Path to the pros littered with horror stories, systematic mistreatment

The number of ballplayers under contract in the minor leagues is tough to precisely nail down.

No one farm system is grown and cultivated the same. In July 2018, The New York Yankees had 340 players signed to their franchise, 50 more than any other Major League Baseball team at the time. A Baseball America estimate from that same summer pegged the median number of players per organization at 275-280.

With that in mind, and excluding non-affiliated leagues, it’s safe to estimate the total number of players bouncing between the majors and the minors is in the range of 8250-8400.

A reasonably sized sample, but not exactly insurmountable for the aspiring athlete. There are more than enough minor league baseball players to fill, say, Dunkin’ Donuts Park, the home of the Hartford Yard Goats.

Yet making it to the pinnacle — earning a cherished spot on the 25-man roster of a major league club — that’s a much tighter target.

Simplified, over 8,000 dreams remain alive at any given time in professional baseball. And in recent years, the public has learned the climb to the clouds isn’t a pretty one.

In fact, many of the stories are nothing short of repellent. Multiple players from the Brewers’ Triple-A system came together to pay for a one-bedroom apartment in Nashville, only to find a space that was completely infested by cockroaches. The Mets’ Double-A roster lived in a facility that lost running water and electricity and didn’t get it back for three straight days. Countless pictures of food have circulated that show meals laughable by most standards, let alone the standards of premier athletes.

Much like the potential of making a big league roster, having a positive experience in Minor League Baseball (MiLB) is a rarity — it takes a near-perfect situation to make it feel worthwhile. Ethan Chapman, a California-based baseball agent for Full Circle Sports Management, only managed a positive experience thanks to plenty of support and variables swinging in his favor.

Chapman was drafted by the Kansas City Royals in the 30th round of the 2012 draft. The Upland native played for Cal State San Bernardino ahead of his selection. He grew up in a very supportive family, and he stated that the Royals organization took great care of their players.

“I was just married, and my wife made a stable enough income for me to keep playing. My family was very supportive, helping out financially and buying us meals. And truly I wasn’t in a position where I had to pay for much as a ballplayer. Kansas City took care of us. But I know we’ve been hearing stories that aren’t consistent with that,” said Chapman.

He noticed that players would be drafted and enter the world of the major leagues without proper guidance. Chapman wanted to be the person that could prepare upcoming talent for the glories and failures that come from a lifestyle in baseball. After a stint with the Phillies organization and some time spent playing in Mexico, he retired from the sport he loves to become an agent. He believes he can lend some of that fortunate support he had.

“They need to know the ups and downs of this sport,” he mentioned. “Being in this sport right after college ball means there will be times when you strike out three or four times in a game, or that you’ll give up multiple home runs in consecutive innings. For me, it’s about teaching them how to get over those mental hurdles.”

The MiLB, particularly lower affiliate teams, generally fail to mimic similar fan interest — all the while presenting stronger talent that has something to prove on an unsatisfactory salary.

So often, guys that get drafted experience glory before their names get called. They are the stars of their teams. They play for a college club that has a stout following.

The shift to the minors can be a shock to the system.

“Most of these guys that are scouted are coming from power five schools,” Jared Schlehuber, a scout for the San Fransisco Giants and former teammate of Chapman, said. “And let’s face it, the minor leagues compared to college ball is just a completely different environment. Once you make it to the minors, you are playing professional ballplayers. There’s nothing easy about that, and I think that’s initially lost on kids who are drafted.”

Being drafted and placed in a farm system, nevertheless, is an outlier. A majority of minor leaguers and independent ballplayers are attempting to reach their dream in the form of a tryout; crawling their way through club after club for a shot at the pros.

So was the case for Eric Dawson, a former Hope College Flying Dutchman.

His college career kicked off in furious fashion. Between his freshman and junior year, he struck out just 13 times in over 500 at-bats.

“I was voted the most difficult out in NCAA baseball, or something like that, my sophomore year,” Dawson said.

But when his senior season rolled around in 2014, he decided to hang up his cleats, at least temporarily. Until the bug came back a few years later.

He decided he was going to test his mettle at a high level again, joining an independent minor league team in New York at age 26.

“It was one of the best summers of my life when playing again,” he mentioned. “I started going to cages every day and working on my game. And for a moment I thought to myself ‘Damn, maybe I’m better at this than I initially thought.”

He decided to chase that coveted baseball dream — a dream that led him into a few different extreme environments. He drove his Prius through a blizzard into Ontario, Canada for a tryout. He played with a Florida-based group of self-proclaimed “baseball bastards” named the Black Sox. He readily uprooted routines and regularity to hustle towards that highest high of America’s pastime, learning along the way that the valleys probably should be a little bit more advertised than the peaks.

“As a kid, my parents reminded me of how tough it is to become a professional player. My dad who pursued professional baseball himself mentioned that the best advice he ever received was to not waste his time. And they passed that on to me. But I eventually did start to dream later in life,” Dawson said. “I’ve learned now that the ‘dream’ is more propaganda than anything else.”

