For Asian Americans, who have been largely ignored by society, the events of the past three years that threw them headlong into the spotlight were too overwhelming to contemplate. Surely invisibility would have been preferable to being widely hated and reviled. While racial slurs and violence directed against Asians and Asian Americans didn’t happen only recently, the anti-Asian rhetoric and crimes that erupted during the pandemic were so alarming that they became the catalyst for movements, including Stop AAPI Hate.

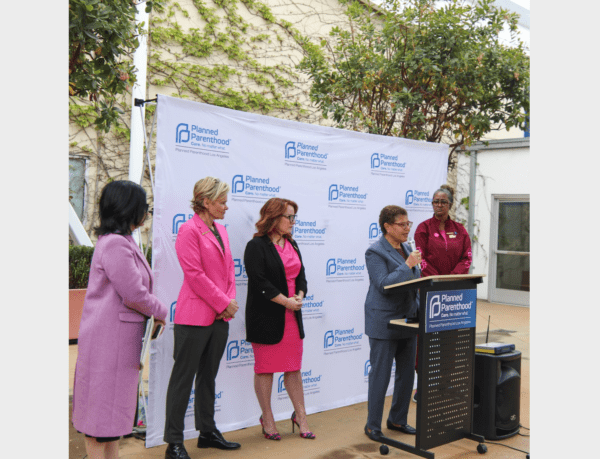

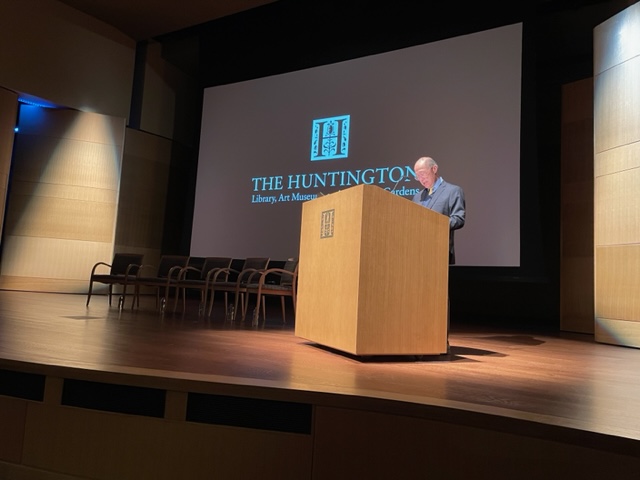

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino is at the very center of the Asian American community in the San Gabriel Valley. Its collections have grown and its programming has expanded to reflect the demographic change and the needs of the community it serves. On Saturday, March 4, 2023, it held a day-long symposium titled “Asian American Experiences in California: Past, Present and Future.”

Alice Tsay, Director of Special Projects and Institutional Planning, declared that this series of lectures was two years in the making. Indeed in the two years since The Huntington embarked on this series until it actually transpired, stories related to Asians have dominated headlines.

In his introduction and opening remarks, Simon K. C. Li, Huntington trustee, talked about the Monterey Park massacre on the eve of the Lunar New Year, and said, “Reaction among Asians who have witnessed racism is disbelief that we are capable of such violence. Another mass shooting perpetrated by the same man in Alhambra reinforced the thought. Still, it’s a reality — Asians in America live with a sense of vulnerability.”

Li then brought up two issues. The first involves the name Asian American — does it do a disservice in obscuring the wide diversity of the many Asians to reduce the knowledge and complexity that will otherwise lead to great understanding? He said in 1992 the terms Chinese American and Japanese American were much more commonly used. But it didn’t save Vincent Chin, the Chinese American beaten to death in Detroit by two bat-wielding white auto workers angry about the popularity of Japanese cars.

The other issue is about the role of representation in helping minority communities. Li said it’s a common complaint that we don’t see enough faces like ours in movies, on TV, or in government and politics in the news. But he contended that he’s seen plenty of representation for both Asian Americans and non-American Asians making their name in U.S. politics, in movies, and on television. And he wondered, “Do such talents, such contributions, such celebrity really redound to the ‘normalization’ of Asian communities in America?”

At the end of his remarks, Li asked the panelists to answer two questions and suggest new answers going forward for Asian Americans: “What does it mean to be American? Who has the right to wear that title and to share fully in the promise it implies?” (read Brianna Chu’s response article here)

The first panel — Historical Roots (pre-1965) — focused on the origins of Asian experience, and anti-Asian racism, in California, with presenters drawing extensively on The Huntington’s Pacific Rim collections.

