Even those who can’t name the countries that comprise Southeast Asia know Bali – one of the islands in the Indonesian archipelago. Tourists flock there lured by the island’s pristine beaches, beautiful sights, and tropical weather. They bring back a few souvenirs from their holiday and, perhaps, a painting created by a local artist. These paintings became popularly called ‘tourist art,’ named so because they appeal to western visitors.

The emergence of this new style which veered away from Balinese traditional pigment on cloth is the focus of an exhibition at USC Pacific Asia Museum (USC PAM). Titled ‘Bali: Agency and Power in Southeast Asia,’ currently on view through June 12, 2022, the show features paintings collected by Bali cultural anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead during their fieldwork on the island from 1936 to 1939.

During a walkthrough of the exhibition, Rebecca Hall, USC PAM’s Senior Curator, talks about how the exhibition came about. “I learned that Dr. Robert Lemelson, an anthropologist, collector, and documentary filmmaker who lives in Los Angeles, has the collection of the Bateson and Mead paintings and he was interested in making these accessible to scholars and museums. We met in late 2019 and I had planned on having the exhibition a year later, but the pandemic started so we had to postpone the show. As disappointing as it was, that helped me think through how to present these materials because they’re unusual. It’s not just an exhibition about Bali but about this specific moment in time and the paintings that were created then.”

“There are 845 paintings and we’re showing 54 of them in this exhibition,” Hall reveals. “It’s exciting to be able to exhibit them for the first time in conjunction with the Balinese artwork and objects in USC PAM’s collection. There are two components that anchor the exhibition – classical Balinese objects that were made for use in Bali for Balinese audiences and the paintings from this moment in time when artists were starting to create artworks for outsiders. They’re two very different collections which have never before been shown to the public.”

Explains Hall, “Bali is one of the most famous places in Southeast Asia; the tourism industry has been a prominent part of Bali for a hundred years. And these paintings play an important role in understanding how the Balinese have adapted the artmaking that they do for outsiders to understand.”

To help orient people, the exhibition starts with a map showing the different cities in Bali. Visitors will very shortly come upon a wooden sculpture of Vishnu riding on his eagle Garuda, which was donated to the museum in 2020. Carved out of wood and brightly painted in pigment with gold leaf, Hall says it would have been in a temple or palace compound. It is a grand and dynamic Hindu image that people expect to see and makes for a very apt way to welcome us into the exhibition.

We then enter the first main gallery. Hall explains, “I designed this space with the idea of illustrating Balinese art and culture in an in-depth way to people who have no knowledge of and not necessarily familiar with the aesthetics of Bali and visual Balinese culture. Except for two items, everything on display here is from the USC PAM collection. One of the first objects we found was this umbilical cord holder. I’ve never seen one before – it’s really strange and unusual. In many cultures people are very protective of it because it’s this moment of life and it has power; they wrap it carefully and they wear it like an amulet around their neck. So I did some research and found out there’s one island in Bali where they put umbilical cords in containers and hang them from trees. I thought it was a good place to start because it’s the beginning of life.”

This part of the exhibition, according to Hall, is about how the Balinese understand the beginning of life, time, and the cycle of life – which is very different from the Chinese and Indian understanding. To them rice and life are synonymous. Hence, their calendar and way of life are directly tied to the cycle of rice production and the sequence in which both humans and rice rise from the ground, flourish, then wither, die, and return to the sky before circling back to Earth to begin again. Humans and rice are intertwined in Balinese culture and visual arts, informing the rituals and festivals that honor the beings of the underworld (bhuta kala), the earth (human), and the realm of the gods (Dewa). Artists and residents focus their creativity into ceremonial offerings (banten) and works of art, music, and dance performances to maintain balance.

The traditional Balinese calendar, called the pakuwon, is a 210-day calendar that is more like a cycle than a calendar year, corresponding to the precise amount of time rice takes to mature. The pakuwon is the main organizer of ritual time in Bali; it is the system of reference when planning any event of significance, including offering days, temple or house construction, weddings, cremations, and carving of sacred objects.

A secondary calendar system in Bali is the saka, derived from the Indian Hindu calendar. It is tied to the lunar cycle, with a strict system for understanding historical time. Both calendars have unique units of time that require close understanding of sacred numbers, particular deities and their attributes, elements of nature, mountains, and more.

There are several different objects in this gallery and Hall connects them by explaining how they’re used. We see a storage box for jewelry and important items and on the same display table is an architectural column. The objects are very different but they have a shared aesthetic – the elaborate carving on wood.

