good conscience send our reps on sales calls,” Kanai continues, “We asked them, though, to make sure they kept in touch with their customers – who were themselves going through hardship and were having to cut back service hours and staff – by Zoom or phone calls. All our suppliers in Japan were also worried because Mutual Trading wasn’t ordering from them. First of all, there was a supply chain breakdown. And when that stabilized, our Japanese suppliers were disgruntled that we didn’t buy more. But that’s because we couldn’t turn around to sell them to restaurants. The bigger issue was that they had lost faith in Mutual Trading. So we made sure we kept our suppliers’ confidence by sending out newsletters as a means of direct contact. We let them know that the slowdown wasn’t just in the Japanese restaurants but was also happening in the fast food and take-out business.”

Kanai says, “Having been through a pandemic, we’ve learned to be flexible. We can pivot when needed while ensuring our employees’ safety. We still face a few challenges post-pandemic. The first of which is less-trained staff, like chefs; they can’t learn on the cuff. So we’re teaching them to use items they don’t have to prepare from scratch when they cook. Some of the sauces will already have seven out of the ten ingredients and they will only need to add to the base. That eliminates the hard part, like making the dashi or umami.

“Another challenge is meeting the demands of customers on extreme price points. While some like turnkey volume-priced items, there are others who want to have a rare food experience like the omakase – $300 to $500 dinners. So we have to give something different for that market. We thought Kobe beef was hot but then we discovered that Miyazaki beef (the four-consecutive winner of the Wagyu Olympics Championship) was better. And now we’ve found another category of beef that’s even better. We constantly look for, and try to achieve something different to distinguish from the other.”

With that in mind, Mutual Trading brought in several new products and suppliers to this year’s show. They also shined a light on Japanese liquors and wines. Kanai explains, “We’re trying to start a trend showing that sake isn’t just a beverage – it should go with food. We’re pushing the gastronomic way of enjoying liquor like the Europeans do. Californians like to guzzle, as they do with beer. That’s fine too, but we’re striving to educate diners how to have a more pleasant meal. People are familiar with wine pairings, but wine is very different from sake. It’s not to say that it’s better or worse. We’re trying to compare the two and point out where the differences are and what’s good for one or the other.”

This year’s expo highlighted the four workshops presented by chefs, bartenders, and master sommeliers to achieve that goal.

The first workshop, called ‘Prestige in Every Pour: Indulge in the Mystery of Black Label Sake,’ featured three premium sakes and a demonstration on how they elevate an understanding of sake service, perfect food companions, and beyond.

Workshop 2 – ‘Taste the Craftsmanship: A Journey through Time and Flavor with Sokujo, Kimoto, and Yamahai’ – unveiled the artistry behind sake flavors shaped by diverse brewing methods and showed how to harmonize the three distinct brews with culinary pairings to create a sensory symphony.

The third workshop, whimsically named ‘AwaMORE Please! Unravel the Enchanting Flavors of Awamori, Tropical Okinawa’s Distilled Spirit,’ took participants on a tasting odyssey into Okinawan culture and a discovery of the perfect food companions.