Gordon Chang, whose talk ‘Beyond Promontory: Chinese Railroad Workers and the Rise of California,’ continues the story of the Chinaman as railroad builders and what happened to them after they finished the transcontinental railways. He touched on the construction of the Tehachapi Loop in 1874.

An interesting revelation was when Chang debunked the myth that the railroad workers were docile. “In March 1875, the entire workforce tunneling in the Tehachapis went on strike for higher wages just as they did in 1867. They took advantage of the monopoly they had on railroad labor and demanded for improved working conditions.”

Naomi Hirahara’s presentation was “Torri Gate Welcoming Empire: Japanese Immigrant and Nisei Cultural Workers and Pasadena Landscape and Life.” She spoke about her lived experience as a Japanese American in Pasadena. Her father, Sam Hirahara, was a gardener. She said, “Many Japanese American men after World War II were gardeners. A lot of men who were released from the detention camps found it was easy to come over — all they had to do was push a lawn mower and they were in business.”

She also talked about George Turner Marsh, a businessman from Australia who had spent several years in Japan and learned the language. “He went to San Francisco and opened an Asian arts business in the late 1800s. He installed a Japanese house in the 1893 Chicago World Fair in the area that the Japanese government funded, which one of the architectural partners of the firm Greene & Greene saw. Frank Lloyd Wright also saw it as a little boy. This was the introduction to a Japanese aesthetic that perhaps made a lasting impact among American architects.”

Jean Chen Ho talked about the Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre of 1871, the culmination of anti-Chinese sentiment leading to racially motivated violence and for which a memorial is being built.

“According to stories, in the late afternoon of October 24, 1871 a gunfire broke out between two Chinese men from rival tongs on Calle de los Negros, now Los Angeles Street, feuding over a young woman,” Ho began. A white rancher was caught in the crossfire that caused his death. A vigilante mob then gathered to exact revenge for the slain Anglo man and went on to murder 17 Chinese men and one 15-year old boy. The mob also raided a number Chinese businesses of goods and cash, and destroyed property by fire. Newspaper accounts by L.A.’s elite often demonized ‘ruffian and disreputable class’ for the massacre. But what combined these two social sets on that night was white vigilantism that enabled the massacre. This incident put the blame back on the Chinese for the violence they suffered.”

An account of this massacre that night was written 50 years later in his memoir by Robert Maclay Widney who witnessed what happened and was later the presiding judge during the trial of the rioters. But Ho questioned the credibility of his story where he painted himself a hero, “Where do we place someone like Robert Maclay Widney who had the power to narrate his own story and have its social and material integrity preserved? What about the distorted, destroyed, or otherwise absent narratives from the victims of the massacre as well as those who survived that night of violence? The work that I’m taking up now is to reckon with the speculative possibility that Asian American lives have been previously only seen visible at the very moment they were suddenly extinguished by violence. My next project — a novel — now requires the intellectual and emotional capaciousness to imagine all that cannot be verified by the archive in order to tell a story about lives that exceed the archive in their sublime and impossible beauty.”

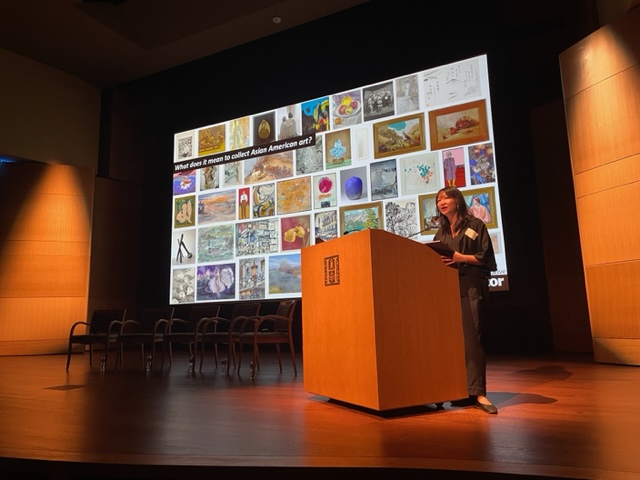

Marci Kwon’s presentation centered on the Asian American Art Initiative at Stanford University, an effort to collect and preserve histories and works of Asian American artists which reflect some of the subjects discussed by the other panelists. It’s a joint effort between the Canter Art Center and Stanford Library’s Special Collections which started in 2016. It came about because when she was trying to put together a syllabus for an Asian American Art history, she couldn’t find one. Thus her challenge was to collect 1,000 pieces of artwork by AAPI artists by 2026.

