By Steve Baker, City Historian

What did the schools of Monrovia and an ancient Greek philosopher once have in common? They both made the profound statement, “The foundation of every state is the education of its youth.” These words were first uttered by the fourth century B.C. philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, whose observations on human nature and behavior are as on target today as they were 24 centuries ago. And those words were prominently displayed above the entrance to the 1912 Monrovia City High School main building and later at the main entrance to the 1947 Social Science Building at Monrovia-Arcadia-Duarte High School.

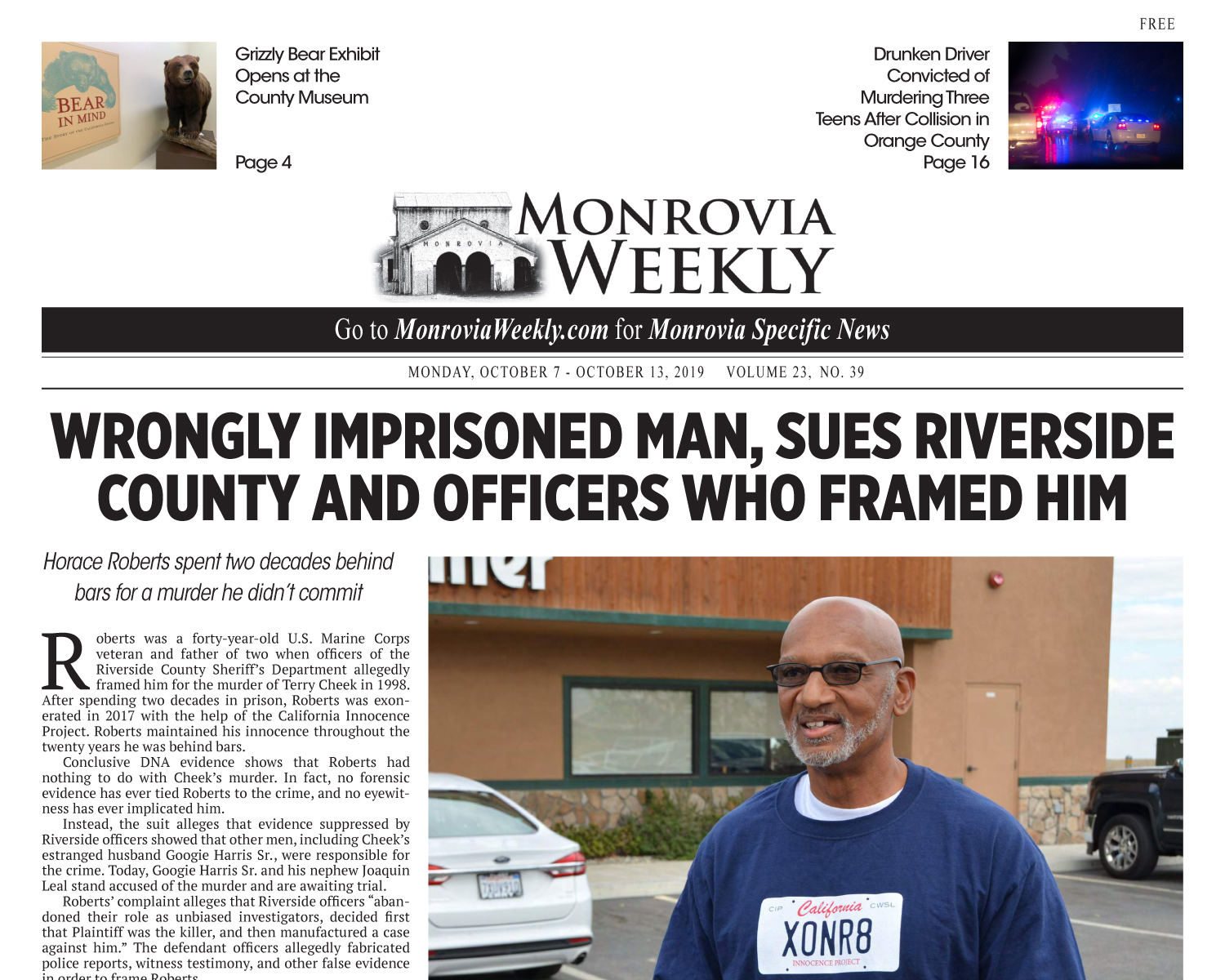

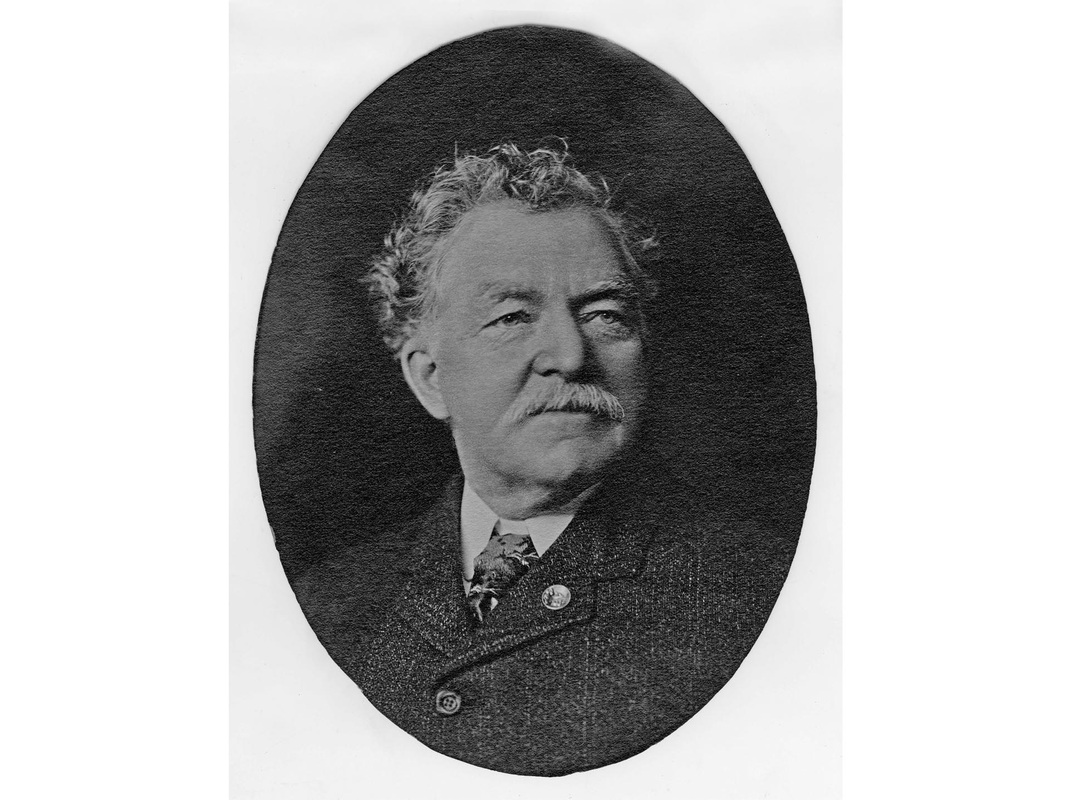

But let’s go back a few years to the beginnings of public education in Monrovia. Monrovia was founded on May 17, 1886 by the Monrovia Land and Water Company and named after William N. Monroe, who settled here with his family in 1884. Monroe needed no introduction to the power of education; he was college educated and had taught school for two years in rural Iowa before enlisting in the Union Army after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. He knew that any new community would be more attractive to potential residents if it offered the benefit of public education. So committed was he to public education that he paid for the first school out of his own pocket!

We are indebted to J. H. Strine, superintendant of schools, for this early history of public education in Monrovia that appeared in his annual report for the year ending June 30, 1898: “The first public school in Monrovia was held in Barnes’ Hall during the school year 1886-7, with Mrs. J. T. Tuttle as teacher. It was supported by W. N. Monroe until the close of the term, May 2, 1887. On May 7 of the same year the County Superintendent appointed W. N. Monroe, E. W. Little, and J. T. Tuttle trustees, and these elected Miss Vesta A. Olmstead teacher for the remainder of the year—May 10 to June 24, 1887. There were, during this time, 54 pupils enrolled. July 7, 1888 the Monrovia City School District was formed, as authorized by the Board of Supervisors. W. C. Badeau, E. P. Large, and U. Zimmerman were elected trustees. Jas. A. Foshay was made principal of the school, and the first term opened Sept. 17, 1888.”