In another area, there are masks and items Balinese use for their performances. Hall explains that Bali is a Hindu island with a complex cosmology that manifests in a diverse cast of beings depicted in visual and performing arts. Some are characters from popular Hindu narratives that originated in India, including the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Others are drawn from local Balinese stories and beliefs about nature and ancestors.

Hall further expounds that the importance of narratives in Balinese art and worldview cannot be overstated and can be seen throughout the art and architecture of the island. Numerous characters of opposing forces, such as the human and the mystical, the devilish and the benign, the noble and the peasant, the serious and the lighthearted, are all portrayed. The different faces of the characters – be they gruesome, threatening, peaceful, or elegant – serve to reinforce the Balinese understanding that the universe is constructed from opposing forces. They believe that to survive, a balance must be met between these conflicting dynamics.

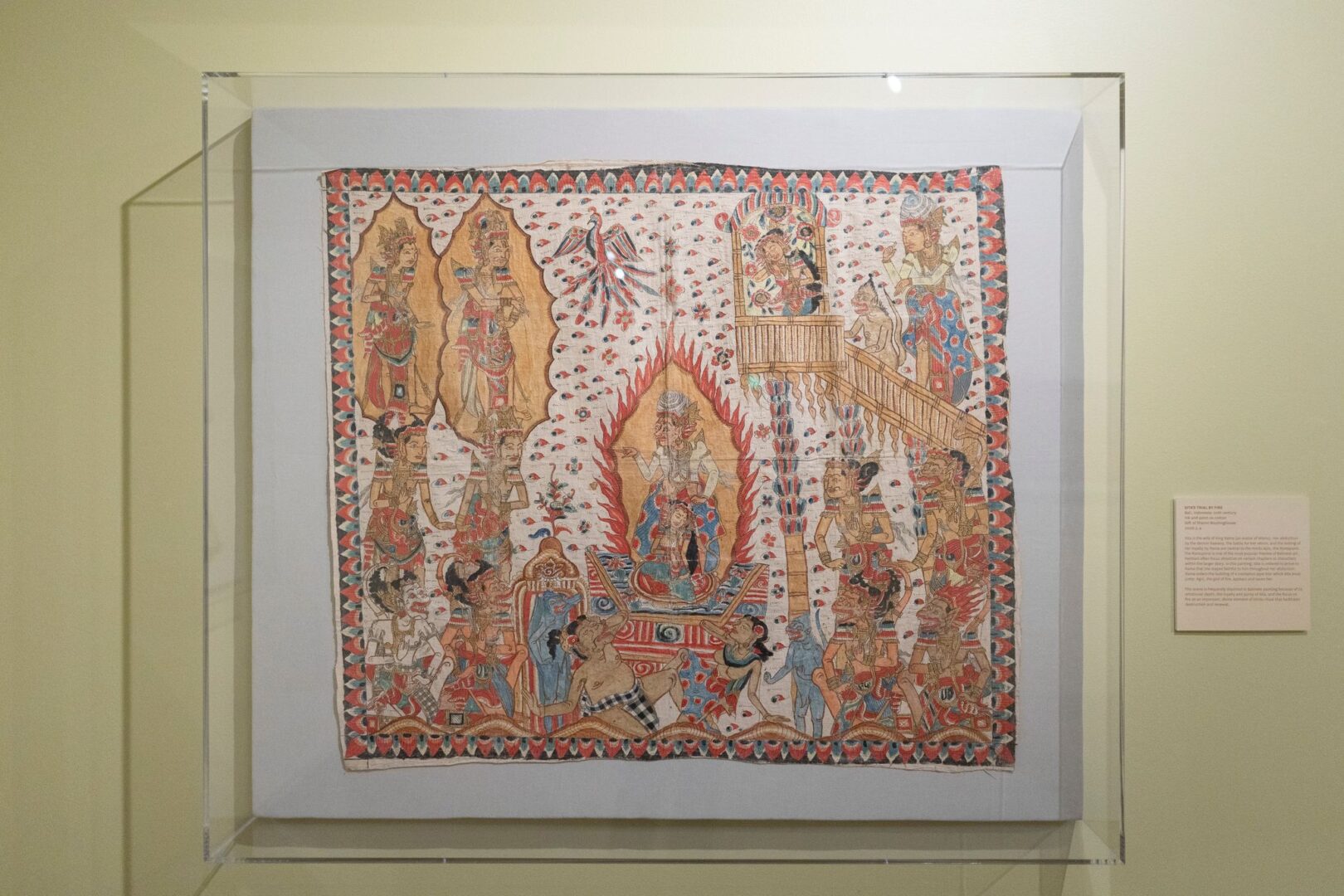

In this gallery, we see two classic style paintings that show how the Balinese painted before the western influence and before they started to paint for outsiders. Hall elucidates, “A common misunderstanding about Balinese art, especially those made before the 1930s, is that non-elite people and their daily lives were rarely depicted. This is untrue. Some of the most lively and compelling works include ordinary Balinese people. This painting, for instance, is about a poor family – the woman has so many children to take care of so the man has to do all the housework.”

