By Félix Gutiérrez

As America honors women and men who answered their nation’s call to duty on Veterans Day next Monday, Monrovia may wish to remember Pvt. Louis Ramón García, killed in action in France on Oct. 16, 1918, a few weeks before the Armistice ending World War I on Nov. 11, 1918.

Pvt. García and his Monrovia hometown are posted in records of the California War History Committee. Monrovia is under his photograph and name in the book “Soldiers of the Great War.” When he entered the Army in Los Angeles on June 5, 1917 he gave Monrovia R.F.D. (Rural Free Delivery) 1, Box 525 as his home address.

Born in Tucson in 1890 to Homobono and Mercedes García, who came to the United States from Sonora, México, he traveled with his family in a horse-drawn wagon to the San Gabriel Valley after 1900. By 1910 he was living in Duarte with his Tío Serapio and Tía Florentina García and picking oranges with his uncle on the CC Davis Addition to Duarte.

The next year he was in Monrovia, living with sisters Clotilde and Jesùs at 801 S. California Ave. and working as a laborer. In 1917 sister Mercedes came to Monrovia after marrying cement foreman Francisco J. Gutiérrez and moving into his home at 427 E. Huntington Drive. Both homes were “south of the tracks,” Monrovia’s segregation line.

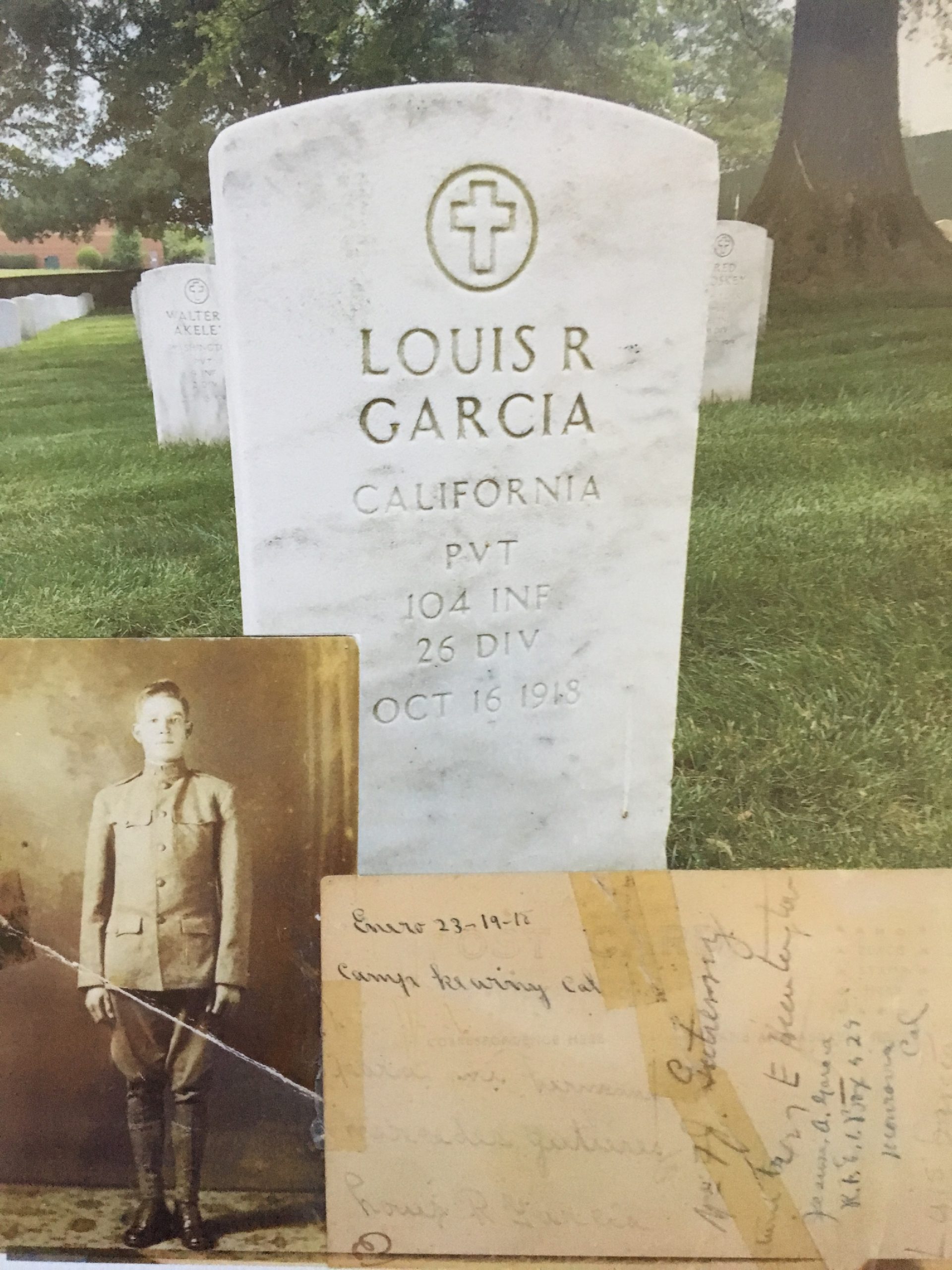

García’s Army service began with infantry basic training at Camp Kearny near San Diego. He was a proud soldier, sending a Camp Kearny picture postcard of himself standing in Army uniform to Mercedes in Monrovia on Jan. 23, 1918.

“Para mi hermana Mercedes Gutierrez” (For my sister Mercedes Gutierrez), read his postcard note. Five months later, on June 28, 1918, García shipped out of Brooklyn, N.Y. to the European battlefields. Four months after that, on Oct. 16, 1918, he was killed in action in France while fighting with the Army’s 104th Infantry 26th Division.

“While ‘Over There’ in France, the men of the 104th Infantry Regiment experienced some of the heaviest fighting and suffered the greater number of casualties of the U.S. 26th Division,” a history of the unit reported after the war.

In October 1918 the 104th and other American and French units were engaged in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive trench warfare to break enemy lines and take prisoners. The Germans defended their positions by counter attacking with artillery fire of poison gas and explosives.

Pvt. Louis R. García was killed on the day the 104th infantry fought alongside the French 17th Army Corps and French 18th Division in “an attack for the purpose of obtaining possession of the Bois d’Hamont on Oct. 16, supported by tanks,” according to a service narrative compiled for the 26th Division’s return home in 1919.

On Nov. 21, 1918 the Los Angeles Times reported García was one of three Southern Californians “killed in action.” He and other war casualties were first buried in Europe, then transferred in the early 1920s to Arlington National Cemetery outside of Washington, D.C.

Classified as White by the military, García is buried in an Arlington section reserved for Whites, but would not have been if his body was returned to Monrovia. When I visited his grave two years ago I saw across the lane the segregated graves of African Americans killed in action. Last year my sister Lorraine and I visited Monrovia’s Live Oak Memorial Park to view the graves of Louis’ sisters Jesús and Mercedes and other family members.

I mentioned to a cemetery staff member that most of our family is buried in Live Oak and one was buried in Arlington National Cemetery after being killed in World War I. He said that if Louis R. García’s body had been returned to Monrovia he would have not been buried on the cemetery’s north side, at that time a section reserved for Whites.

If this is true, Louis R. García died in France fighting for others to have freedoms abroad that he and others like him did not yet enjoy at home.