Other early accounts add that the school began in November of 1886 with 12 pupils and one teacher. The location of that first public school still exists—on the second floor of the venerable building at the northeast corner of Lemon and Myrtle avenues.

As the school population increased, it outgrew Barnes’ Hall, making a separate public school building a necessity. The first school building was erected during the summer of 1887 at the southeast corner of Orange and Mayflower avenues, and was named the Orange Avenue School. (Orange Avenue is now known as Colorado Boulevard.) The building was constructed with funds provided through the premium sale of lots in the Bicknell Addition to the Town of Monrovia as well as supplemental funds provided by William Monroe. The two story building contained three classrooms on each floor and a centrally placed bell tower, and was designed in the popular Eastlake Style by local architect Luther R. Blair.

Since the Orange Avenue School provided instruction for eight grades only, there was growing sentiment for the formation of a high school. On July 22, 1893, the electorate of Monrovia approved the formation of the Monrovia City High School District. Classes began that fall in two rooms on the second floor of the Orange Avenue School. Two years later the school had its first graduating class of two students: Carroll Fowler and Ida Whittington, both of whom went on to higher education.

The year 1903 saw the construction of the Ivy Avenue School, located where Clifton Middle School is today. That building was intended for an elementary school, but it ended up as shared space with the high school, since the high school had outgrown its original home at the Orange Avenue School but could not afford its own building. The high school rented space until 1910, when it was able to purchase the site for $50,000 with the proceeds of a bond measure and the location became a high school campus only. The bond measure also made possible what was touted as a polytechnic high school building in a newspaper article published in 1910. The new building, designed by the Los Angeles firm of Allison & Allison, was completed in 1912 and served until 1929 when the high school moved to its present location. And it was that building that bore the quotation from Diogenes.

The southeastern quadrant of Monrovia received a school building in 1907 with the completion of the Charlotte Avenue School, located on what is now Canyon Boulevard. It housed eight grades in a two story brick building of artistic design located on a campus lined with mature pepper trees. The following year a two-room school building was constructed on Linwood Avenue where Vons is today. That building, together with a second building designed to match the first, later served as the headquarters for the Monrovia City School District. And the final school building constructed in the early years of the 20th century, in response to the active growth of Monrovia after 1904, was the Wild Rose Avenue School, completed in 1912.

As it neared its 30th year of service to education in Monrovia, the Orange Avenue School was showing definite signs of wear and tear. Mamie Norene Maag, who served as principal at Orange Avenue from 1915 to 1927, recalled in a 1955 interview how the old building would shake as students rushed up the worn, rutted stairs and how bats from the bell tower would make their way into the classrooms, emerging from behind pictures at inopportune moments. She also recalled how it took three attempts to pass a bond measure to replace the old building with a new one. The old building succumbed to progress in 1917 and was replaced with a building designed by local architect Frank O. Eager. His creation was Native American inspired, and presaged the Aztec Hotel of 1925. After 30 years of service the bell in the tower was retired as well. It spent a 47-year hiatus in the school district warehouse and then was installed in a tower once again—this time at Monrovia High School.

The Roaring Twenties roared in Monrovia as well as nationally. Both Duarte and Arcadia voted to join the Monrovia City High School District, lacking the ability to support high school districts of their own. The elementary school population of Monrovia roared as well, growing to such a degree that two new schools were necessary. In the northern section of Monrovia, houses were replacing orange trees and Mayflower School was placed in service, opening its doors in 1925. And in the southern section of Monrovia, growth was taking place as well. Santa Fe School, named after the adjacent Santa Fe Railroad, opened in 1927. Both new schools housed grades first through eighth.