Failure has just become part of the experience, and for independent players and top prospects alike preparing for the worst seems to be the most feasible lesson to learn. Regardless of expectation, though, the so-called dream regularly dies after being in a position where a more obtainable career and salary is the only option left to survive in the real world.

Ryan Fagan, a senior MLB writer for Sporting News, conducted a study after the reveal of the MLB’s minor league contract restructure before the 2021 season, which saw minor leaguers receive a much-desired pay boost. However, even with that push from the MLB, a Triple-A player’s minimum five-month salary of $14,700 is far lower than other leagues. G-League players for the NBA make at least $35,000 per season, and developmental players in the NHL have a minimum salary of $52,000.

This chart, however, does not even take into account the lowest affiliates in the minor leagues. That same study also noted the minimum salary for Double-A players ($12,600) and Single-A players ($10,500) are even more disappointing. Even with the 72 percent salary increase that Single-A players were awarded for the 2021 season, players were averaging less than 80 dollars per game.

Nevertheless, part of the minor league journey is knowing that financial hardship is an inevitability.

“When I played for the Royals organization, I knew what I was signing up for. I grew comfortable with the pay and made it work. And that five-year playing experience helped build the foundation for my growth in professional baseball,” Schlehuber stated.

What minor league players do expect, however, is stability — that their organizations will provide them with the proper tools to succeed and the necessities to survive.

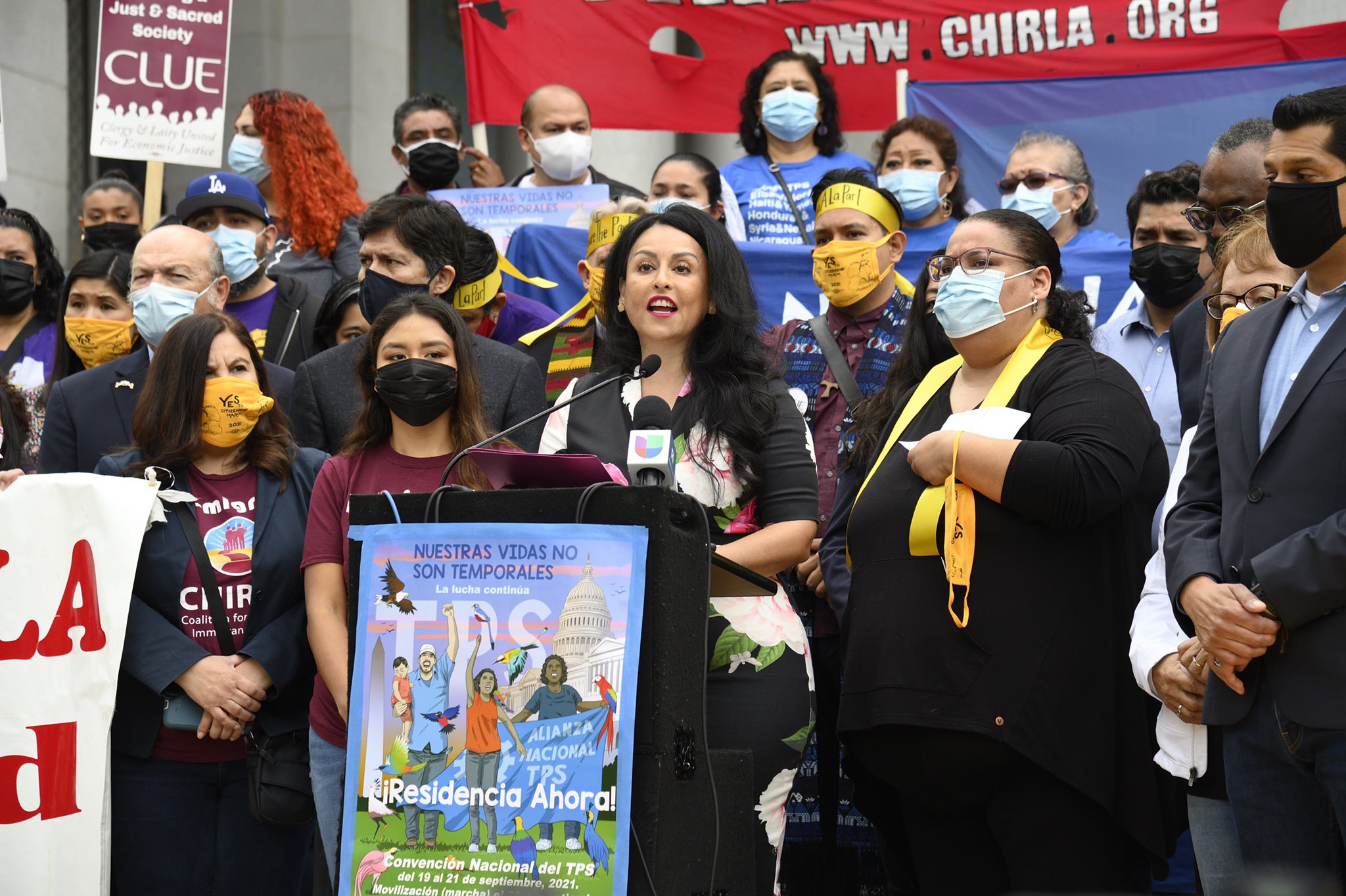

More and more players from all over the MiLB have opened up about their experiences during the 2021 season. One of the organizations that have been under heavy scrutiny has been Southern California’s own Los Angeles Angels.

