A study released Monday by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County found fragmentary fossils provide reliable information on the evolution of species.

The study, led by Hank Woolley, a graduate student-in-residence at the museum’s Dinosaur Institute, examined incomplete fossils and sought to discover which species they came from, what were the organism’s closest evolutionary relatives at the time and how the ancient organisms relate to organisms alive in the modern day.

“We often only get to hear about excavations of exceptionally complete fossil animals and plants, but in the background, the majority of the collections that paleontologists make in the field is made up of incomplete and fragmentary fossils,” Woolley said. “It’s historically been hard to quantify how trustworthy these fossils are, since they’re so incomplete.”

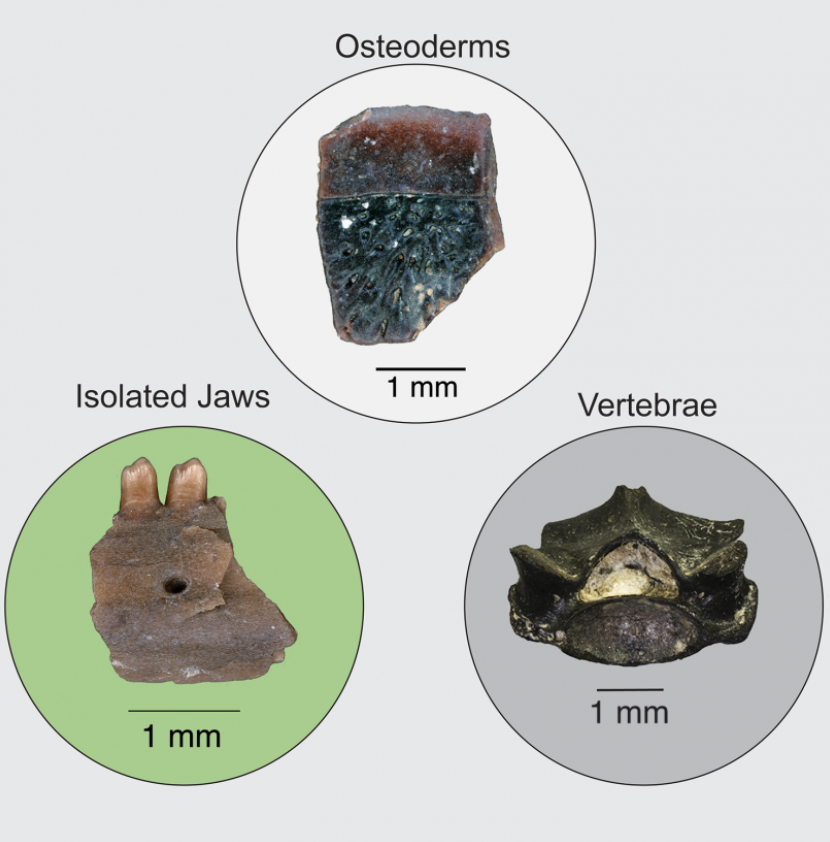

Woolley and his research team used 6,500 specimens from the Natural History Museum and other major natural history collections of fossil squamates, the group including lizards, snakes and their extinct marine relatives, mosasaurs.

The researchers identified the most common partial fossils across the collections, capturing key features such as jaws, teeth, ribs and vertebrae that indicated how closely the ancient species were related to one another.

Woolley and his team also used a series of sophisticated comparative methods, metrics and tests to show that the fragmentary fossils did not conflict with modern interpretations of the evolutionary relationships of lizards, snakes and their relatives.

“This is exciting, because results like ours increase the scientific value of incomplete specimens housed in museum collections, and that allows us to include more of Earth’s extinct biodiversity as we continue to piece together the past,” Woolley said.

“Even these incomplete fossils can guide our knowledge of evolution, so we can be more confident in our placement of these paleontological twigs on the tree of life.”

The study concluded the fragmentary fossils that make up the bulk of paleontological collections contain reliable information on evolutionary development, which the researchers argued demonstrates the importance of natural history collections for future research.

“The more complete our picture of the past is, the more capable we will be in accurately predicting and managing changes in today’s ecosystems as the climate crisis and global change continue to impact life on Earth,” the museum said in a statement.