The second session – Shaping the Present – covered the period from 1965 to the present.

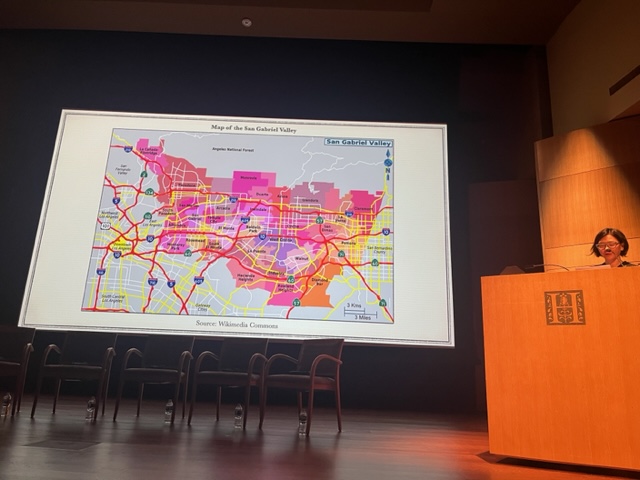

Wendy Cheng, called her talk “Assimilating into Difference: Multiethnic and Multiracial Histories of the San Gabriel Valley.” As Li did, she began her presentation with the Monterey Park mass shooting, “In the days after the shooting, Monterey Park was listed as an Asian American hub. It was a place of possibility for Asian immigrants to make lives and build community. Indeed in 1990, it became the first majority Asian city in the Continental United States; its population is 65% Asian today. But what this characterization can sometimes gloss over, is the incredible multi-ethnic and multi-racial richness of Monterey Park’s history and present — which came about through multiple generations of shared history of struggle and place-making.”

“In the near 70 interviews I conducted for my book ‘The Changs Next Door to the Diazes’ between 2006 to 2012, I found that those who grew up in Monterey Park and the western San Gabriel Valley developed a distinct regional consciousness about race,” disclosed Cheng. “They usually understood the particulars of each other’s identity. This region’s distinction as an Asian American place is one of its legacies — a home for immigrants and for those who are historically excluded or vilified elsewhere by those who don’t look exactly like them.”

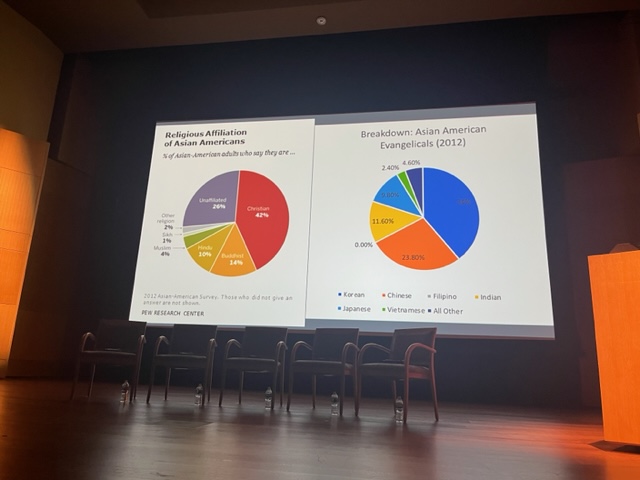

Jane Hong spoke about “Asian American Evangelicals and Southern California Histories” and how they became an important voting bloc for the Republican Party. She attributed this to a couple of developments: the first was the diversification in U.S. population that resulted from the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Japanese Americans made up the majority of Asian Americans for much of the 20th century; Chinese Americans became the most populous by the 1980s; Filipino Americans became the second largest Asian American group in 1990; and, very recently, Indian Americans surpassed the Filipino Americans as the second largest Asian American population.

The second development was the marriage between white Evangelicals and the Republican Party. This can be traced to the Moral Majority, a political lobbying group formed in 1979 between Jerry Falwell Senior, the founder and president of Liberty University, and Ronald Reagan. They joined forces around a shared set of issues — opposing abortion, traditional family and marriage defined as between a man and woman, etc. And their influence grew within the Republican Party in the 1980s.

