Law professor Paul Bergman knew very well that teaching a roomful of college students about an evidence course could get boring. He was also aware that some of them probably stayed up late studying – or partying, as young people at university are wont to do – so he could only go on lecturing for so long before he lost their attention, or they fell asleep.

Bergman started teaching at UCLA in 1970 where he spent the first decade supervising students on actual cases with real clients. He usually had only 12 to 15 students because there was a limit on the number of clients he could work with. A lot of class time was devoted to discussing case strategies so he could help students learn from each other’s experiences. But by the 1990s, he started teaching evidence and other podium courses taught in a large classroom.

“Traditionally, you either read and analyze appellate court cases or you look at real evidentiary issues and discuss those in class,” explains Bergman who is now an emeritus professor at UCLA. “So I thought it would be interesting to present a little courtroom scene from a movie and analyze it as if it were a real courtroom event. They may not be totally accurate but things go on in actual courtrooms that shouldn’t go on either.”

When he looked for a source for these courtroom movies, however, Bergman discovered that while there were several books about practically every other movie genre, there was none on courtroom movies. And proving the adage that necessity is the mother of invention, he resolved to rectify this omission.

“I thought, ‘Well, I’m an academic, I should write one,’” Bergman continues. “I only wanted to write about movies that I had actually seen. But in 1994 there were no DVDs; some of the films were available only through the UCLA film archive so I had to go into the basement of a Hollywood building and someone had to change the reel every ten minutes. I asked Michael Asimow, whom I’ve collaborated with on other law publications if he would be interested. Together we watched and analyzed 150 movies, including such classics as ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ ‘Inherit the Wind,’ ‘Anatomy of a Murder,’ and ‘A Few Good Men,’ which was out by then. In 1996 our first book called ‘Reel Justice: The Courtroom Goes to the Movies’ was published.”

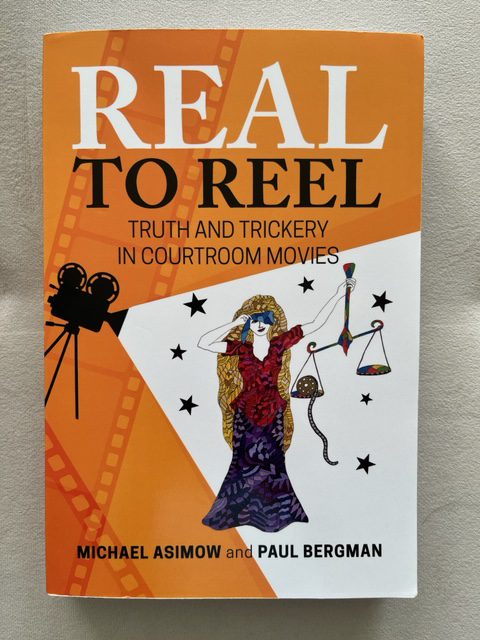

Response to “Reel Justice” was very positive and led to the publication of a second edition in 2016. It has also been published in China in a Chinese language edition. Then in 2020, during the pandemic, Bergman and Asimow embarked on writing a follow-up to “Reel Justice.” Fortunately, this time around, the movies they chose were available on DVDs, Blu-ray discs, and streaming on cable. “Real to Reel: Truth and Trickery in Courtroom Movies” was published in May 2021.

“All the movies from ‘Reel Justice’ were integrated into this new book, which we divided into chapters based on themes,” describes Bergman. “The difference is the first book mainly discussed the story of the movie. For our sequel, we introduced a new format which focuses on the courtroom proceedings – it’s more of an analysis of the courtroom action and its messages about law, lawyers, and the legal system.”

“Courtroom movies often have a twist ending or a climax that you don’t see coming,” adds Bergman. “In ‘Reel Justice,’ we revealed the ending with a ‘spoiler alert’ warning. For ‘Real to Reel’ we stopped short of telling people how it ended; instead we directed readers to the appendix. We want to encourage our readers to actually see the movie for themselves first so we don’t want to give it all away and spoil it for them. Of course, some people don’t really mind knowing the movie’s conclusion and would still watch it anyway. But this time, we gave readers an option.”

Bergman, who received his J.D. from UC Berkeley (Boalt Hall), clerked on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and was an associate at Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp in Los Angeles before entering his teaching career, has penned more than 50 law review articles and book chapters on a wide range of subjects, including the images of law, lawyers, and justice in popular culture. One of his award-winning essays discussed the contribution of the 1970s TV show Emergency! to the development and legalization of the paramedics profession. Another article examined the ethics and lawyering techniques of Horace Rumpole, the crusty barrister featured in the classic British TV series Rumpole of the Bailey. He has also written a book chapter that describes different uses for film clips in a law school Evidence course.