Also in 1927 two important events took place. On June 14, a successful bond measure in the amount of $625,000 passed, allowing the high school district to purchase a site at Orange Avenue (now Colorado) and Sixth Avenue (now Madison) and to construct the original six buildings on the High School campus. On Dec. 12, 1927 the high school district was re-named the Monrovia-Arcadia-Duarte High School District to reflect the constituent communities. The new campus was ready for occupancy in January of 1929 and was dedicated on Jan. 25 with impressive ceremonies. The Palladian façade of the main building originally bore the names of the three constituent communities, each name in geographical order above one of the three arched entries to the building.

After the high school moved to its new campus, all seventh and eighth grade classes in Monrovia were moved to the former high school campus and it was known as the Ivy Avenue School once again. At about the same time, the name of Charlotte Avenue School was changed to Huntington School.

All was well in Monrovia, structurally speaking, until March 10, 1933 when an early evening earthquake jolted all of Los Angeles County and beyond. Especially hard hit were the public school buildings of Long Beach. The newspapers featured disturbing photographs of heavily damaged schools with fallen ceilings draped across student desks, and there could be no doubt of the disastrous consequences had the earthquake struck earlier in the day when the classrooms were occupied. In response to the damage and the possible death toll, an act (the Field Act) made its way through the California Legislature and was signed into law in perhaps record time. The act provided for stringent seismic safety for all new school buildings and the evaluation of all existing structures.

In due time, the engineers reached Monrovia. Huntington School showed obvious signs of damage and had been vacated as a result of a successful lawsuit filed on behalf of the minority parents whose children had been attending the school. Wild Rose, Ivy Avenue, and Orange Avenue schools did not show signs of damage, but were suspect as they were of unreinforced masonry construction. Ultimately, those schools as well as Charlotte Avenue School were condemned. The high school, as well as Mayflower and Santa Fe Schools, of newer construction, were spared.

It was a huge blow for the Monrovia City School District and it took several years, in the midst of the Great Depression, to raise the funds to either replace entirely or to extensively renovate the condemned buildings. New schools, in the streamline moderne style, were completed by 1937. Orange Avenue School was renamed Monroe School to honor William Monroe, who had been so instrumental in establishing public school education in Monrovia. Ivy Avenue School was renamed Clifton School to honor Archie R. Clifton, former teacher and principal at Monrovia High School who went on to become superintendent of schools for Monrovia as well as Los Angeles County.

The post World War II boom in Southern California impacted the school population of Monrovia and the adjacent communities as well. Arcadia was able to successfully create its own high school district in 1951, and the local high school became known as Monrovia-Duarte High School. The following year, 1952, Plymouth School was placed in service to serve the student population in the southern end of the Monrovia City School District. By 1957, Duarte was able to support its own high school district. Before the separation took place, the combined district built Duarte High School and students began attending early in 1958. In 1958 Bradoaks School was placed in service to serve the student population in the eastern portion of Monrovia as orange trees gave way to houses and Wild Rose was bursting at the seams.

The year 1960 marked the end of two venerable institutions: The Monrovia City School District of 1888 and the Monrovia City High School District of 1893. The voters of the two districts voted to combine the two into the Monrovia Unified School District. Monrovia High School had gone full circle and was known once again by its original name.

The original buildings at Mayflower and Santa Fe, survivors of the Field Act, succumbed in 1966 to increased concerns about seismic safety and were replaced. Four years later, to voluntarily deal with the de facto segregation that existed in Monrovia schools, the school district was reconfigured. Huntington School, essentially a segregated facility, was closed and the student population was assigned to other schools. Clifton became a middle school with grades six, seven, and eight, and Santa Fe became a second middle school instead of an elementary school.

Since that time, Canyon Oaks High School and Mountain Park School have been added as alternatives to Monrovia High School. Further changes include the designation of Santa Fe as Santa Fe Computer Magnet School and Wild Rose as Wild Rose School of Creative Arts. The Monrovia Community Adult School has a history going back decades and the Canyon Early Learning Center was created more recently on the former Huntington School campus. The schools of Monrovia began with William Monroe, and they continue with limitless possibilities. Who could ask for more?