“Late 1960s and 1970s phenomenon Jesus (Free) Movement were largely young, white Americans,” Hong explained. “At the same time, Movement Activist was inspired by Asian American movement whose major tenet is ‘there’s strength in solidarity.’ So instead of calling themselves Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, it was a political act to call yourself Asian American to denote your belief, community, and shared interest. So this is what it means to be Asian American and Christian — integrating racial and individual identity.”

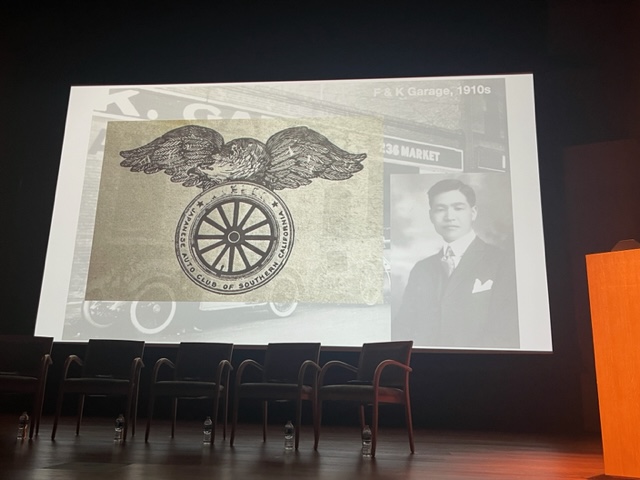

Oliver Wang’s topic was “The Nisei Week Cruise: Japanese American Car Culture in the 1970s and 80s.”

“So much of our car history has been written by white men so the Nikkei community has been largely forgotten or overlooked,” stated Wang. “A major goal of the exhibit is to write the Nikkei Community back into the stories and histories about how cars have transformed the cultural, economic, and social landscape of the Southland.”

“Nisei Week began in Little Tokyo in 1934 as a way to encourage cultural pride in community economic development by an emergent second generation of Japanese Americans — the Nisei — who wanted to stake out a space for themselves within a community that up to that point had been largely dominated by their Nikkei parents and their generation,” continued Wang. “It quickly grew to become an annual celebration of the Japanese American community and further anchored Little Tokyo as the center of the Nikkei community in Southern California.”

Wang reported that Nisei Week cruise began to form in the early 1970s. “By the 1980s Nisei Week Cruise became the ‘king of cruises’ and continued to grow in popularity for the next 15 years until the summer of 1988 when it was shut down. But it left a lasting impression — for the people who grew up at that time, cruise was fundamentally a social experience that connected young people with one another. To attend the cruise was to participate in a cultural experience that helped define what it meant to be young and Japanese American for an entire generation.”

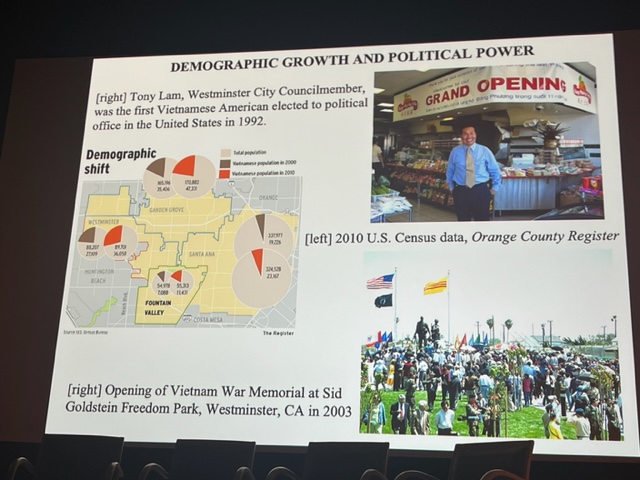

Linda Trinh Vo talked about the Vietnamese population in Orange County. She stated, “I titled my talk ‘Crafting Community’ because ‘crafting’ is purposeful – it needed a skill not just ad hoc. There’s an assumption that America rescued the Vietnamese refugees and other Southeast Asians. There’s a whole other discussion we can have about America and their intervention in the war in Vietnam that led to our displacement and then led to our migration or forced migration as asylum seekers and refugees. But our argument is that we saved ourselves. We had social agency — we had to figure out a way to survive, to get out of Vietnam and get resettled in the U.S. At times, we’re looked at as passive victims rather than seen as social agents helping ourselves.