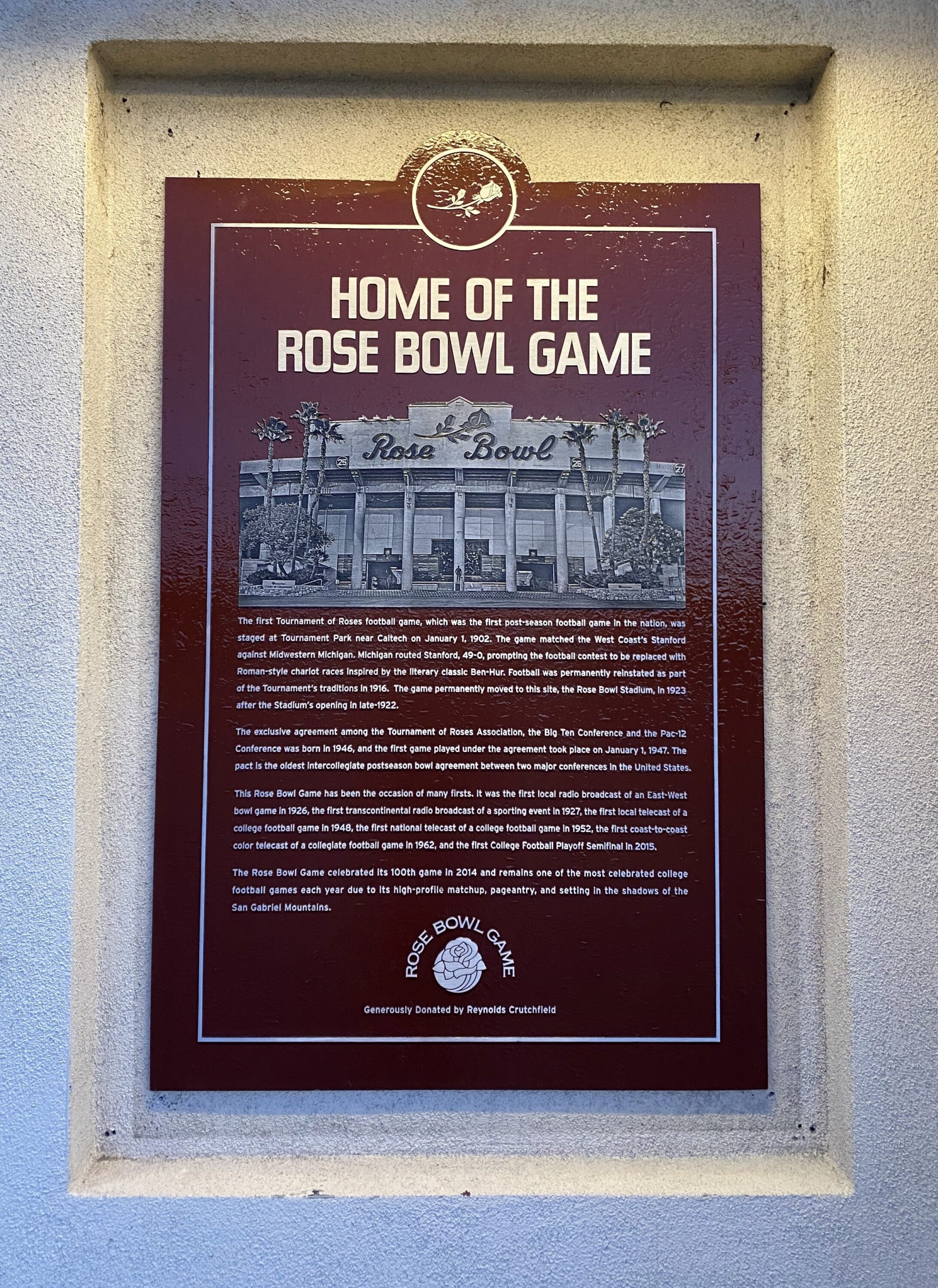

Another is a very popular painting that has been illustrated many times and that’s often thought of a classical artwork on cloth. It’s from the last days of the Ramayana where Rama’s wife Sita has to prove she’s been loyal to him by jumping into a cremation fire. In the scene she’s being saved by the goddess of fire.