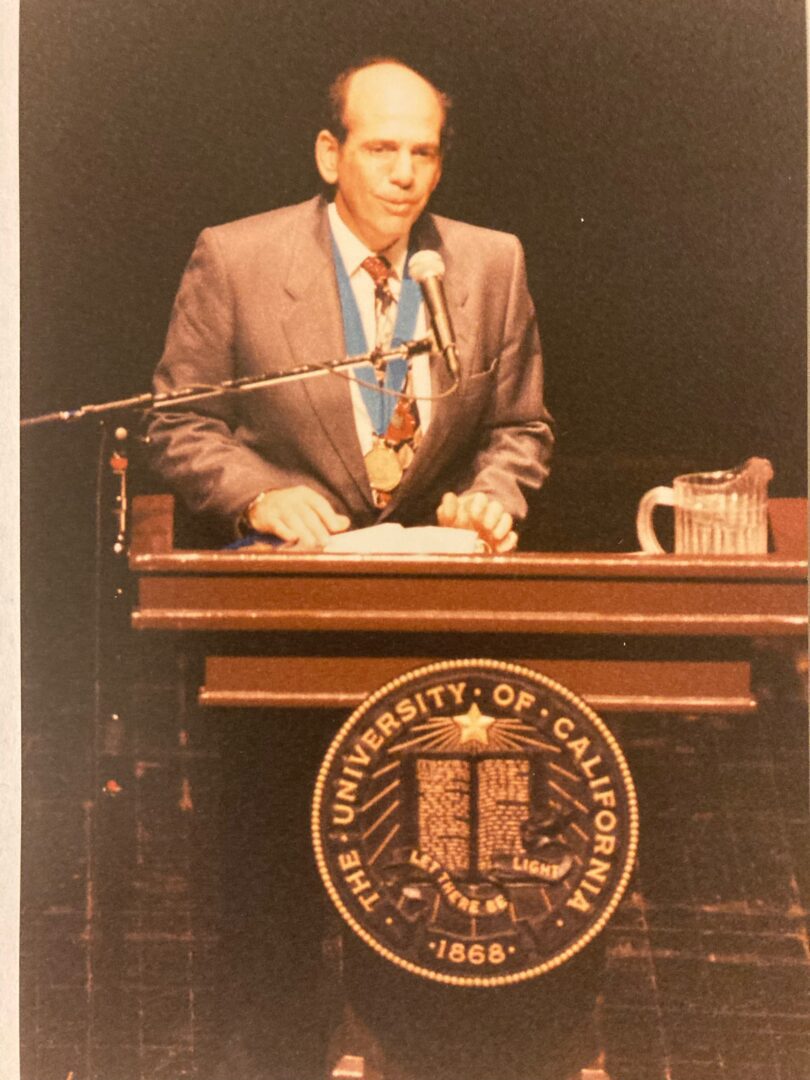

A respected academic, Bergman’s teaching awards include: The University Distinguished Teaching award; The Dickson Award for distinguished service and scholarship by a UCLA Emeritus Professor; and the American Board of Trial Advocacy Award for trial scholarship and teaching.

An unexpected, gratifying consequence of the publication of Bergman’s first book was the recognition he received for his contribution to the field of law. He has given film clip-based presentations to groups of lawyers and judges all over the country as well as in the UK and Japan. He has also appeared on numerous radio and TV shows, including The Today Show and the nationally syndicated radio program Champions of Justice.

