The City of Monrovia will honor longtime teacher/principal Almera Romney with a Neighborhood Treasure – right near the site of her beloved Huntington School – now Canyon Early Learning Center.

“Ali” as people called her was born in central Utah, the daughter of immigrant Danish Mormons. In rural Manti – where Almera became a teacher at 19 years of age – the only “minorities” were non-Scandinavians or non-Mormons.

In 1934, Romney followed her husband, Clyde, to Southern California with intentions of being a homemaker to their three children, Mary Ellen, Jane, and Clyde. Her husband, who was a salesman, became sickly and Almera needed to find work. She appealed to Monrovia’s Superintendent Dwight Lydell who told her that she would not really want to fill the opening as a fifth-grade teacher at Huntington Elementary – the “Negro school”.

Almera remembered Lydell’s words, “The problems are insurmountable. The children are undisciplined and can’t learn; the parents are ignorant; and the school’s as dirty as a pigpen.”

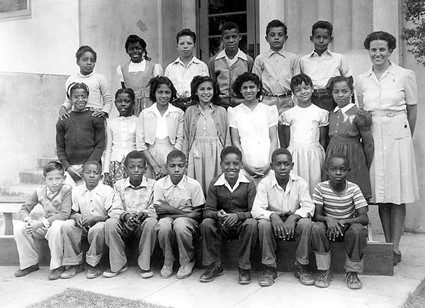

Huntington Elementary was the segregated school for African Americans, Mexican Americans and Asian Americans in Monrovia. Although Monrovia was racially integrated into the city’s earlier beginnings, by the 1920s, social segregation became the norm in schooling, housing and from movie theater to the swimming pool. The “Negro” school had substandard everything from books to sporting equipment to building structure. Romney became a Huntington teacher in 1946.

Who knew that it would be Mrs. Romney who would tackle Monrovia’s systemic racism?

She had never even met a person of color prior to this assignment. In her first year, Mrs. Romney won the children’s loyalty by dressing outlandishly for Halloween and demanding that Monrovia Library give all her class library cards. Her youngest child, Clyde, became the only white kindergartener at Huntington.

After three years, Mrs. Romney took on a harder responsibility as principal of Huntington. She had to fight a District hell bent in preserving de facto racism. Monrovia has the distinction of being one of the last school districts to desegregate in 1970.

Romney is described as strong, compassionate, professional and an advocate of high standards. As she fought for equal rights to a future for her students, she collected many admirers.

In 1951, Romney’s husband died and left her in debt and a single mom with three children. The African American community didn’t want to embarrass Ali by supporting her at her husband’s funeral and carefully selected three representatives.

Her first Christmas Eve as a widow, she wrote that she had a “loneliness almost more than I could bear.” Later writing, “The [African American] custodian and his wife [came] bearing a freshly baked, beautifully decorated cake. ‘We knew this would be a difficult time for you. We’ve come to visit for a little while.’” Almera had found a “sweet feeling of peace”.

Almera was one that understood that educators have community responsibilities, and she was a leader in Monrovia’s then Human Relations Committee, Coordinating Council, and the Santa Anita Family Services Board.

Almera Romney helped chip away at Monrovia’s color wall and encouraged so many youngsters to believe in a better future. Ali was a great gardener who favored ranunculus at her 209 W. Lemon address. She was also a great cook, well known for bean soup, lemon cake, and Danish dumpling soup.

Perhaps even more of a lasting legacy, several of Almera’s own children and grandchildren also became teachers and touched more lives. Some of the Huntington children are now grandparents still living in Monrovia. Romney’s genuine care for a better community is forever.