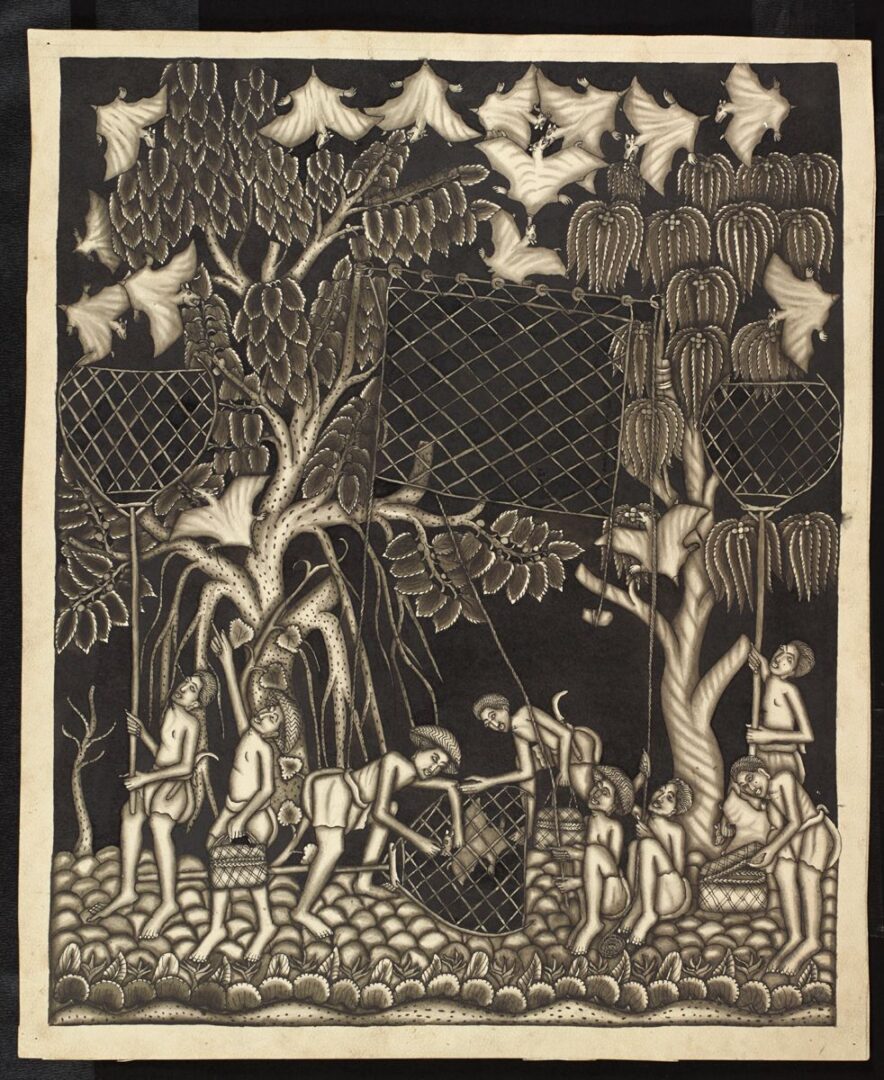

The next gallery gives us a view of how western influence – when Bali began attracting artists, scholars, and tourists in the 1920s and 1930s – changed Balinese art. Hall explains that Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet were both European-born painters who settled in Bali. Spies saw himself as a student of Balinese culture and he was a central resource for visitors to the island interested in learning more about Balinese life, including Bateson and Mead. Both Spies and Bonnet were influenced by Balinese art in their own work and recognized the potential for Balinese artists to create new paintings that would appeal to western tourists. They established an association of local artists called Pita Maha (The Great Light) where they could learn this new style.

While Spies and Bonnet introduced Balinese painters to Western modes of representation, they wanted the artists to find their own stories and ways of telling their lives in this new genre. Bateson and Mead, when they commissioned the artists, insisted that each artwork be an original idea and not a copy. Spies and Bonnet also supported the local artists by purchasing their paintings and giving feedback on their pictures as they experimented with the new form.

