By Susie Ling

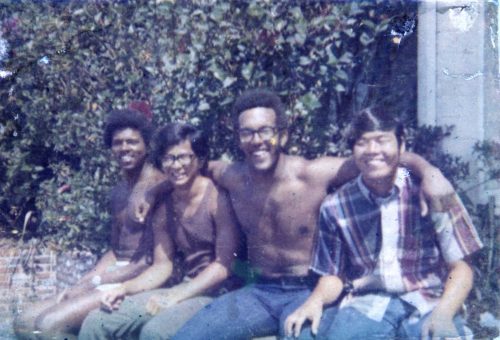

Marvin “Oka” Inouye was playing on Evergreen and Ivy — in the middle of the street. His neighbor, Barbara Jean (now Williams), insisted the 5-year old step back on the sidewalk. That’s how Marvin met his “other” mother in 1956. For six decades, Marvin was best friends with Barbara’s oldest son, Marcus Lewis, and in and out of Barbara’s homes.

But it was only recently that Marvin came to realize that this was not the first time that Barbara Jean, an African American, helped her Japanese American neighbors. Barbara, née Marshall, grew up in the J-Flats community of Los Angeles, between East Hollywood and Silver Lake. In the middle of this Japanese American immigrant community was the home of the Marshalls. One Japanese American alumni of Dayton Heights Elementary, Colleen “Teeny” Kunitomi, said, “I used to wonder how this African American family got in the middle of all these Asian immigrants.” Actually, it was Barbara’s grandparents, former slave George and Josephine Albright who homesteaded the property as early as 1892. Their daughter Crystal would also settle on Westmoreland Avenue with her husband, Rufus Marshall. They owned a catering business while raising three children: Josephine (Burch), Rufus, and Barbara Jean.

As the Japanese American population grew around them, the Marshall family accepted and adapted. Barbara, now 93, said, “We lived between the Kakiba and Hoshizaki families and we were always exchanging food across the hedges. In fact, my mother suggested I go to Japanese language school with our neighbors. We even had a koi pond.” Mr. Kakiba worked for the Dolly Madison bakery and the Hoshizaki’s opened Fujiya Market on Virgil Avenue in 1932, so there was some good food passed over those hedges.

Barbara said, “But in 1942, the president at the time changed everything. My household was disrupted as my neighbors’ households were disrupted. It was heart wrenching.” On the day the Japanese Americans had to report to unjust internment, it was Barbara’s mother that worked endlessly in the kitchen feeding all her Japanese American neighbors a last good hearty breakfast of biscuits, eggs, and coffee. Barbara remembers, “She was cooking and cooking.” And it was Barbara’s father who drove one family after another in the dismal rain to the designated meeting spot for the internees. In the weeks following, the Marshalls packed chicken pies to pass across the fence at Santa Anita Assembly Center. Dr. Takashi Hoshizaki, then 16, remembers “Nana” passing in the best apple pie with puffed-up crust and ice cream. From Santa Anita Assembly Center, most of the Dayton Heights Japanese — like the Monrovia Japanese — were interned at Heart Mountain Concentration Camp in Wyoming.

The Marshalls did more. Joann Kakiba Asao, now of Monrovia, said between grateful tears, “The Marshalls stored a trunk for my grandparents. After the war, we still had our precious kimonos, our shamisen, and our Japanese dolls. My grandmother was a seamstress and my aunts were Japanese dancers.” The Marshalls also were given power-of-attorney to protect property and bank accounts for some Japanese Americans.

More recently, Barbara thought to visit Manzanar Concentration Camp off Route 395 with her other son, Eric. But she never got out of the car. Eric said, “She just cried and cried thinking how desolate and unjust these camps were.”

Marvin’s sister-in-law, UCLA Professor Judy Mitoma, said, “This is a beautiful story of beautiful hearts. The Albright-Marshalls found a safe space from racism to grow their families. This was a family that had survived slavery; everything else is tempered by those roots. That was the seed. They shared their food, their caring, and their love with others who came into their neighborhood. This is the history of a lineage.”