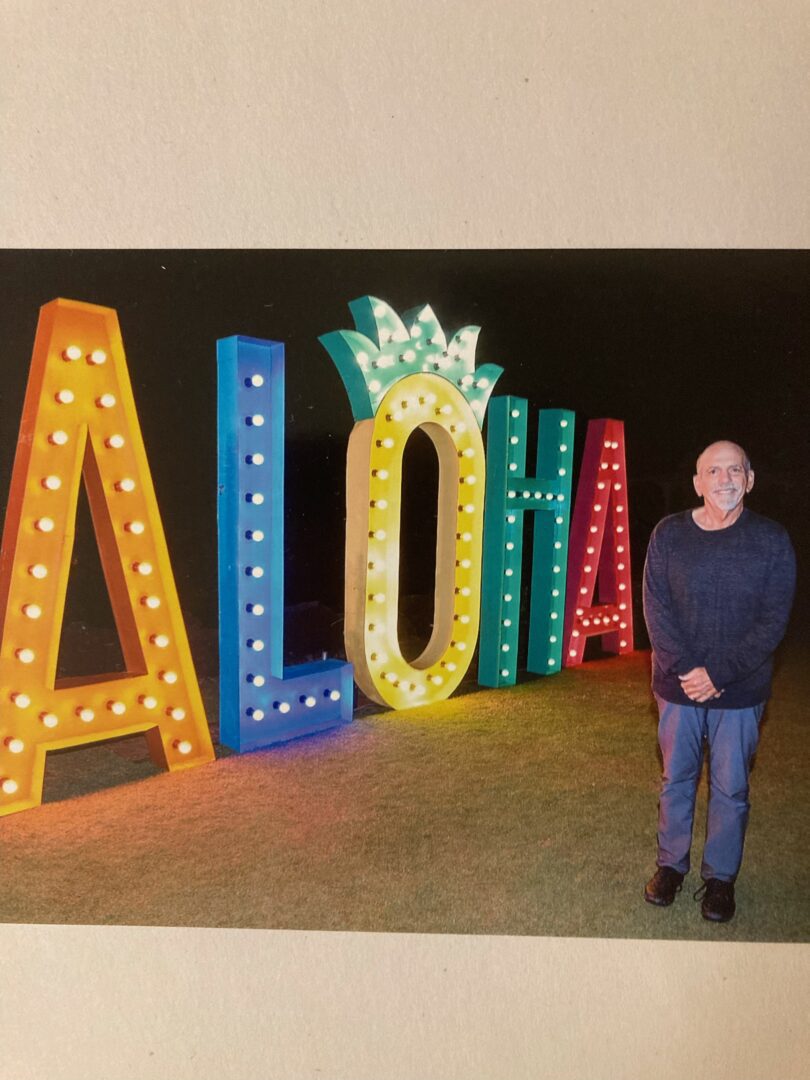

Expounds Bergman, “It’s given me an opportunity to share films … I’ve spoken at conferences in Washington D.C. with supreme court justices. My personal life has expanded because of the people I meet when I bring them my love for movies and why they’re important. We haven’t done any of that for this new book yet because of Covid but I’m scheduled to give a presentation at the International Society of Barristers in Hawaii sometime in March.”

Many lawyers might look askance at others in the same profession who watch courtroom dramas which aren’t real. However, people’s perceptions about the courtrooms, law, lawyers, and the justice system, and their expectations from these are the reality lawyers, judges, and those connected to the justice system have to contend with.

Bergman defends the genre’s place in everyday life. He says, “For most people, it’s always a bit real. Like I tell my law students, when you meet a new client or a witness, they think they know a lot about you. But what they think they know is not based on meeting you and it’s probably not based on meeting a lot of lawyers. It’s because they’ve watched a lot of movies and TV shows about lawyers and they think they know what’s going to happen. So the messages these movies send about lawyers, the law, and the legal justice system influence how people behave with you and react to you. Movies have an impact on people’s lives even if they’re not accurate. This is how people think ‘Jeez, I didn’t realize this is how trials are like.’ There’s a theory that people remember content but they don’t remember the source. The messages in these movies are important – whether they’re right or wrong. And sometimes they’re a little of both.”

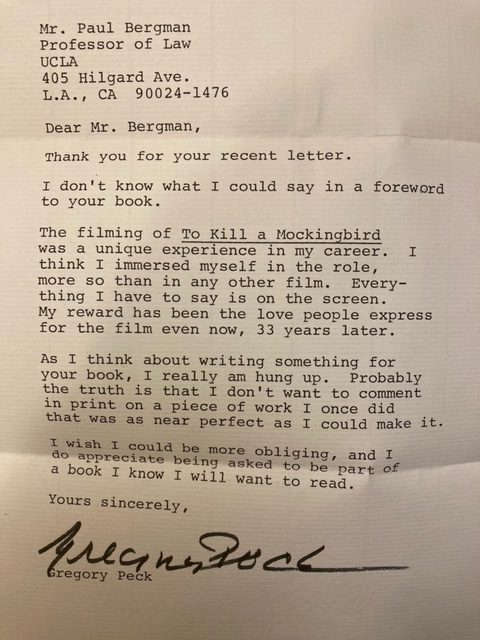

Being cinephiles, Bergman and Asimow enjoy rating the movies in the books they wrote. Much like film critics, they rank movies on a one-to-four gavel system – four gavels for the classics. Moreover, Bergman doesn’t cloak his admiration for the actors who made big impressions on audiences. He has always been a big fan of the movie “To Kill a Mockingbird” and its lead Gregory Peck. In fact, when he finished writing “Reel Justice,” he sent a letter to the actor requesting him to write the foreword to it. Gregory Peck responded but declined. Bergman mailed him a copy of the published book anyway and the actor sent a letter saying “Your book, written with Michael Asimow, is excellent, fascinating. I have read many of the cases including To Kill a Mockingbird and The Paradine Case.” In the letter, Peck further disclosed, “I quite agree with your evaluation of The Paradine Case. On matters concerning the script, there was dissension between Selznick and Hitchcock. Selznick prevailed and pumped up the love triangle in a way that went against Hitchcock’s grain. It was the last picture they made together.”

Movies, like theatre, – and what’s more akin to theatre than courtroom drama – are a mirror we hold up to ourselves. They reflect society and popular culture. And because movies, like plays, are written by people with beliefs and convictions, and directors have perspectives and points of view, these often are embedded within. Inevitably, movies can foreshadow what’s to come, effect change, and even change laws.

In the movie “Adam’s Rib,” director George Cukor filmed Katherine Hepburn – who played the role of Amanda Bonner – addressing the jury. But because the camera was facing her, in essence, she was speaking to the viewers. It was released in 1949, two decades before the advent of the women’s liberation movement. In the play and film version of “A Few Good Men,” playwright and scriptwriter Aaron Sorkin successfully and memorably “dramatizes and personalizes an abstract issue such as the legitimacy of using civilian norms to evaluate military discipline.”

“Real to Reel: Truth and Trickery in Courtroom Movies” marries Bergman’s love for movies with his advocacy for the law and its practice. Its dissection of courtroom events is interspersed with asides that reveal his wry humor. It could easily win over even those with an innate distrust of lawyers.