Hall points out, “The fact that Bateson and Mead had intended to just go to one village to do their research on development and childhood and schizophrenia, but that they were so fascinated by the paintings they did an entire second study was amazing. They were on the forefront of visual anthropology, study of images and incorporation of visual culture into anthropology. One of the things that was created on film was a 20-minute show of Balinese performances about what people see on the paintings.”

The third gallery shows the artists and the village of Batuan where all the paintings came from. This village was where they had shadow puppet-makers and performances and wasn’t necessarily known for paintings until the 1930s because of the locals’ work with Spies and Bonnet. And when Bateson and Mead paid for some 840 paintings to be made, there became a great interest in Batuan resulting in an influx of money. Batuan, to this day, is known for their paintings; the descendants of these painters continue to create artwork that collectors seek out.

We then enter the gallery where 40 paintings from the Bateson and Mead collection are displayed. Hall states, “The paintings are all very different, they’re all very dense. I organized them into four categories. Village life paintings (in pink labels) show ceremonial procession, hunting for flying foxes, weaving, rituals for new rice, cremation ceremonies, dances – where you see a slice of village life at that time. ‘Popular tales and long-ago events, legends, and mythology’ (in yellow labels) are stories about what happened and why they happened the way they did. They exist outside the European mode of understanding history. How we describe it influences how people see it. The paintings show events the way people believed they did. ‘Stories of power and conflict’ (in purple labels) depict how power comes in many forms – political power, power of animals, power of sorcerers. The last one is ‘belief and the supernatural world’ (in orange labels).”

There’s an iPad in the middle gallery which was created by Lemelson that visitors can watch if they want to learn about the cultural aspects of each painting. USC PAM also commissioned a video documentary for this exhibition. Hall says, “Rob Lemelson sent one of his documentary film makers to the village of Batuan to speak with some of the artists who were descended from and taught by artists whose works are in the exhibition – I Made Tubuh whose teacher/uncle was I Made Jata, Wayan Sundra whose teacher/grandfather was I Ketut Keteg, and Ida Bagus Ketut Panda whose teacher/father was Ida Bagus Made Togog. Additionally, he has some footage from 1997 when he went and interviewed the painters. Rob and his company, Elemental Productions, made this amazing documentary to fill out that narrative.”

The Balinese painters whose works are showcased were asked to visualize their community. At the end of the exhibition, visitors to the museum are asked to do the same in an interactive section. One visitor sketch illustrates ‘Angkor Wat in Cambodia where my mom used to live.’ Another drawing shows a table laden with various Chinese food.

Asked what she wants people to take way, Hall replies, “I think there’s a cultural perspective that a very one-directional interchange occurs when Europeans or westerners go into a non-western area – that these white people would have all the power. And, in the case of the Balinese, that they would paint only what would make westerners happy. But that’s not how it worked at all. That’s part of what the title is about – agency in the Balinese. They didn’t have to do any of these but they clearly loved creating these works. That people from different backgrounds with different interests can come together and develop a whole new genre of art gives everyone involved agency.”

“I want visitors to realize how complex Bali paintings are and I want to pique their interest enough for them to gain a better understanding,” Hall adds. “I want for people to see how rich these narrative modes of storytelling are and how they manifest in these pictures. This is every art historian’s dream!”

Hall herself gained much insight from the experience. She divulges, “I feel I barely scratched the surface… just enough to put together this exhibition. But I would love to learn more about the paintings and the descendants of the painters, and how they connect to what’s happening now. There is a disregard of Balinese paintings because they are perceived as tourist art. But I’ve learned the complexity of it and I really love it. I want to look at more to better understand it, especially Balinese paintings from the 1930s on, and see how they developed.”

“Today they have much larger paintings and they’re very colorful, but if you look at contemporary Batuan paintings you can see how they’re descendants of these painters. They still do scenes of village life but because they’re documenting life in Bali now – you’ll see paintings of cremation ceremonies and there will be tourists and people with phones and cameras. They’ve also incorporated some of the traumatic events like the nightclub bombing in 2002. They reflect what Bali is today and they also create this idealized version of Bali, but you definitely see similar themes. Everything is changing in the new century and I would like to keep my eye out for more things like these to fill out those narratives for people that we often don’t have narratives for,” Hall concludes.

‘Agency’ and ‘power’ may seem the least likely words to associate with Southeast Asians who are, by nature, so agreeable that they are perceived to be submissive. Local inhabitants of islands, like Bali, whose economy relies on tourism, have to be especially warm and hospitable. It’s heartening that the Balinese have found a way to assert themselves – through their art they are reminding temporary residents that the smiling faces that cater to their comforts and needs are human beings with families and lives outside the bubble of a resort.