“Today, the Vietnamese population is the largest of Asians in Orange County and also the largest population outside of Vietnam,” declared Vo. “Pre-1975 the only ones here were war or military brides, international students, and military personnel training during the Vietnam War. When the Vietnam War ended, about 120 of them were settled in Camp Pendleton, one of four U.S. camps where refugees settled. But they needed some place to live permanently so they had to find sponsors. Individuals, charities, religious organizations helped to sponsor and settle them in the city of Westminster (and later expanded to Garden Grove) which is today’s Little Saigon.”

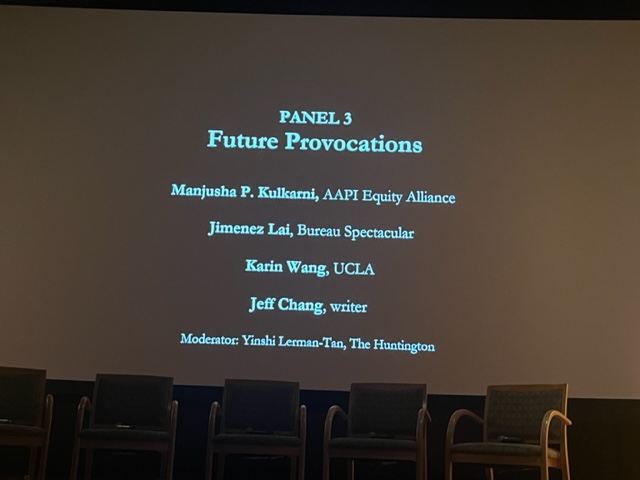

The third session – Future Provocations – envisaged the future of Asian Americans from the perspective of the panelists’ field of expertise.

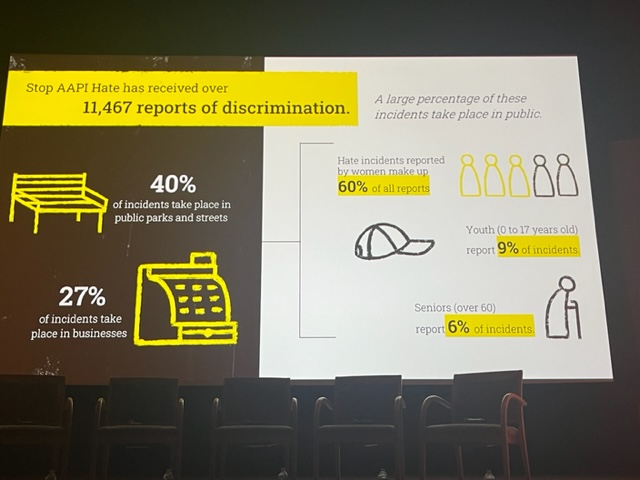

Manjusha P. Kulkarni‘s presentation was “Resistance and Resilience: Asian Americans’ Response to Hate.” She disclosed that since the beginning of the pandemic, Stop AAPI Hate received over 11,467 reports of discrimination. She said, “Policies drive much of the hate — mass deportation of Southeast Asians, programs like the China initiative, the 911 surveillance and profiling of South Asians. What that has led to is the blame game — one in five reported incidents include this kind of scapegoating, like public health which we saw during the bubonic plague where Chinese Americans were blamed for the disease. National security was blamed for the Japanese incarceration and 911 profiling. And economic insecurity and anxiety was the cause of the horrible beating of Vincent Chin.”

“As populations are growing, we begin to see ourselves as racialized,” continued Kulkarni. “Civil Rights leader and scholar Lani Guinier wrote about the social ladder when whiteness is at the top and blackness at the bottom. So where does that put Asian Americans in terms of the outsider framing, idea of perpetual foreigner.’ So where are you really from?’ are the questions we get even when we’re third, fourth, and fifth generation. And that leads to questions of loyalty — are we actually Americans?”

Kulkarni then discussed civic engagement, “Since 2020, we are more enthusiastic about voting than we ever had; we see that we play a role in the margin of victory. So it’s absolutely critical that we vote; and engage civically — write to your congressperson, go to meetings at city hall, and run for office. We need more representation across our land if we are to have a powerful voice. I want to leave you with this quote from Grace Lee Boggs, ‘You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.’”

