(Editor’s note): This is the second part of a series that examines the “Empty Bleachers” of high school sports during 2020 at the peak of COVID-19. This story explores how coaches navigated the chaos with no physical practices or games, all while having no answers that they could provide their players about the future. To check out the first story titled “Empty Bleachers: A series on the 2020 experience of local high school athletics,” click here.

. . .

Lucinda Buchan has been the head coach of the Alverno Heights Academy softball program for 13 years. Throughout her professional life, she has faced obstacles and responded with impressive strides to accomplish incredible feats.

After receiving her bachelor’s degree at Ball State University in Indiana — where she was a softball star for the Cardinals — she attended UCLA and earned her master’s in secondary education.

Two years later, she earned her first full-time job as the president of the Apex Plastering Company, a business that has worked as a subcontractor in construction throughout the San Gabriel Valley for 50 years. She has worked for the company ever since.

Yet, only four years after earning the role she became the head coach at Alverno Heights, where she has helped bring the Jaguars a level of success that the program had never experienced prior.

And somehow, throughout her decade-plus-long tenure as president of a highly successful company while simultaneously leading a group of young women to consistent California Interscholastic Federation-Southern Section (CIF-SS) postseason appearances — not to mention being the mother of her two young children — she has had this amazing ability to remain composed.

Pulling Through Covid Chaos

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, however, a difficult question lingered inside of her head for weeks: can I possibly stay composed through this?

“I just had to find a way to take it all in stride,” she said. “I had a kid that needed to be homeschooled at the time, which was already very difficult. So softball needed to take a backseat, and I didn’t get to hear or talk to the girls all that much during the hiatus. Which was hard, cause before the pandemic hit we were in the middle of a strong season. And suddenly it just stopped.”

This, of course, was a universal issue. Everyone’s agenda stopped. Passions needed to be thrown out the window in order to maintain public safety. Yet, that pressure reaches an insurmountable level when there are developing teenagers wanting — and oftentimes needing — a coach’s guidance.

Left Without Answers

“I was just as surprised as the rest of my team when Covid hit and ended our season. And it was a situation where players were texting and calling me looking for answers, but I didn’t have any,” said Monrovia High baseball head coach Brad Blackmore, whose team only played eight games in 2020 (the regular amount per season is roughly 25 games).

The theme of not having answers persisted for nearly an entire year, and very early on people in high school athletics were essentially asked to take a test without studying. Coaches began guessing for the right answer, hoping to keep players engaged despite needing to adapt to a remote experience.

Fall sports maintained a level of hope for a 2020 season during the summer. The science behind the virus was still largely unknown on the transmission of Covid and its long-lasting health effects.

Sports like football and volleyball still needed to get teams prepared for a potential return in the fall of 2020. Not being able to meet on campus and use campus facilities in July and August meant coaches needed to construct their workouts through Zoom.

Engagement Challenge

Engagement for several students became extinct. At-home setups for weight training made it difficult for coaches to regulate what was happening. Coaches needed to get creative to make it work.

“We had four guys who played in the NFL jump onto Zoom calls to keep the kids motivated,” said La Salle College Prep football head coach Ben Buys. “The competitive nature also helped bring in some motivation. Push-up contests and sit-up contests, stuff like that. It definitely wasn’t the easiest thing to monitor.”

This reality, which lasted throughout the fall semester, eventually vanished with programs being cleared to begin training on campus again that next spring. But things still weren’t quite the same, and the answer to when teams could begin play again became even more unclear heading into 2021.

Attempting to Restart

Coaches were in constant communication with their school’s administrators to stay updated on what protocols the CIF would follow. While outdoor practices were permitted, the question of if a group of players can play against another group of players in a different region complicated an official return to play.

What made these issues even more tricky is that nearly every decision made by LA County and the CIF didn’t lead to a bigger answer. When it was announced that the CIF-SS eliminated its playoff format for fall sports in January 2021, that didn’t necessarily mean that fall sports would no longer have a regular season. Additionally, when that decision was made, there wasn’t an update on whether winter and spring programs could participate in a season simultaneous with fall programs.

Even when there was strong communication between coaches and their administration, answers were nowhere to be found.

“I felt through that entire process I had a great relationship with our administration about where we were at realistically. But when I was talking with them and having Zoom meetings with newspapers and other coaches, all the updates were nothing but negatives,” Blackmore said.

I tried my best to keep the kids informed through everything, but it got harder and harder the more it went on. Just to tell them constantly that their season was being pushed back more and more; it definitely took a toll on me.”

Love Lost

That constant negativity was even more difficult to accept for several coaches since their comfort in times of frustration was their job — the sport they love to teach. And while they were technically coaching their players in person again, the atmosphere left everyone involved feeling on edge.

Every team who practiced at this time was required to split up into smaller groups, which were completely exclusive. Masks and social distancing needed to occur in order for practices to take place. Whenever a player touched something during practice, that item would be sanitized immediately afterward.

The social distancing restrictions brought an end to the normal interactions that teams would have in locker rooms and practices. More importantly, it eliminated the personal moments in which coaches and players could connect as individuals.

“That is probably the hardest part,” said Buys. “I’ve only been here since 2019, and that first year I would have six or seven guys come into my office and eat lunch; talk football and life and goals for the season. That is one of the most enriching parts about coaching. Having my office be like a rotating door of kids and guiding them. That part had to stop my second year.”

Adapting To Uncharted Times

Adult coaches, who have been building these connections for their entire professional lives, were required to do their jobs without the part that fulfills them the most. And for the kids who were without personal guidance from a figure that some looked up to the most, it affected their psyche far more. Coaches needed to realize that and adapt.

“You could just see how much that distance was affecting them. I don’t work with the school outside of coaching, so I didn’t get to communicate with them as much as I normally would have. But when I did I could hear it in a lot of their voices,” Buchan said.

