The effects of climate change have doubled the chance of a catastrophic storm and devastating flood like the one that ravaged the state in 1862, with a similar event likely to displace millions of people and leave areas like Los Angeles under water, according to a UCLA study released Friday.

“In the future scenario, the storm sequence is bigger in almost every respect,” Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientist and co-author of the paper published in the journal Science Advances, said in a statement. “There’s more rain overall, more intense rainfall on an hourly basis and stronger wind.”

Researchers studying a so-called “ArkStorm” scenario — a reference to a flood of “biblical” proportions — found that a modern-day storm mirroring the 30-day deluge of rain that occurred in 1862 would generate 200% to 400% more runoff in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The increase is due to more precipitation falling overall, and more of it falling in the form of rain, rather than snow, researchers said.

“On 10,000-foot peaks, which are still somewhat below freezing even with warming, you get 20-foot-plus snow accumulations,” Swain said. “But once you get down to South Lake Tahoe level and lower in elevation, it’s all rain. There would be much more runoff.”

According to researchers, if such a storm event were to occur, the dramatic increase in precipitation and runoff would cause “devastating landslides and debris flows.”

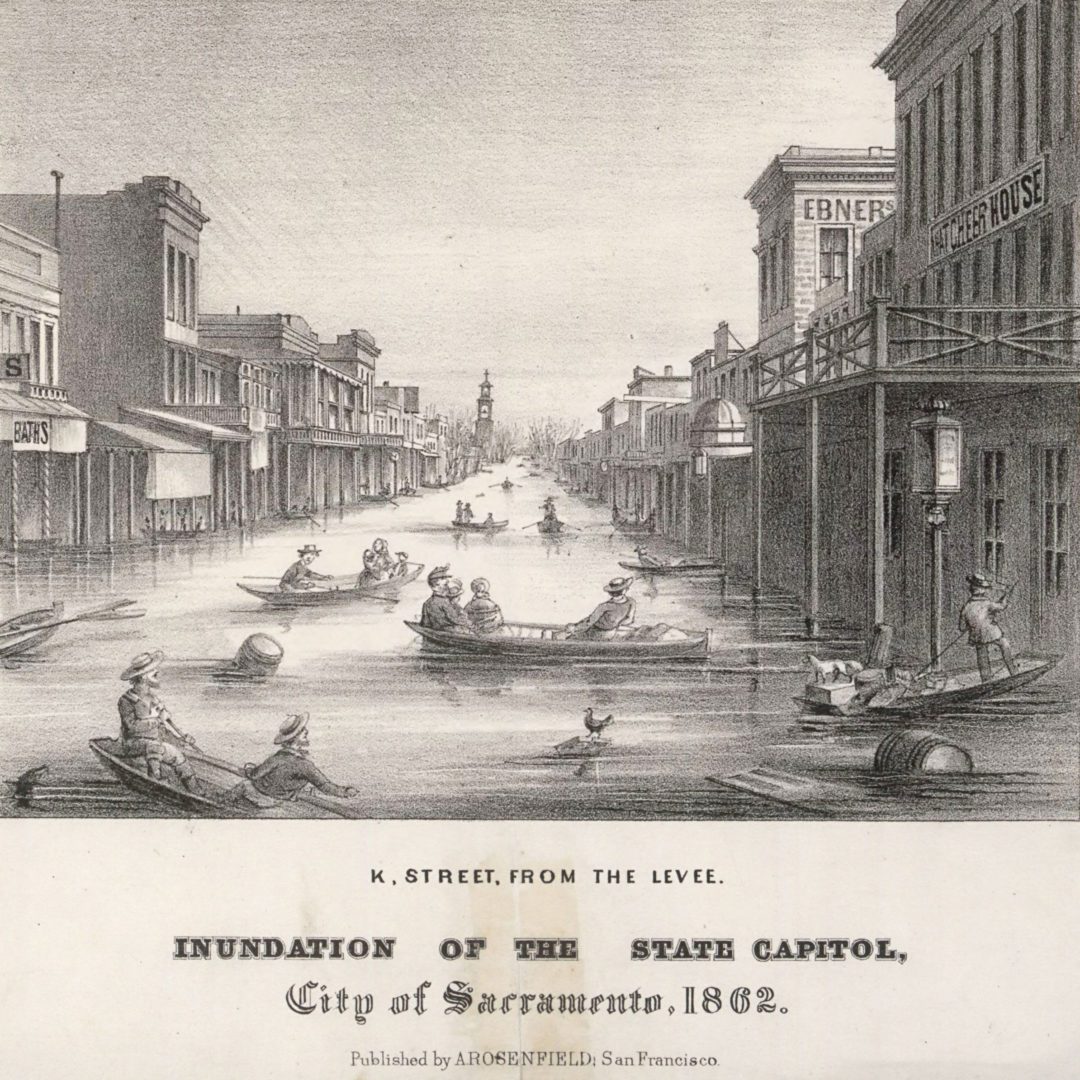

Researchers noted that the Great Flood of 1862, occurring before the development of any flood-control infrastructure, led to flood waters that were 300 miles long and 60 miles wide.

Even with modern flood-control measures, a similar event Friday would leave parts of cities such as Sacramento, Stockton, Fresno and Los Angeles “under water,” causing an estimated $1 trillion in damages.

Such a storm would also lead to the displacement of 5 million to 10 million people due to flooding, and researchers noted it would likely be impossible to fully evacuate the millions of impacted people, even with weeks of notice of the pending storm.

Predicting when such a mega-storm could occur is an inexact science, but researchers said similar storms traditionally occurred every 100 to 200 years previously — and before the impacts of climate change.

“Modeling extreme weather behavior is crucial to helping all communities understand flood risk even during periods of drought like the one we’re experiencing right now,” Karla Nemeth, director of the Califiornia Department of Water Resources, which contributed funding for the study, said in a statement.

“The department will use this report to identify the risks, seek resources, support the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan, and help educate all Californians so we can understand the risk of flooding in our communities and be prepared.”

Researchers pointed out that an “ArkStorm” flood is also known as “the Other Big One,” referencing the term for an anticipated major earthquake. But an “ArkStorm” scenario “would lead to catastrophe across a much larger area.”

“Every major population center in California would get hit at once, probably parts of Nevada and other adjacent states, too,” Swain said.