Kieran Lovegrove, a pitcher drafted in the third round in 2012 from Mission Viejo High School in Orange County, was one of the first minor leaguers to speak on his challenging experience with the Angels. He was a traveled veteran who had played for nearly a dozen different teams. In July, he spoke up about his time with the Rocket City Trash Pandas, the Double-A affiliate for the Angels.

He pinpointed the universal concerns: poverty-level pay, unlivable housing conditions, needing to work other jobs in order to live. But more than that he opened up about his depression, anxiety, substance abuse and attempted suicide. He called out Angels’ owner Arte Moreno, saying “Moreno wouldn’t have his kids live like this.” Lovegrove went as far as to say that the minor league is plagued by a “mental health crisis.”

The feelings that Lovegrove expressed were mutually accepted by his teammates, and when ESPN’s article was published the team read it together in their clubhouse and cheered in relief. And since then, more Trash Panda players have spoken about their time with the Angels organization, including catcher Michael Cruz, who has spent extended stints of his six-year minor league career living in his car.

Players from the Angels Single-A affiliate, the Inland Empire 66ers, have echoed similar concerns about sub-par conditions.

The Angels organization and Moreno himself have spoken little on the matter.

Speaking up wasn’t always the norm due to fear of retaliation from higher-ups, but Lovegrove’s willingness encouraged a groundswell that has placed significant pressure on the MLB. More frequent open discussion, along with the development of non-profit groups such as Advocates for Minor Leaguers are steps, but the problems remain pervasive.

Dawson, who is now a licensed sports social worker and specializes in mental health services, believes that the crisis which Lovegrove mentioned is very much in play for most minor leaguers. Whether it be from his friend who was drafted early from the University of Alabama or from the members of the clubhouses he spoke with at length during his independent career, he has learned about the widespread mistreatment through conversation.

Dawson believes players encounter a new opponent in identity.

“Organizations need to listen to their players, that’s the first thing that needs to take place,” Dawson said when asked about ways to address the matter. “But for the players themselves, being in that space is a sudden shift in their identity within the game. Players get drafted and they are being talked about in their towns or their colleges. But then they deal with a much different reality in the minors. I can’t even imagine how disenchanting that must feel.”

Not all organizations have ignored their players’ cries for help. Many teams have committed to providing services such as housing stipends and extended pay throughout Spring Training. One of those teams was the Giants, and Schlehuber gave a lot of credit to the front office for taking that initiative.

“I know that we (the Giants) really placed an emphasis on paying minor league players during the pause from Covid. And now we’re in the process of building a $16 million facility just for our minor league talent,” Schlehuber said proudly. “That all starts with the front office, all the way down from (general manager) Scott Harris to (director of player development) Kyle Haines.”

But the issue is there isn’t an extensive league-wide policy that forces teams to push for better conditions in the minors. Progress was made on Oct. 17 when the MLB announced that they introduced a motion to require all 30 organizations to provide housing to their MiLB talent. Everyone within the league, along with the leaders of advocacy groups, agree that this pursuit is a major step forward.

Yet questions still remain with the intricacies of the decision, as there are some unclear details about which players are eligible to reap that benefit.

But why did this take so long, and why didn’t the league push for even more precautions? Even though COVID-19 affected the league’s ticket sales, the MLB is not struggling financially. In fact, the focus on television deals in 2020 brought in a revenue total of $3.66 billion between all 30 clubs in 2020 alone.

And despite the financial empire that the MLB has built over the last several decades, the league still finds ways to make sure their minor league talent is receiving a poverty-level salary. One of those strategies went through Congress in 2018 — a year where the MLB collected a record-setting near $10.3 billion — with the “Save America’s Pastime Act” signed under the Trump administration.

The spending bill, which was written in response to a lawsuit that was expected to lead to increased minor league wages, announced minor leaguers as “seasonal employees.” Because of this, it was announced that those players are exempt from the protections of the Fair Labor Standards Act, meaning they were not eligible to receive minimum wage rates nor were they subject to overtime laws.

It is rare to find a seasonal position in any workforce similar to the MiLB; where its employees are required to work six or seven days a week to go along with an extensive travel requirement. The MLB, though, has approached this issue the same for several years.

Their philosophy is to find a way to legally pay minor leaguers as little as possible.

“They are doing what they love, but it’s also a job, meaning they deserve a proper income,” Chapman said. “Especially when there is so much money in this game. I’m not really sure how this gets corrected, and I’m not sure whose pockets that money should come out of. But I believe that these players deserve the right to focus on competition and be able to train and focus on baseball without having to earn side gigs to make ends meet.”

Money is not, and has never been, the issue that MLB can point at. Rather, it is a consistent lack of attention and care which organizations continue to place in their farm systems that deserves the highest blame.

The 2021 season has proven that, and 2021 has proven that change needs to happen soon.