“Being at home away from their friends was very emotionally draining for some of my girls. They were hurting academically, and there’s only so much adults can do to get them out of that. They need that space to thrive.”

A collective sigh of relief was felt on Feb. 26, 2021, when Governor Gavin Newsom allowed outdoor, high-contact sports to continue on with a season. However, the announcement of a season was only a path; programs still needed to find a way to clear through it.

Stumbling Start

One of the biggest challenges at this time that was facing individual schools was the fact that many sports were now available to begin simultaneously. There, of course, was a sense of gratitude on many campuses during that time of revival, but the initial phases of returning ended up being a logistical, and predictable, nightmare.

Teams were being forced to share fields and courts. For instance, baseball teams allowing football teams to use their outfield for Oklahoma drills while they take ground balls in the infield. Basketball programs brought in volleyball teams to salt and pepper on the sidelines while they scrimmaged on the court.

“Everything was like a mad dash when things started coming back,” said Blackmore. “The season needed to be cut down to like nine weeks when we normally have about 10 to 12 weeks. And with the lack of space we had, I needed to cut my program from three levels to two and send the freshman straight to JV [junior varsity] in order to make room for other teams.”

Hurdles Took A Back Seat To Play

Nevertheless, Blackmore directly followed that sentiment by saying this: “But who cares, right? We were just so excited to be out there doing something.”

Adaptability to a difficult situation is far easier to respond to when compared to the loneliness that plagued 2020. Coaches and athletes alike were simply ecstatic to be playing again. There was still a seemingly insurmountable number of questions remaining when play was revived, but the answers didn’t seem to matter after the players were finally able to step on the field again.

“Part of being a coach is that when you have a bad day, you know you’ll eventually be able to get on the field and be with your team. But for a while there, we didn’t have that. So when that came back, it was just a game-changer for me,” Buys said. “Coming back after everything that happened really gave us a different hunger. We realized it could be taken from us at any moment.”

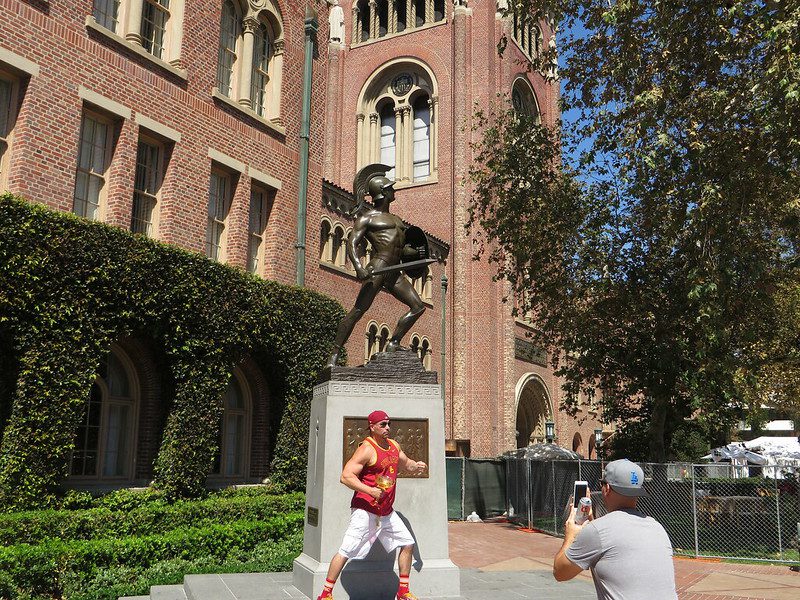

Ben Buys entered La Salle with a team who was 0-10 in 2018 and made them a playoff contender his first year before the pandemic hit. When play returned in March 2021, the team won three of their four league matchups. That was mainly due to the connection of quarterback Richard Munoz and receiver Marcus Powe, who led the team with 11 touchdown receptions.

Munoz won the Del Rey League Offensive MVP award that season and Powe committed in the spring to the University of San Diego’s football program.

Winning Ways Return

Blackmore has coached at Monrovia High for 33 years. He believed the squad that took the field during the season that was cut short was the most complete roster he’d ever coached. Yet, the sudden stoppage of play didn’t seem to affect the squad heading into the 2021 season, where the team accumulated a 21-4 record and won the Rio Hondo League title for the fourth time in seven seasons.

As for Buchan, was she able to overcome that concern and remain composed once the girls took the field?

Not only was she capable of doing just that, but Buchan and the Jaguars responded with one of the squad’s most memorable seasons to date. An emotional and exciting win against their rivals in the Sacred Heart of Jesus High School located in Lincoln Heights was a teaser to what the team would eventually become. Two months later, they played in a hard-fought defeat to Santa Monica Catholic — who was a Division 3 Champion the year prior — in the CIF-SS semi-finals. It was the furthest Buchan had ever taken her team in a postseason bracket.

“The ending was, in the moment, a disappointment. In that semi-finals, we lost in the seventh inning, and it was a game I think we should have won. But just being there, and the journey we took to get there, was so enjoyable,” Buchan said. “That group had such a good energy and spirit about them. And I think coming together after so long played a big part in that.”

‘Lost Year’ — A Life Lesson

That indescribable thing that makes coaches so valuable for students needed to be amplified even further in 2020 — what was described multiple times during these interviews as the “lost year.”

Players were quickly losing interest. Athletic directors didn’t have answers. Parents were expressing their daily frustration unlike ever before. The boulder was teetering off the edge of the mountain, but coaches wouldn’t allow it to hit the ground.

And while maintaining balance was never easy, the admiration for their players, and their love for their sport, was just enough to keep them fighting back.

Looking back months later, Buys, Blackmore and Buchan collectively agreed – it was certainly worth the wait.