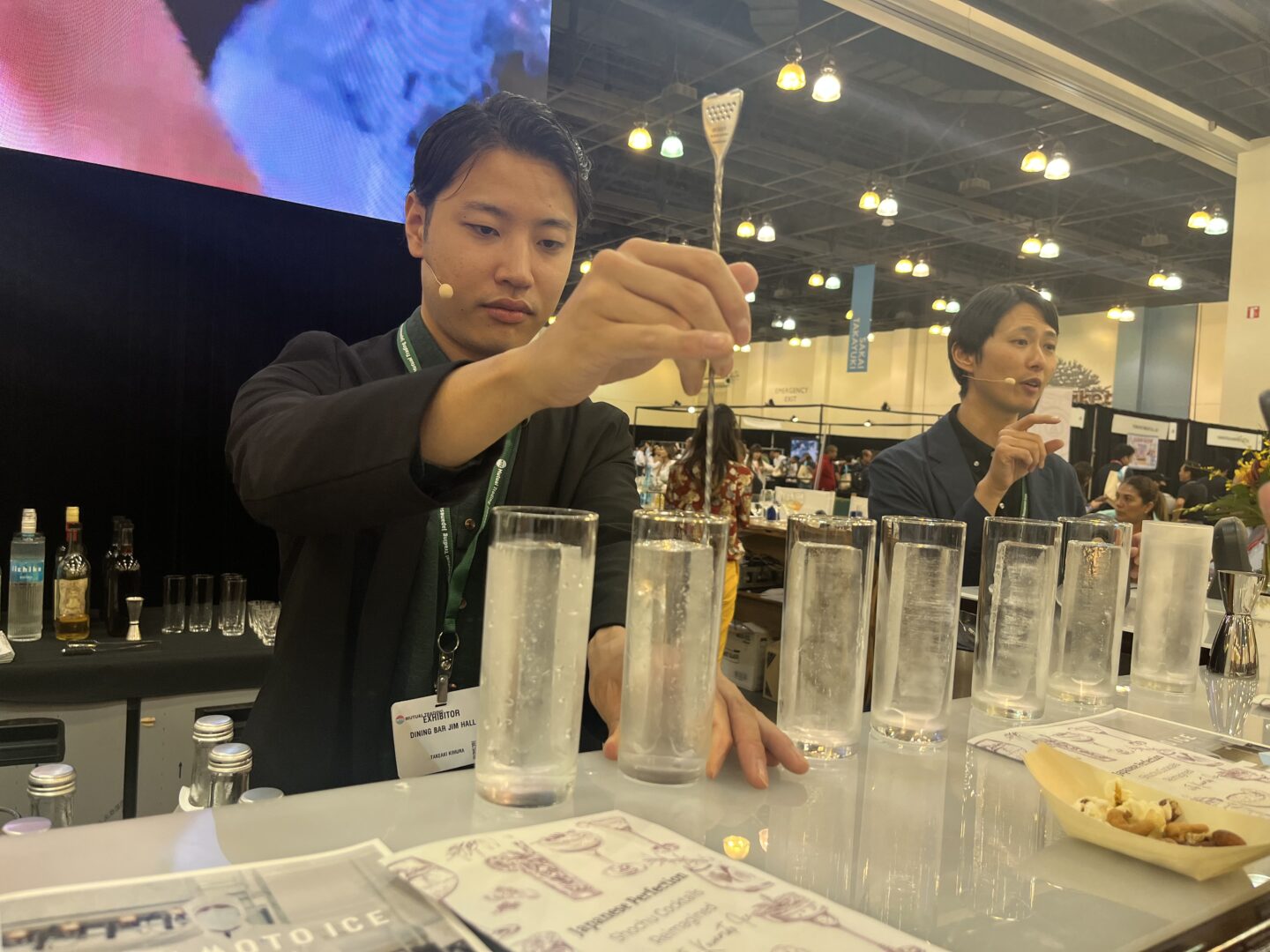

In Workshop 4: ‘Japanese Perfection: Shochu Cocktails Reimagined with Kuramoto Ice,’ Naoto Yonezawa, founder of Kuramoto Ice USA himself, served as translator for Takaeaki Kimura – manager and bartender of dining bar JIMHALL, in Kanazawa, Japan, and influential mixologist – who showed his signature cocktails blending rum, coffee, and vermouth.

Japanese cuisine has come a long way from its early introduction into the American dining culture. Going to a Japanese restaurant for lunch or dinner is now a common, everyday choice. Almost everyone is tech-savvy and is on social media posting photos of their meals. And that helps all restaurants, not just those serving Japanese food.

Kanai confirms, “On the surface, consumers today know a lot more than they did 50 or 30 years ago because of things they find online. Perhaps, and maybe more importantly, travel is the biggest factor in furthering the restaurant business. When people travel, it’s all about sightseeing, experiencing new places, and trying out food. People don’t just go to Japan to look at temples, bridges, and palaces; they want to eat. Them going abroad and coming back is feeding into our business.”

That said, the pandemic has left a trail of problems that continue to beset the Japanese food business – staff shortage. Those who used to work in restaurant service didn’t come back after Covid. It’s a statewide problem and not limited to Japanese restaurants. However bleak that might sound, Kanai believes that the future is sunny.

“Southern Californians are looking for different food experiences, and it isn’t exclusively Japanese food. The Michelin people keep skipping us, thinking that Northern California has the monopoly on exciting, innovative food. But the chefs are changing; I don’t see too many traditional Japanese food being successful. Nobu is a favorite among diners but it isn’t serving Japanese food, it’s fusion. And I think it’s happening with Chinese food too – the restaurants aren’t just Cantonese, or Taiwanese – chefs are modernizing their offerings and are creating the new wave.”

The Western San Gabriel Valley, Pasadena specifically, is a foodie heaven. It’s every gourmet’s paradise! There are, in fact, over 2,000 restaurants dotting the area, from Duarte to Alhambra – from fast food chains, to hole-in-the-wall mom-and-pop cafés, to Michelin-recognized restaurants – offering a global cuisine.

Eating places that cater to the taste of this largely Asian market are enjoying a booming business. Omakase is not just being offered in Japanese restaurants, but at American steakhouses as well. It wouldn’t be too far-fetched to imagine that chefs and restaurateurs could take their cue from the expo’s workshops and put on sake and food pairings as a mainstay on their menu. And that would take us on a new and extraordinary gastronomic journey.