Artist Jimenez Lai showed some photos of the work he’s done over the years. He represented Taiwan at the Venice Biennalle; his works have been displayed at museums and public events, including Coachella. One of his installations in front of City Hall, at Grand Park, is a collaboration with a musician and they conceived a structure like an oversized instrument. They embedded an amplifier so people could whisper their sorrows into it which then get distorted into nonsense — a confession booth of sorts.

Karin Wang spoke about “Asian Americans: Racialization & Privilege.” She began with a slide on Anti-Asian Hate which mirrored Kulkarni’s visual on the number of hate incidents. “What’s interesting is that at the same time that we were being racialized and targeted for violence and hate, Asian Americans are also occupying important spaces of privilege in two professions — Law and Medicine,” she declared. “We need to recognize where we have power and privilege. Lawyers are among the most powerful members of our society — not just lawyer lawyers, but judges, elected officials, people running government agencies.”

Wang added, “There are a lot of stereotypes about Asians, one of them being that they are mostly in Medicine. And it is another sector that’s economically and socially advantaged in our society. There are improvements in the number of people of color in medicine on the national level but the majority of doctors are white; the next largest group is Asian and Pacific Islanders; Latinos and blacks are two populations that are underrepresented. It is becoming more racially diverse over time, although it is actually Asian Americans who are taking up a lot of that space.”

“Asian Americans are obviously not white and have never been viewed as white. Yet, we do have some privilege here as a community. So what is the provocation for the future as we move forward as Asian Americans? How are we going to think of ourselves in terms of where we fit in the American racial landscape? What are we going to do to use our positions of privilege in these places where we have it, and advance racial justice and equity not just for Asian Americans but for other communities of color as well,” Wang asked in conclusion.

The last speaker was Jeff Chang, who started his presentation by saying, “I was provoked by what Simon Li asked us to examine. The first: what is the desirability of being called Asian American especially given the anti-Asian violence we’re living through? And, second, the role of representation. We know that there is representation, but we also recognize that we are nowhere near what the culture industry calls for, which is to create narrative plenitude – the diversity of stories out there.”

“Can we create a narrative of Asian American that can take us to the next 50 years? Chang asked. “Narrative plenitude doesn’t just seem like a call to the white-dominated culture industries and social institutions. But it seems also for us to make better sense of the full diversity of our stories. But at the same time, violence is bringing us all back together. But it’s not that the violence makes us all Chinese, the violence makes us all Asian American. So when we say ‘Stop Asian hate, stop anti-Asian violence!’ we can call this a negative narrative. We’re saying ‘Stop, no more of this!’ But this narrative also has its limits. There’s a danger that we actually lose people to the fears. Is there a positive narrative of Asian American that can bring us together?”

Chang ended his presentation by yet posing these questions: “How do we form this new narrative that’s not just saying ‘No,’ but what can we all say ‘Yes’ to? How do we recognize the harms being perpetrated against us and not re-harm others because of that? But how does that help us think about what we might move to that can lift us all up together?”

This symposium resonated deeply with me. As an Asian American, I related with the experiences some of the panelists described. I’ve lived here for 41 years and, every once in a while, I’m still asked where I’m from. I usually respond “I’m from Pasadena but originally from the Philippines.” Sometimes, though, I turn what might otherwise be an awkward exchange into a subtle teachable moment about the Philippines and Filipinos, and our historical ties to the United States.

As to Simon Li’s parting questions, there are as many answers as there are perspectives. And here’s mine: those of us who aren’t Americans by birthright but who legally immigrated to this country to build better futures also have the right to be called Americans. Most of us rose above our circumstances not in spite of being ‘foreigners’ but because of it. Most of us were born and raised in places of poverty and hardship and we were taught that education and industry were the means to success.

Because we didn’t come from places of wealth and abundance, we didn’t take for granted the opportunities that were available to us, as most immigrant accounts attest to. The possibilities became seemingly limitless and within reach because we were willing to work hard for them. Failure wasn’t an option — we wanted to ensure that our children didn’t go through the struggles we had to endure.

But being American comes with responsibility. We have to give back to the country we now call home by engaging with our community and actively seeking out how we can contribute to society. In areas where we have influence, we have to advocate for all people of color and use our voices to speak for those who can’t. At the very least, sharing our stories might help others understand that while we don’t look like them, we have similar hopes and dreams, and are striving for the same happy outcomes.